Article de Camille Dousset (EnvIM 2021)

Introduction

Although in 2016, a survey showed that 97% of climate scientists agree that climate change is caused by humans (Michigan Technological University, 2016) and that the latest IPCC report (IPCC, 2022) warns on the urgency and irreversibility of the situation if no action is taken, the fight against climate change remains largely below current concerns. Indeed, on a global scale, climate change does not appear among the 5 main concerns of the populations (Ipsos, 2022). Inflation is first, followed by poverty and social inequality, unemployment and employability, crime and violence, corruption and finally the Coronavirus.

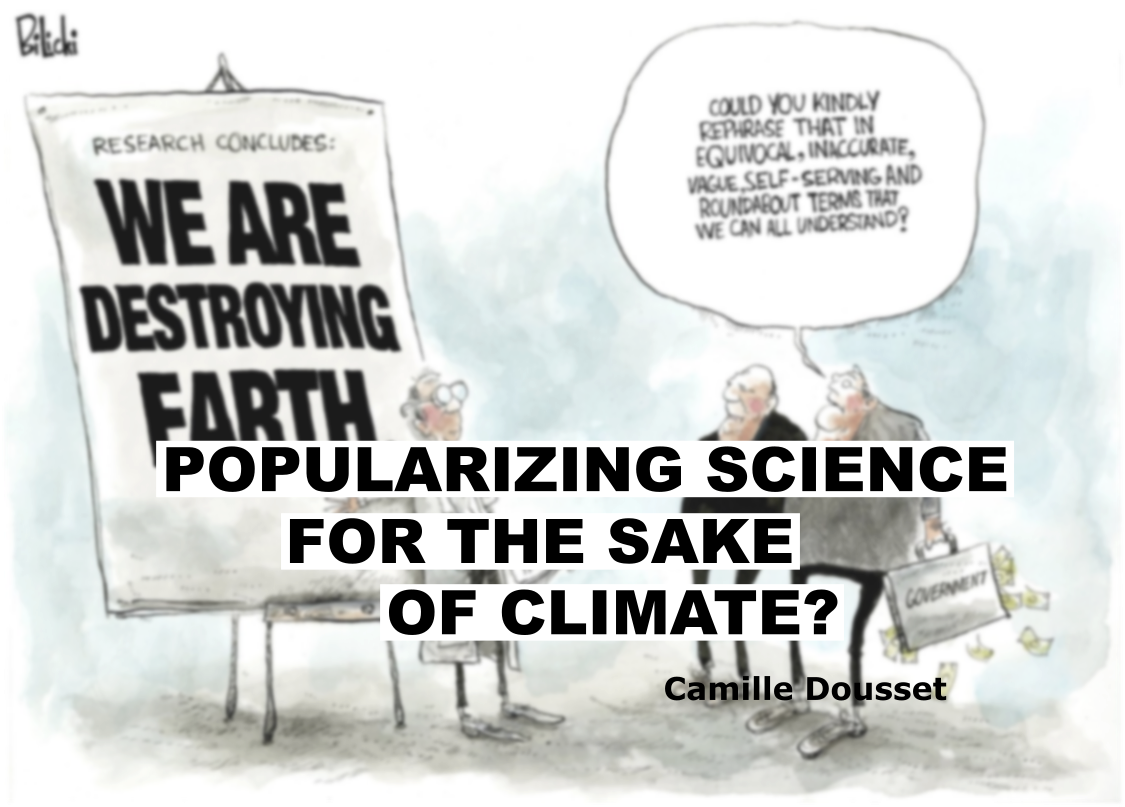

This gap highlights the immense challenge of effective environmental communication for the general public; and in particular the importance of democratizing scientific discourse. How to explain that, despite irrefutable scientific conclusions, the scientific discourse is still largely inaudible? Inaudible because it would be insufficiently clear or because what it conveys is too disturbing? We cannot make any conclusion, yet this problem raises the issue of scientific popularization and the need for intermediaries and/or strategies to convince the general public of the emergency linked to climate change.

In a similar situation as the pill dilemma between the red pill and the blue pill in Matrix, when faced with a potentially disturbing truth, the vast majority of people would prefer to remain in ignorance than to take a proactive approach to understand the phenomenon.

So, how can environmental scientists and intermediaries play a role in ending the wait-and-see attitude? To what extent does the popularization of science help climate understanding? On what conditions can it be an ally in the fight against climate change?

What is scientific popularization?

Cambridge dictionary (2022) would define popularization as “the act of making something known and understood by ordinary people.” Scharrer, Rupieper, Stadtler and Bromme (2016) define science popularization as “the important task of making scientific knowledge understandable and accessible for the lay public” (p.1). It is important to highlight that in English “popularization” is used instead of “vulgarization” (“vulgarisation” in French – Ed.). The use of “popularization” is less pejorative than “vulgarization” (Bensaude-Vincent, 2010). Indeed, the term associated with vulgarity would give the impression of a depreciation of the knowledge transmitted (Bouchez, 2018). This term would also imply, according to Bouchez (2018), that science would have a dimension too noble to be transmitted to the general public. Therefore, nowadays, in the different European languages, the terms “mediation” and “communication” of science are consecrated (Bensaude-Vincent, 2010).

For the sake of this paper, the term “scientific popularization” will be used. Beyond the battles of semantics, our concern here is above all about pedagogy, the way of delivering didactic messages adapted to different audiences (Bouchez, 2018).

But, how did we come to develop science popularization? The popularization of science has progressively been built as a bridge between science and society. Indeed, it has intervened to explain certain events. As Jerome (1986) showed, environmental and health scandals such as Chernobyl or Three Mile Island have imposed mediation, due to their scale and impact. Popularization was one of the means of “compensation” towards the society. It has emerged to rebalance power through access to knowledge.

A brief history of science popularization

The history of science popularization can be broken down into three main periods: popular science in the 19th century, popularization in the 20th century and citizen science movements in the early 21st century (Bensaude-Vincent, 2010).

Thus, the popularization appears and develops in a context where the gap between scientists and the public widened considerably. René Sudre speaks of a simple difference of language in the 19th century and then of a difference of world in the 20th century. Indeed, scientific progress is so important in the 20th century, that making quantum physics intelligible is no longer simply a matter of translation between the language used by the world of scientists to the world of common sense (Bensaude-Vincent, 2010).

The authors emphasize this gap: “On one side, therefore, we find producers of knowledge and, on the other, a public defined negatively by the lack of science rather than by its qualities, or even its concerns, or interests (deficit model)” (Bensaude-Vincent, 2010, p.6)

Indeed, in the 20th century, in a state of a growing gap between the lay public and scientists, two tendencies opposed each other. On the one hand, popularizers appeared to try to reduce this phenomenon. The mediator speaks in the name of science and translates the expert language to the lay public, in a one-way diffusion, without exchange. On the other hand, some advocate a diffusion of science in its raw form and not simplified, to fight against the ignorance of the public and to reinforce the social acceptability of scientific discourse (Bensaude-Vincent, 2010).

The philosopher Hannah Arendt accuses scientists of being responsible for this gap, because they would have decided to emancipate themselves from the common world by using an expert language, even “esoteric”. It is following her position that the magazine Science for the people was created in the United States and in the United Kingdom, by other scientists. (Bensaude-Vincent, 2010)

Researchers Thion Soriano-Molla and Rodriguez Moranta (2015) synthetically explain the popularization of scientific knowledge as the result of five factors:

- It is a political issue;

- Experts have made popularization their profession;

- Science, for countries with advanced technologies, has a recreational dimension;

- Science is present in all primary and secondary school reforms;

- We can observe an evolution of our relationship to science in the 21st century with scientists deciding to address the general public.

But, why is this phenomenon of popularization important in the light of climate change? What is at stake in the popularization of scientific knowledge to understand this upheaval? What is its precise responsibility?

Why is it important to popularize the scientific discourse around climate issues?

First, it is important to note that climate change is an extremely complex phenomenon. Climate change is, according to Morton (2013), the most critical “hyperobject.” That is, there are not a multitude of distinct environmental issues, but one environmental issue with multiple manifestations. This is what requires a comprehensive understanding and rigorous treatment of this topic.

One of the manifestations of the relative low level of mainstreaming of the topic is mirrored by the limited presence of the topic in the mediatic mainstream sphere. This was demonstrated during the last debate between the two rounds of the French presidential election, during which climate issues were only discussed for 18 minutes out of the almost 3 hours of debate. What is more, these 18 minutes almost exclusively concerned electricity (Prados, 2022). And this environmental communication is at an urgent state as it takes place in a context where “awareness of this issue is still low in many developed countries and structuring actions in terms of reducing greenhouse gas emissions are struggling to be implemented” (Bouchez, 2018, p.15).

Being an issue of species survival, climate change knowledge cannot be limited to some privileged and highly-educated individuals; it is a collective and global stake.

Besides, it can be seen as a democratic issue. Indeed, popularization would be the means to reduce the gap between science and society; it would be one of the means to give the keys of understanding to the citizens, necessary to make informed decisions. The contribution to limit the effects of climate change has to be endorsed by all stakeholders, meaning we need to make knowledge accessible by the greater number of people. According to Scharrer, Rupieper, Stadtler and Bromme (2016), based on empirical studies, the added value of popularization would be to confirm the lay public in its beliefs after being exposed to popularized content: “laypeople agreed more with the knowledge claims they contained and were more confident in their claim judgments than after reading articles addressed to expert audiences.” (p.1)

This is exactly what happened with the Citizen’s Climate Convention in France in 2019. The 150 citizens, selected to be representative of the French population, had widely varying levels of expertise on the topics under discussion. Therefore, many experts, including climatologists Jean Jouzel and Valérie Masson-Delmotte, were called upon to intervene in order to train citizens on climate issues. The Convention was built as a discussion between the citizen and the experts in order to ease the appropriation of the topics. The results of this citizen experiment are striking. Indeed, after being sensitised and trained on these different subjects, they came up with more ambitious proposals than what had been previously planned by the government (Pouliquen, 2020).

This example clearly demonstrates the power of pedagogy and the democratic stake of scientific popularization. Informing can really shake the status quo and the convictions of everyone.

Training peopleon climate change: what types of popularization?

The scientific consensus has happened (IPCC, 2022). But how to activate change and raise awareness? To understand what type of scientific popularization would be effective for the climate, there are two dimensions to take into account:

1. Which popularizers?

According to Lascoumes (2002), expertise is evolving. It is no longer simply embodied and disseminated by a scientific authority (an individual expert in science) but is becoming polymorphous: “The forms have diversified (counter-expertise, collective expertise) to the point of plural expertise (multi-disciplinary and multi-actor) capable of articulating heterogeneous knowledge and getting actors of diverse origins to cooperate.” (Lascoumes, 2002, p.377). This would explain why, in addition to traditional popularizers (such as scientific journalists), new intermediaries are taking up the climate issue. Among them, we find the experts themselves or actors from civil society.

a. Emitters-experts

With the growing mistrust of citizens towards politicians and the media – only 24% of the world’s population would trust journalists and 63% of the world’s population would consider politicians as untrustworthy (Ipsos, 2021) – some people are trying to impose themselves as a third way. Still according to the Ipsos survey (2021), scientists would be the most trusted people after doctors. Following the example of Jouzel, Masson-Delmotte or Hansen, scientists are putting on new hats, far from research: that of popularizers. With their authority and the solidity of their arguments, their discourse has a chance of convincing and fighting against immobility.

Given the seriousness of the situation, this could become a deontological mission, a responsibility towards their knowledge in the face of the scourge of fake news, which circulate far too quickly. Valérie Masson-Delmotte has, for example, written books for children and the general public.

b. Journalists, citizens and NGOs at the service of civil society

New intermediaries are also replacing specialized journalists and scientists. They are citizens who, through new formats (Youtube, blogs, social networks…) seize the educational challenge of scientific popularization. Among these, we find for example Bon Pote and Le Réveilleur. Recently, as a student in the environment and citizen, I also decided to launch an account dedicated to these subjects: Activons Demain.

It can also be experts, such as Jean-Marc Jancovici, who make popularization one of their main activities. NGOs, in the context of their advocacy activities, are also becoming translators of scientific reports; in particular of Greenpeace, WWF and Pour un réveil écologique. Finally, non-specialized journalists are beginning to promote environmental issues in the media (Comby, 2009). However, still according to Comby (2009), generalist journalism participates in a depoliticized construction of the social world: “The points of view that persist in the spirit of political ecology, and persevere in the criticism of technical progress, economic development, etc., have little place in the French generalist media.” (p.187)

2. Which strategies?

So today, scientific popularization is no longer practiced through a one-way dissemination without exchange, but diversifies with citizen science (Bensaude-Vincent, 2010). But then, how can communication strategies be renewed to allow all these new popularizers to reach new citizens in their turn?

This happens first and foremost through a multiplication of communication formats and channels, in order to reach the general public as much as possible. “Living in the third millennium implies the acceptance of cultural diversity, the development and diversification of the means, modes and strategies of expression and communication, especially on the online media whose influence continues to grow.” (Thion Soriano-Molla, Rodriguez Moranta, 2015, paragr. 6)

For Bouchez (2018), the “climate-science” blogosphere must be strategic in order to prevail. That is to say, it must appropriate the codes of communication sciences and it must make alliances with the media and academic worlds in particular. These synergies will enhance, according to Bouchez, the knowledge around these stakes.

In their reflections on pedagogy and scientific popularization in school textbooks, Chevalier and Mourier (2012) conclude that in order to be attractive, scientific popularization must be built around a varied iconography so that the audience is attracted first by the form, and thus maximize the chances that the discourse will reach the largest possible audience. However, the authors warn of the risk that the audience will be satisfied with a: “first degree reading, poor formulation of knowledge. It is therefore advisable to question the interweaving of text and image in order to choose books and manuals that transmit quality knowledge to the target audience.” (Chevallier, Mourier, 2012, paragr. 1)

In terms of science outreach around climate change, Bouchez (2018), identifies a list of strategies for adapting information:

“- Explanation of terms and concepts (definitions of terms);

– Paraphrasing and rephrasing;

– Comparisons and metaphors;

– Examples from everyday life;

– Internet links;

– Visuals to illustrate information.

But they also identify strategies to engage the reader:

– Headlines that arouse curiosity;

– References to popular beliefs;

– Characteristics of a conversation;

– Questions that challenge the reader;

– Expressions of feelings or emotional reactions.”

(Bouchez, 2018, pp.53-54)

Although not exhaustive, this list shows the different strategies and tools of scientific popularization.

As we have seen, popularization is diverse and polymorphous. Thus, popular education could also be considered as a form of scientific popularization. Complex concept, popular education refers to processes aimed at making individuals and society evolve outside of traditional learning frameworks. (Besse, Chateigner, Ihaddadene, 2016). Still in this perspective, popular environmental education would be emancipating. It is a means of: “(…) ensuring that citizens acquire the knowledge, know-how and interpersonal skills that will enable them, both individually and collectively, to form an opinion on environmental issues and to act in accordance with these opinions.” (Bourquard, 2016, pp.21-24)

Popularizing climate change, what are the risks?

However, no phenomenon can be preserved from some criticisms. When talking about scientific popularization, it is important to know its limits in order to protect oneself as a receiver or to avoid them as a transmitter. Among the main criticisms addressed to popularization, there is first of all, the risk of simplification which would alter the subject or would be reductive. For Parrenin and Vargas (2020), terminological simplification, for example, is scientifically harmful. They for instance warn against the use of “global warming”, instead of ” climate change”.

Another risk would be the ideological orientation of some popularized contents (Parrenin, Vargas, 2020).

Micheau (2012), basing his research on scientific periodicals for children, also challenges popularization. It would be much more paradoxical than it seems. He ironizes on the complexity of this task: “Popularizing climate change is thus confronting at the same time the difficulty of making complexity understandable, making the invisible visible/concrete and translating the dynamics of a system.” (Micheau, 2012, p.43)

Finally, an important limit is that scientific communities do not systematically agree (Bensaude-Vincent, 2010). This highlights the complicated task of showing that science is a continuous dialogue and not a settled truth.

Indeed, concerning major current events, we observe that science is not always synonymous with consensus, especially if we take the example of COVID. However, this criticism of the popularization of science seems less applicable on the causes of climate change, as the scientific consensus is now really strong.

Opening new ways?

Eminently important and complex subject, popularization will undoubtedly be a lever in the fight against climate change in the years to come. Sometimes criticized, it is important to underline its limits, but the challenge of convincing the general public with scientific arguments is enormous. Pedagogy and access to quality information is necessary if we want to succeed the ecological transition. Beyond small disagreements among the scientific community, the lay public needs to understand the scientific logic of climate change to make informed decisions. Understanding scientific logic goes beyond the issue of climate change, as its consequences are so complex. Indeed, the uncertainties in time and space, as well as political and societal challenges should also be considered. Like the summary for decision-makers (IPCC, 2022), it could be relevant for the IPCC to publish a summary for “world citizens”, which would be designed for the general public.

To go further in the communication issues surrounding the transition, it would be important to use fictions and their driving force to remove social, cultural and cognitive barriers to our adaptation to climate change (Vincent, Hamilton, 2020). Science-fiction has clearly illustrated this function. It was built with the aim of awakening consciences, through stories, often dystopian.

Telling this transition through renewed imaginaries that make people want to make it happen, beyond the often alarmist talk of collapse, is a parallel and important lever. For Salmon (2021), fiction has an immense power, as, while drawing positive imaginaries, it encourages action and adaptation of territories. Lacking long-term vision and related political decisions, our societies need these imaginaries. They can be an important lever of the transition. The challenge is to mainstream the imaginaries where climate change issues are tackled.

While facing an unprecedented climate crisis, let’s keep in mind that no communication is innocent and that with great scientific information come great responsibilities.

–

Bibliography

Bensaude-Vincent, B., (2010). « Splendeur et décadence de la vulgarisation scientifique », Questions de communication [En ligne] mis en ligne le 01 juillet 2012, consulté le 26 avril 2022. DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/questionsdeco!mmunication.368

Besse, L., Chateigner, F. & Ihaddadene, F. (2016). L’éducation populaire. Savoirs, 42, 11-49. https://doi.org/10.3917/savo.042.0011

Bouchez, J., (2018). « Caractérisation des blogues de vulgarisation scientifique sur les changements climatiques » Mémoire. Montréal (Québec, Canada), Université du Québec à Montréal, Maîtrise en sciences de l’environnement.

https://archipel.uqam.ca/11578/1/M15550.pdf

Bourquard, C. (2016). Éducation relative à l’environnement, composante d’une éducation populaire et citoyenne. Cahiers de l’action, 47, 21-24. https://doi.org/10.3917/cact.047.0021

Cambridge Dictionary. (2022). Popularization définition. Consulté le 10 mai 2022, à l’adresse https://dictionary.cambridge.org/fr/dictionnaire/anglais/popularization

Chevallier, T., Mourier, A., (2012) La vulgarisation scientifique, un atout pour transmettre. Biennale internationale de l’éducation, de la formation et des pratiques professionnelles., Paris, France. ⟨halshs-00798899⟩

Comby, J. (2009). Quand l’environnement devient « médiatique »: Conditions et effets de l’institutionnalisation d’une spécialité journalistique. Réseaux, 157-158, 157-190. https://doi.org/10.3917/res.157.0157

IPCC. (2022, avril). Climate Change 2022 : Mitigation of Climate Change (No AR6). IPCC report. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/sixth-assessment-report-working-group-3/

Ipsos. (2022, 29 avril). What worries the World? Ipsos New&Polls. Consulté le 13 mai 2022, à l’adresse https://www.ipsos.com/en/what-worries-world-april-202

Ipsos. (2021). Sondage confiance des français. Opinion Publique. https://www.ipsos.com/fr-fr/seuls-16-des-francais-declarent-faire-confiance-aux-journalistes

Jerome F. (1986). Media Resource Services: getting scientists and the media together. Impact of science on society, 144, 373‑378.

Lascoumes, P. (2002). Changes in the Practice of Expertise: From the Search for a Rational Course of Action to the Democratization of Knowledge and Choices. Revue française d’administration publique, 103, 369-377. https://doi.org/10.3917/rfap.103.0369

Micheau, B. (2012). Le changement climatique dans la presse magazine : expliquer la menace, impliquer les individus, prédire la catastrophe. Communication & langages, 172, 27-51. https://doi.org/10.4074/S0336150012002037

Michigan Technological University. (2016, April 12). Consensus on consensus: Expertise matters in agreement over human-caused climate change. ScienceDaily. Retrieved May 12, 2022 from www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/04/160412211610.htm

Morton, T. (2013). Hyperobjects : Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World (Posthumanities) (1re éd.). Univ Of Minnesota Press.

Parrenin, F., Vargas, E., (2020). « Biodiversité et changement climatique : entre discours du spécialiste et discours vulgarisé », Les Carnets du Cediscor [En ligne], mis en ligne le 26 février 2020, consulté le 26 avril 2022. DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/cediscor.2817

Pouliquen, F. (2020, 9 février). Climat : La convention citoyenne a-t-elle changé les convictions de ses 150 membres ? Convention citoyenne. https://www.20minutes.fr/planete/2714551-20200209-climat-convention-citoyenne-change-convictions-150-membres

Prados, J. (2022, 21 avril). Écologie : le rendez-vous manqué du débat d’entre-deux-tours. vert.eco. https://vert.eco/articles/ecologie-le-rendez-vous-manque-du-debat-dentre-deux-tours

Salmon, B. (2021). Futurs résilients et adaptés : le rôle des imaginaires communs pour s’adapter aux changements climatiques. Communication & langages, 210, 147-166. https://doi.org/10.3917/comla1.210.0147

Scharrer, L., Rupieper, Y., Stadtler, M., & Bromme, R. (2016). When science becomes too easy : Science popularization inclines laypeople to underrate their dependence on experts. Public Understanding of Science, 26(8), 1003‑1018. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662516680311

Thion Soriano-Mollá D., Rodríguez Moranta, I., (2015). « Avant propos », Amnis [En ligne], mis en ligne le 07 septembre 2015, consulté le 26 avril 2022. DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/amnis.2701

Vincent, T. J., & Hamilton, J. F. (2020). Narrativizing Climate Change through Popular Culture. Peace Review, 32(1), 95‑102. https://doi.org/10.1080/10402659.2020.1823574