Article de Cordélia de Chambure (MS EnvIM 2023-24)

Introduction

From the 2019 manifesto for ecological awakening signed by 30,000 students to the bold speeches of AgroParisTech graduates in 2022, young voices are calling for transformative changes to address urgent environmental and social crises. Two approaches are often considered : an individual lifestyle shift (such as adopting a rural, self-sufficient lifestyle) or a broader, systemic change in the way we work and produce.

This collective shift raises important questions : what activities are worth dedicating our lives to ? Why is the organization of work central to addressing environmental and social issues ? What challenges must we overcome to achieve joyful, sustainable growth ?

Why change the nature of work to address environmental and social crises?

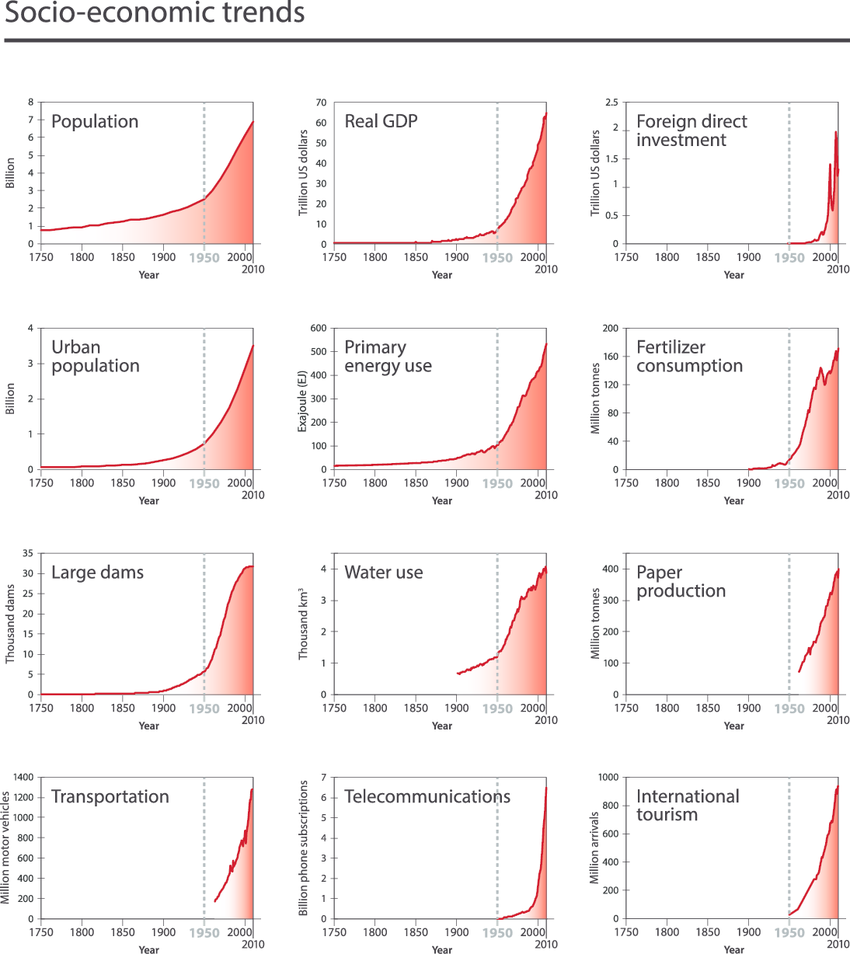

The current production system is not sustainable, as evidenced by the “Limits to Growth” report in 1972. All productive activities rely on using natural resources (use of lands, water, raw materials …), causing harm and pollution to the environment.

Work involves both creating products and depleting resources. However, not all work is inherently unsustainable. Historical practices like agroecology, which integrates local biodiversity into farming systems, show how production can align with environmental regeneration.

To respect planetary boundaries², we need to embrace degrowth³, a concept that goes beyond reducing emissions. Degrowth addresses biodiversity loss, resource depletion, and pollution, all symptoms of an unsustainable economic model. As Timothée Parrique suggests, degrowth is not simply a critique of growth but a trajectory, emphasizing the redistribution of resources and redefining societal goals toward well-being.

Economic growth relies on traditional drivers : labor, capital, and technology (the Solow residual⁴ which policies have little direct influence on as it is considered exogenous). According to economist Robert Solow⁵, these three factors explain how economies expand. However, the focus of policies on these drivers often neglects their environmental and social consequences. This article examines how the organization of labor and capital contributes to these challenges

Thanks to technological progress, productivity gains have considerably increased production during the 20th century. Although overall working hours per person have decreased compared to the 19th century, the expected reduction in working hours has not matched productivity gains and the quality of production has decreased. Instead of using these gains to free up time, we have chosen to produce and consume more, intensifying environmental impact.

GDP growth often harms both the environment and social well-being. According to Heller, Gorz, and Marx, the capitalist economy creates artificial needs instead of meeting authentic ones, aligning demand with what can be supplied rather than vice versa (Gorz, 1980). This aligns with the Easterlin Paradox (which shows that higher income doesn’t always lead to greater happiness after basic needs are met).

GDP-driven growth can worsen inequality. UN Special Rapporteur Olivier De Schutter highlights that it often benefits the wealthy more than the poor, exacerbating inequality and environmental harm. His 2024 report calls for policies that prioritize human rights and sustainability over economic expansion.

Our current way of producing is therefore neither sustainable for planetary resources nor socially sustainable.

What are the main barriers in the world of work to achieve a desirable and joyful degrowth?

Historically, work was not as central or intensive as it is today. Before industrialization, work followed natural rhythms and was often irregular. The rise of the clock and time discipline, symbolized by Benjamin Franklin’s “time is money” (emphasizing the need to conscientiously “save” or “spend” every minute one possesses) fundamentally changed our perception of labor.

Our current conception of work is partly based on the works of Adam Smith and classical economists in the 18th century. They emphasized “productive work” that generated economic value, marginalizing other activities like caregiving or volunteer work. This focus on commodification laid the foundation for capitalism.

The question of what constitutes useful⁶ work for the society and how is it valued became especially pressing during the COVID-19 pandemic with the importance of “essential workers”.

Work itself is useful because it plays a socially integrative role, providing individuals with purpose, structure, and a sense of belonging, as discussed by Émile Durkheim in his theories of social cohesion (The Division of Labor in Society, 1893). Additionally, sociologist Robert Castel emphasized that work serves as a pillar of social stability and identity (Les métamorphoses de la question sociale, 1995).

However, for work to fulfill its integrative function, it must avoid creating social inequalities or depleting natural resources.

It is not suggested that all work must have a direct ‘purpose’ but it should avoid detracting from societal well-being by harming the environment or increasing inequality.

Our society often attributes value based on economic profit rather than true social utility. For example, a trader might earn far more than a nurse, even though healthcare workers are critical to our well-being. This discrepancy highlights the misalignment between economic reward and societal and how value and utility are attributed in our economy.

This same focus on profit influences how we consume. In a consumption-driven society, the emphasis on exchange value—what something is worth in the market—often overshadows its use value, or how much it truly benefits us. For instance, while a new iPhone may offer only marginal improvements over an older model, it has a significantly higher exchange value simply because it is new. Such prioritization of exchange value over practical utility shapes both our work lives and our free time, where we often consume services like meal deliveries or cleaning to save time—usually for further consumption.

This cycle includes compensatory spending, where people buy goods to alleviate work-related stress or reward career success. These patterns fuel what we might call ‘work-induced work,’ where increased consumption leads to additional production with further environmental consequences.

Moreover, studies from organizations such as the Stockholm Environment Institute and Oxfam⁷ (2023) highlight the link between income and environmental footprint: as income increases, so do spending and consumption, which place further pressure on ecological systems. Factors such as time scarcity, advertising, accessible credit, and global supply chains reinforce this cycle of work, income, and consumption, embedding consumption deeply in society. Despite being widespread, this focus on consumption deserves closer examination because it promotes values and behaviors that are unsustainable.

How to move towards a simpler society by changing the world of work?

To reduce overall production and consumption, we should change indicators and myths. We should, rethink a society that fears wasting time, venerates hard work, productivity, efficiency and consider embracing peaceful unproductiveness, such as laziness. This philosophy is well described in Hadrien Klent’s latest novel Paresse pour tous (“Laziness for Everyone”).

To foster a society focused on well-being rather than productivity, it is essential to prioritize indicators such as Gross National Happiness Index proposed by the king of Bhutan (the first country in the world to have a negative carbon footprint) or Sustainable Development Index (SDI), which provide more holistic measures of societal health.

From the perspective of GDP, a traffic jam might seem beneficial due to increased fuel consumption, which contributes to economic growth. However, this completely disregards the negative impact on well-being, such as stress, lost time, and environmental harm. This example highlights how GDP often misrepresents societal welfare, focusing on economic activity over human and environmental health.

Restructuring work organization

One crucial measure would be sharing working hours to help reduce unemployment and pressures on the environment and to improve working conditions. It would also promote various activities outside of work, establish and reinforce different priorities, and enable new life experiences across a range of time frames. However, this sharing should be coupled with systemic reorganization to avoid creating two unproductive jobs (Cf Bullshit jobs by David Graeber) instead of one.

Also, concrete policies and accompanying measures should be carefully designed and framed to counteract rebound effects and other undesired consequences. Reducing working hours typically leads to lower income, which would be better for the environment. However, this may pose challenges for low-income individuals.

Research suggests that reducing work hours and incomes for high earners has greater environmental benefits (Neubert, Bader, Hanbury, Moser, 2022). To address these challenges, reducing incomes should be complemented by redistributive policies that ensure equitable access to essential needs.

One potential approach is to introduce universal access to basic services such as housing, food, and transportation, which could alleviate reliance on cash income while ensuring everyone has access to necessities. Simultaneously, incomes, particularly those of high earners, could be moderately reduced alongside measures like progressive taxation on wealth, property, or high-carbon activities. Policies that establish income floors and caps within companies, along with tax incentives for organizations that promote fair wage practices, could further support equity. These measures must be part of a participatory and transparent framework to secure public trust and successful implementation.

This reduction would enable a better life balance (leisure, family, friends). It would also liberate time for postwork alternatives such as autonomy (cooperatives, associations, commoning (Bollier, 2015)) and allow citizens to dedicate time to politics. Indeed, citizen involvement is necessary, especially for environmental issues, which are largely at the local level.

Citizen engagement is also imperative on the private sector. Democratizing work, as proposed by Dominique Méda, can empower employees and foster innovation. This involves actions such as promoting employee participation in decision-making, establishing workplace forums for open dialogue, and transitioning towards cooperative models for greater autonomy and control over work processes.

Production change

Transitioning back to local craftsmanship, recycling and second market where feasible to prioritize quality over mass production is an essential step. This shift would not only reduce overall production but also alleviate resource demands, decrease transportation needs, lower energy consumption, and mitigate overconsumption.

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought into focus the issue of essential commerce, sparking a crucial discussion about what to prioritize in production. These ongoing debates should question the validity of certain roles : just because a job exists doesn’t automatically make it legitimate. Indeed, it’s worth considering the societal and environmental impact of positions e.g. in advertising or tax optimization.

Redirecting resources from redundant positions toward more meaningful employment is crucial for fostering a sustainable economy. It is important to prioritize eco-friendly tasks such as maintenance and recycling. Additionally, reviving pre-World War II practices of self-production, particularly in food systems, could play a vital role in creating resilient communities.

Conclusion

To conclude, sustainable postwork alternatives are available, meaningful, and desirable. As discussions about work and its societal impacts continue, especially among younger generations, it’s clear that change is both necessary and possible. However, there are still barriers to overcome, rooted in societal norms and structures.

Recognizing the unsustainability of our current world, is imperative to explore alternatives. While this article offers one perspective, there are countless ways to envision a more desirable and sustainable future. Whatever the ways, de-growth is part of the solution for creating equitable and resilient societies. Many topics must be addressed to go from utopia to reality.

Let us move forward with imagination and determination to build a world where well-being, rather than profit, is our ultimate measure of success.

“The more clearly we can focus our attention on the wonders and realities of the universe about us, the less taste we shall have for destruction.” Rachel Carson, The Sense of Wonder

Sources

¹ Steffen, Will & Broadgate, Wendy & Deutsch, Lisa & Gaffney, Owen & Ludwig, Cornelia. (2015). The Trajectory of the Anthropocene: The Great Acceleration. The Anthropocene Review. 10.1177/2053019614564785.

² Planetary boundaries are ecological limits within which humanity can safely operate to prevent destabilizing Earth’s systems, covering areas like climate and biodiversity (Rockström et al., 2009; Steffen et al., 2015).

³ The term “degrowth” in this article is understood as an “alternative to growth with the aim of respecting planetary boundaries” and is therefore not synonymous with recession. This is why we talk about desirable and joyful form of degrowth.

⁴ Solow residual represents the unexplained portion of economic growth attributed to factors beyond traditional inputs like labor and capital accumulation, often seen as a measure of technological progress or efficiency gains. Solow, Robert M. “Technical Change and the Aggregate Production Function.” The Review of Economics and Statistics, vol. 39, no. 3, 1957, pp. 312-320 (seminal paper by Solow introducing Solow’s residual concept).

⁵ Robert M. Solow, “A Contribution to the Theory of Economic Growth,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 70, No. 1 (Feb., 1956), pp. 65-94.

⁶ For this discussion, utility will be defined as maximizing social well-being with minimal environmental impact.

⁷ https://policy-practice.oxfam.org/resources/climate-equality-a-planet-for-the-99-621551/

Bibliography

- André Gorz. (1990). Bâtir la civilisation du temps libéré. Les liens qui libèrent

- Céline Marty. (2021). Travailler moins pour vivre mieux. Dunod

- David Graeber. (2018). Bullshit jobs. Simon & Schuster

- Guide pour une philosophie antiproductiviste Héloïse Leussier. (2024). Les vertus écologiques de la baisse du temps de travail. Reporterre

- Hadrien Klent. (2021). Paresse pour tous. Babelio

- Jason Hickel. (2020). Less Is More: How Degrowth Will Save the World.

- Maja Hoffmann. (2017). Change put to work : A degrowth perspective on unsustainable work, postwork alternatives and politics. Lund University Centre for Sustainability Studies

- Neubert, Bader, Hanbury, Moser. (2022). Free days for future? Longitudinal effects of working time reductions on individual well-being and environmental behaviour. Elsevier

- Razmig Keucheyan. (2019). Besoins artificiels. La Découverte

- Stockholm Environment Institute and Oxfam. (2023). Climate Equality : A planet for the 99%

- Socialter Magazine. (2024). Décroissance : réinventer l’abondance. Hors-série n°18.

- Timothée Parrique. (2022). Ralentir ou périr : l’économie de la décroissance. Seuil.