Article de Ekin Kececioglu Aytemiz (MS EnvIM 2023-24)

Introduction

Either affected by climate change-induced events or just being part of higher intellectual pursuits on the future of our planet, most of us develop an understanding of environmental concerns and climate change, and we would like to adapt our choices to the information of the real situation in favor of a more sustainable environment. On the other hand, we usually get the actual results of our actions in the long run.

Meanwhile, what keeps us on the road, convinces us to proceed accordingly as individuals, and supports our decisions towards sustainability intrinsically? How do we evaluate a certain type of action as “pro-environmental” or “sustainable” and decide to invest our time and enthusiasm in displaying it?

How can the notion of emotions and affects be used in shaping decisions within an economic context? Could pro-environmental behaviors and approaches be exempt from this? More importantly, how can policy policymakers or planners induce pro-environmental behaviors without creating a sense of limiting the choices?

“Eat the big frog first!” – What if I do not know which one is the big ?

The increasing attention to the “self-care” concept in public as well as the focus on productivity and time management practices in the business promoted certain approaches to be acquired by practitioners of these techniques, and they usually make them more understandable with the help of certain metaphors. “Eat the big frog” is one of these, and it aims to underline a strategy to boost productivity. (Laoyan, 2025)

As a part of this recommendation, it is suggested to assess and prioritize big and daunting tasks in your To-Do list and fulfill them as “first thing first” to get more sense of accomplishment at the beginning and save your precious motivation for the rest of your day.

Surprisingly, when it comes to adopting more sustainable behaviors, an interesting finding recently came from the front of behavioral science. It has been observed that people might not be always good at identifying “big frogs” which implies in this case the behaviors that have more potential in reducing carbon emissions as a primary way of climate change mitigation. According to a study involving 500 participants in the US, low-impact behaviors are adopted at a higher rate than high-impact behaviors and finally, they induce more positive emotions than the latter ones. (Asutay, 2023)

In the study concerned, the participants answered a survey presenting a list of behaviors in different domains including food, transport, energy use, housing, and choices in consumption (will be called “mitigation behaviors” below).

The participants assessed how they perceive the impacts of these mitigation behaviors in the reduction of carbon emissions and their liking for these behaviors (both are on a scale from very negative=1 to very positive=5). It has also been questioned how difficult it might be to adopt these behaviors and whether the participants are performing any of them. The average potentials of these mitigation behaviors were listed as “tons CO2 equivalents per capita per year (tCO2/ca/yr)” based on previous literature data (Ivanova et al. 2020) and these values were taken as the “actual” impacts for the purpose of this study.

Once the assessment results were compared with the actual mitigation potentials of these behaviors, it was identified that people tend to perceive the behaviors that they like as “more impactful” in reducing carbon emissions and they are more likely to adopt these while most of these behaviors are in the low-impact category in terms of actual effects in reduction of carbon emissions. For example, the behaviors like recycling, composting or using less paper induced a more positive effect on the participants (3.9 – 4.5 out of 5.00, Recycling has the highest affect score of 4.5 among all proposed behaviors). Similarly, these have been adopted more and assigned as quite impactful (3.1 to 3.8 out of 5) while their actual impacts are around 0.01-0.06 tCO2/ca/yr.

On the other hand, mitigation behaviors with relatively high potential like reducing living space (0.34 tCO2/ca/yr) or living car-free (2.10 tCO2/ca/yr) were considered less impactful than the above-listed actions (perceived impact scores are 3.94 and 2.56) and were found less positive (with affect score of 2.69 and 2.56, respectively).

Considering the above findings, at least at the level of the target group of this presented study, it can be mentioned that individuals may neglect the actual impacts of sustainable behaviors both in assessing and adopting them. Instead, they probably lean towards the actions that give them a sense of accomplishment and positive emotions. Of course, people preferring easy and more positive tasks can be tolerated as long as no one has been harmed. From another point of view, it may seem “unproductive”, or even “irrational” to choose a low-impact action instead of doing more. But is this an event-based psychological observation at the individual level or is there a way of expressing it in a broader and social context ?

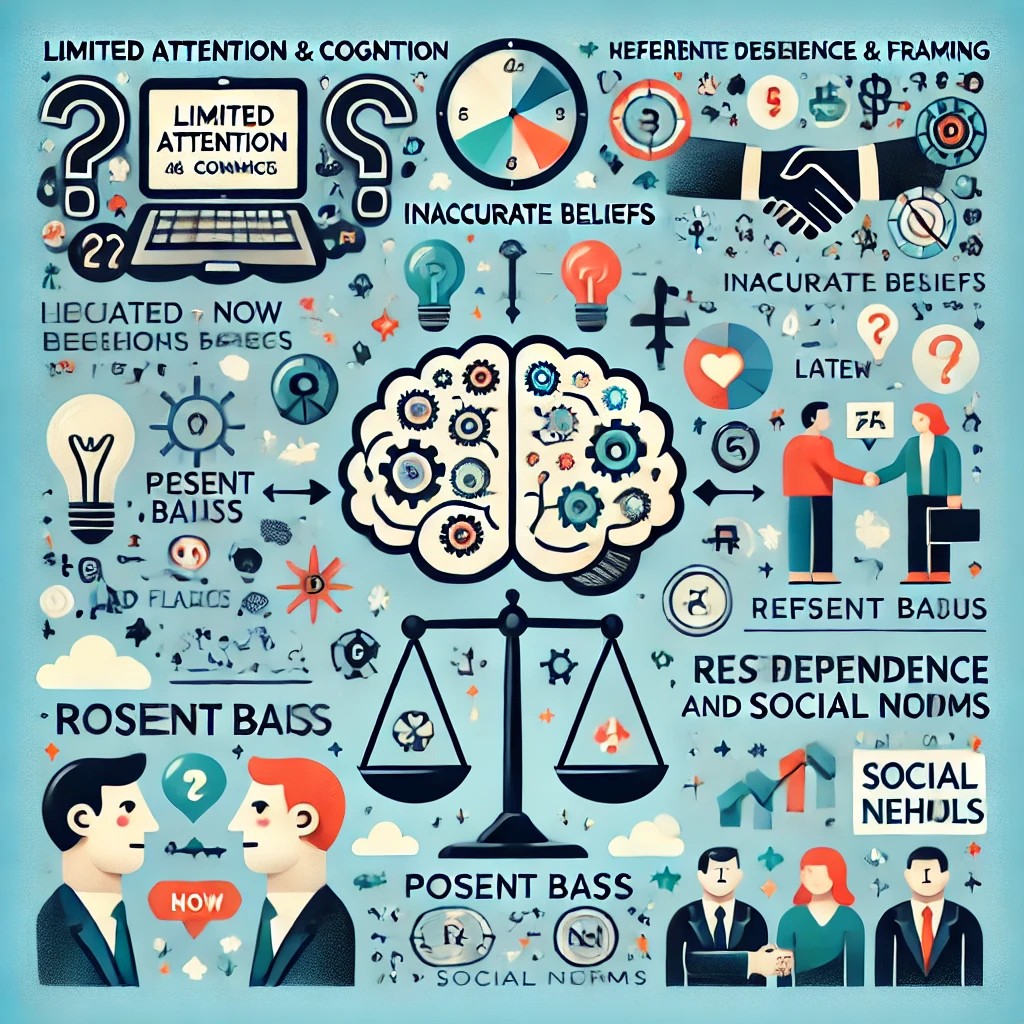

Being open to contributions from many disciplines including sociology, psychology, and anthropology, “behavioral economics” can be described as “an approach to understanding human behavior and decision-making that integrates knowledge from psychology and other behavioral fields with economic analysis”. (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2023).

In the initiation era of behavioral economics, the researchers presented key arguments based on observation of the traditional economy framework which accepts, in contrast, human decision-making taken as a rational process by default until then. (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979; Simon, 1955; Thaler, 1980). These arguments prepared the basis of core principles of this field and highlight several important peculiarities of the human decision-making process as follows:

- Limited Attention and Cognition: People have limited ability to focus on and process information, leading to errors even in simple decisions.

- Inaccurate Beliefs : Individuals often misunderstand situations, incentives, or their own abilities due to limited attention and cognition.

- Present Bias : People prioritize immediate concerns over future consequences, affecting decisions about spending, saving, and utility.

- Reference Dependence and Framing : Decisions are influenced by comparisons to a reference point (like the status quo) and how options are presented.

- Social Preferences and Social Norms : People care about their social standing, compare themselves to others, and seek to align with societal expectations.

When it comes to measures and action on climate change, there is a considerable disadvantage for individuals to concentrate on the outcomes of their choices as the effects are observed in the long run. This fact, unfortunately, feeds the sense of uncertainty on the precise effects, and it becomes harder for individuals to be accurate for day-to-day decisions based on probabilities even under the influence of livelihoods, their current homes and possessions, and long-standing habits and beliefs.

While considered narrow initially, the behavioral economy became a major subfield of the economy and combines the strong theoretical framework of the main discipline with an applied perspective. Behavioral economists explore new ways to apply knowledge of human behavior in designing many areas and tools like interventions to encourage people to make beneficial choices that, for example, encourage actions to protect the environment.

These intervention strategies which are also referred to as “nudge” are usually low-cost and target to alter the choice architecture in many ways like facilitating, framing, using the influence of social norms, and many others. (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2023)

![Figure 1. [Categorization of nudging strategies]. Adapted from the NUDGE project (NUDGE Project, n.d.).](https://blog-isige.minesparis.psl.eu/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/Image3.jpg)

To be more result-oriented, identified strategies can be coupled with the concern to be addressed. It can be addressed to the public or relevant target groups (for example, consumers preferring more carbon-intensive services like aviation, fossil fuel for heating or energy). The alternatives might be presenting the behavior to be promoted as the “default” option or supplying key information about the pro-environmental behavior more prominently to ease the decision-making process without permitting decision fatigue or biases to work on.

A few examples might help to make the subject more understandable and see practical aspects of the design and implementation of nudges. Meatless Monday action serves as a clear example of a nudge within behavioral economics, as it subtly encourages individuals to reduce meat consumption without restricting their freedom of choice. As the name implies, each Monday, the participants choose to prepare all their meals or a selected course (like lunch or dinner) with only plant-based ingredients. They share visuals of their meals, preparation process or even recipes on social media to encourage each other.

By leveraging the principle of choice architecture, this action designates one specific day for plant-based eating, simplifying decision-making for those who might find a full dietary shift overwhelming. The initiative is voluntary, relying on framing and social norms to encourage participation, as branding it as a collective movement fosters a sense of community and shared purpose.

Additionally, Meatless Monday emphasizes positive outcomes, such as improved health and environmental sustainability, making the choice more appealing without guilt-tripping participants. Its success lies in its salience (tying it to a memorable day), the small commitment it requires (just one day a week), and its non-intrusive design, which allows individuals to feel in control. Over time, this manageable approach can contribute to incremental habit changes, aligning individual behaviors with broader societal goals like reducing carbon emissions and conserving resources.

Another example can be given of energy efficiency with a more elaborate methodology.

Within the frame of a Horizon-Europe project titled “NUDGE – Nudging consumers towards energy efficiency through behavioral science”, five pilot studies of energy efficiency in five different EU countries (Belgium, Greece, Germany, Portugal, and Croatia) have been conducted to describe behavioral interventions complementing the existing monetary or in-kind incentives and prepare a policy toolbox for further actions in this field.

![Figure 2. [Infographic of pilot studies in the frame of NUDGE project]. Adapted from the NUDGE project (NUDGE Project, n.d.).](https://blog-isige.minesparis.psl.eu/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/Image4.jpg)

Examples of the techniques preferred to deliver the messages are as follows :

![Figure 3. [Nudging strategies used in the pilot studies in the frame of NUDGE project]. Adapted from the NUDGE project (NUDGE Project, n.d.).](https://blog-isige.minesparis.psl.eu/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/Image5.jpg)

In Croatia, the pilot study aimed to raise energy awareness by providing smart meter data, to inform participants which are also part of solar PV cooperative members about their contributions and to promote this shared solar power system which would enable more consistent and economic renewable electricity supply for the communities. However, a policy reclassifying households as renewable traders if they produced excess electricity (with respect to their consumption) led nearly half of participants to limit their solar output. Smart meter data showed reduced production or increased consumption as the year-end deadline neared. This unintended externality brought inconsistent results and undermined the nudges in this case, highlighting how similar efforts can be affected by broader regulatory contexts.

Considering the anthropogenic nature of climate change and the financial scale of the much-needed interventions to cope with and adapt to it at the same time, it is highly expected that the research in behavioral economics can be more easily converted into action. However, studies involving some trials of possible “nudges” still show context or target group-dependent results and could not overcome beliefs and presuppositions despite the benefits of the desired/preferred actions for the individuals and the environment.

For example, the interventions on decreasing household energy use may provide many promising results with the increases in market prices for energy. In contrast, the ones for encourage the usage of public transportation may still be facing a certain level of hesitation in target groups since traveling with their private car may signify some sort of “autonomy” or “security” for certain individuals.

Again, a successful strategy to promote public transport in the urban context, equipped with many alternatives like bus, subway, tram, maritime transport, may not grasp easily the citizens living in rural areas. In these sections, public transport services might be impaired with certain externalities like the limited number of destinations available, time spent on public transport or issues with punctuality. This implies how important effective planning of interventions and a close follow-up by the policymakers eventually is and even context-dependent fine-tuning of approaches.

Conclusion

Emotional processes and the complexity of human decision-making play an important role in assessing the impact of our behaviors and adopting more impactful behaviors for the environment and climate change.

Some examples of nudging practices are criticized by behavioral psychologists as they are mostly built on strategies and assumptions in a particular case. They may sometimes lack a theoretical framework that combines behavioral science and environmental psychology resulting in a neglect of the role of emotions in human decision-making. This causes some concerns about using the same intervention once again, understanding the underlying mechanisms, or adapting in another context.

A reciprocal reservation is also expressed in the behavioral economy side for the work performed in the role of affect and emotions in human decision-making as well. The main argument is that the studies are usually performed with participants from highly emitting countries and emotional positions towards things to be done to mitigate climate change and climate-induced risks and may differ in different test groups in different countries.

Our search for the “ideal” behavior to show much-needed respect for our planet is turning into a spiral with the intriguing nature of our decision-making and the complexity of our modern world. This spiral will only steer us in the right direction if we strive to better understand ourselves, what we choose, and why we choose it, considering all our differences and inequalities we are coping with.

References:

- Amiri, B., Jafarian, A., & Abdi, Z. (2024). Nudging towards sustainability: A comprehensive review of behavioral approaches to eco-friendly choice. Discover Sustainability, 5(1), 444. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43621-024-00618-3

- Asutay, E., Karlsson, H., & Västfjäll, D. (2023). Affective responses drive the impact neglect in sustainable behavior. iScience, 26(11), 108280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2023.108280

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263–291. https://doi.org/10.2307/1914185

- Ivanova, D., Barrett, J., Wiedenhofer, D., Macura, B., Callaghan, M., and Creutzig, F. (2020). Quantifying the potential for climate change mitigation of consumption options. Res. Lett. 15, 093001. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ab8589

- Laoyan, S. (2025). Why you should eat the frog first. Retrieved January 7, 2025, from https://asana.com/resources/eat-the-frog#does-eating-the-frog-work

- Monday Campaigns. (n.d.). Meatless Monday. Retrieved January 7, 2025, from https://www.mondaycampaigns.org/meatless-monday

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2023). Behavioral economics: Policy impact and future directions. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/26874

- NUDGE Project. (n.d.). The NUDGE project. Retrieved January 7, 2025, from https://www.nudgeproject.eu/

- Simon, H. A. (1955). A behavioral model of rational choice. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 69(1), 99–118. https://doi.org/10.2307/1884852

- Thaler, R. H. (1980). Toward a positive theory of consumer choice. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 1(1), 39–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-2681(80)90051-7