Article de Marc-Aurélien Espiaut (EnvIM 2020)

“Together, the Green Climate Fund and the International Development Finance Club (IDFC), commit to redirect the financial flux to a sustainable low-carbon development and resilient toward climate change” (Green Climate Fund, 2019) declared Rémy Rioux, the CEO of the Agence Française de Developpement, and president of the International Development Finance Club on June 26th of 2019 during the IDFC Steering Group Meeting in Casablanca. Thanks to this cooperation, the International Development Finance Club, a gathering of the 24 most important national and regional banks of development, pledges to strengthen its cooperation with the Green Climate Fund, the fund of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, with a financial power over a trillion dollar by 2025 (AFD, 2019a). This success pursue a twofold objective called by the United Nations: embracing the goals of the Paris Agreement, and increase the financing mitigation and adaptation development projects in developing countries. With this kind of declaration, the Green Climate Fund appears as the successful leader of the largest group of development banks and gains access to a tremendous amount of funding. It appears to be a victory for sustainable finance and multilateralism.

In 2020, as unilateral ambitions and major crises put regional and global cooperation to the test, we celebrated the 10th anniversary of the Green Climate Fund. Put in place in 2010 at the COP16 in Cancún, this tool was brought to life to engage cooperation between developing and developed countries against climate change, and also to satisfy developing countries in their call to help them finance it (Rantrua, 2019). In other words, countries called for trust to make change happen and to finance the change. Ten years after, IPCC predictions are more alarming than before, and the multilateralism cooperation spirit is still needed. Therefore, we are in right to ask ourselves if something happened meanwhile.

Did the Green Climate Fund manage to build the multilateralism framework it was needed to engage the fight against climate change? How did the Green Climate Fund evolved since its creation to answer the most efficiently possible the different expectations from the countries?

The overview of the Green Climate Fund’s composition and running will give us the keys to understand the different problems the Green Climate Fund has faced through the years. As a reaction to them, the Green Climate Fund engaged a great survey to tackle those issues and proposed major improvements. From difficulties and internal critics to reshaping, the Green Climate Fund’s evolution is complex. Nevertheless, it has origins a simple presentation can highlight.

The Green Climate Fund is born from a promise for a new global cooperation

First, it is important to define what multilateralism is. Multilateralism is negotiations between at least three countries. It is the will to define, in a group, rules that will be superior to the interests and judicial frameworks of the involved countries, to tackle challenges that cannot be faced by a single country. The multilateralism is a tool, but the content is defined by countries themselves. Therefore, multilateralism can be built around defense values, or protection of the environment values. For instance, for most western countries, multilateralism is put in place to promote human rights, peace, protection of the environment, and war against terrorism. This group of values is the base of their negotiation between themselves or with other countries (Ministère de l’Europe et des Affaires étrangères, 2020; Sur, 2020).

The Green Climate Fund is unique in its genre: it is the very first multilateral fund entirely dedicated to the fight against climate change. What is innovative about it is to propose funding for any competent body without any intermediate (Ourbak, 2018). Theoretically, as long as someone presents a strong project, money would not be an issue anymore. Furthermore, from the beginning, the running of the Green Climate Fund is made in a way that trust and cooperation are its major components.

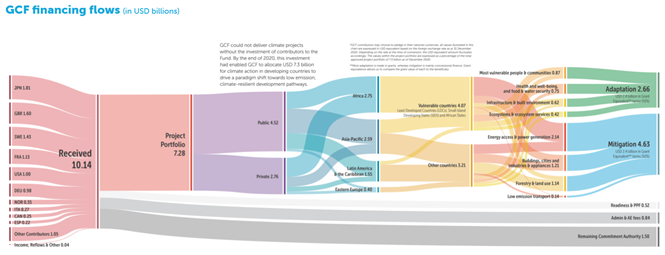

The Green Climate Fund was created in 2010 at the COP16 thanks to a consensus of 194 governments (BAD, 2019). It has two clear goals: “Bringing finance to developing countries to fight against climate change effects, and promoting projects allowing transition to low-carbon and resilient development” (AFD, 2019b). During the COP16 negotiations, 136 countries over nearly 200 stated that they will only engage low-carbon development if financial help was provided (Prager & Stam, 2019; Rantrua, 2019). Therefore, the Green Climate Fund was born from a compromise. The goal of this fund is the finance adaptation or mitigation projects of developing countries thanks to money pledged by developed countries. The money given to the Green Climate Fund only consists of grants, concessional loans and paid-in capital. In return, the money provided by the Green Climate Fund takes the form of grants, concessional loans, equity investments and guarantees (Schalatek & Watson, 2019). Several sectors are targeted: energy production and consumption, sustainable cities, low-carbon and sustainable agriculture, forests and resilience of the Small Island Developing States (SIDS). Once the Board approves a project, the Green Climate Fund provides finance for the most suited structure (regional development bank, private company, multilateral development bank, UN agency, etc…). In order to gain access to the funding, the entity must acquire an accreditation from the Green Climate Fund. This accreditation is graduated according to the ability of the entity to support and propose projects, and allows them to ask for a certain amount of money according to the rank they have (BAD, 2019; Ourbak et al., 2019). By the end of 2019, the Green Climate Fund had helped more than 10 projects to come to life, for a total amount of 5 billion dollars. Over the last years, the Green Climate Fund has known some very strong successes that testify that public banks of development are getting more and more mobilized in the fight against climate change. For instance, with the cooperation in 2016 with the Central American Bank for Economic Integration (CABEI) for promoting micro credit and entrepreneurship for very small, small and medium-sized companies in Central America to engage adaptation measures in agriculture (Ourbak, 2018), or in 2018, with the cooperation with Agence Française de Développement for developing banking and finance sectors (Commodafrica, 2018). Green Climate Fund is a powerful stakeholder that can work at regional scale, and attracts more and more development banks. Even before the COP21, when the Green Climate Fund has been announced, its creation brought hope to some governments. The number of projects proposed for the Green Climate Fund increased, as some governments of developing countries, disappointed with the experiences they had with some development banks, turned themselves to this new fund (Tubiana, 2018). Thereby, the Green Climate Fund appears as a strong, powerful and trustful partner that can mobilize around it various actors to focus on projects that have impact on climate change.

This strength is also used to mobilize private sector, which is very needed in the funding of climate change projects. Around 80% of the Green Climate Fund finance comes from donation by states, which allows the fund to target specifically risky projects, as they have low concerns about making profit out of a project, such as financing renewable energies projects, sustainable agriculture in Bhutan, or water management in Pakistani areas facing glaciers shrinkage (Bouissou, 2019). It is a way to encourage the private sector to come and finance climate compatible projects, as the Green Climate Fund assumes risks for the private sector (Rojkoff, 2017). Since 2010, the Green Climate Fund has estimated that 14 billion dollars from private finance had been invested in projects (Bouissou, 2019). The robustness of its decisions and actions sends a positive signal to the private finance, providing them with trust in the projects in which Green Climate Fund is involved (Rantrua, 2019). It is evaluated that $1 invested by the Green Climate Fund in a project attracts $2.5 from private cofunding (Levaï, 2019). In addition, it is working. Since 2013, in the sector of climate finance, the private actors finance more money for climate change related fields than the public actors (in 2017/2018, 326 billion dollars were spent by private actors, where 253 billion were spent by public actors) (Buchner et al., 2019). The increase of private actors in financing climate change projects is unmistakable, but they should be always monitored, as they are more likely to drop if any sign of instability is showing. Moreover, public financing carefully watches the benefit for public society, and respect the precautionary principle in each project, in the light of the fulfilling of the Sustainable Development Goals, as they are bound to (Navizet & Ourbak, 2018). Therefore, regulations and control can be a drag for the private sector, which is why the Green Climate Fund have to work on private co-financing stability.

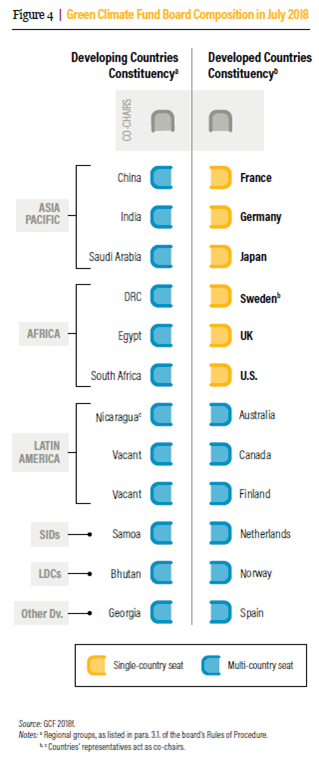

The Green Climate Fund members also wished to put in place an exemplary governance to rule this multilateral structure (Ourbak, 2018). The Board is composed of 24 members, evenly shared between two groups: developed and developing countries. Each group has 12 holders and alternates. The developing countries seats are divided according to 3 geographical areas (Asia-Pacific, Latin America, and Africa) each one of them having 3 seats, and 3 others seats (Small Island, Least Developed Countries, One developing country not included in the regional groups and constituencies before). There is no criterion to determine which country is developing or not, this is only stated by self-declaration, but countries mostly follow the UNFCCC Annex I and Non-Annex 1 lists to define themselves. Regarding the developing countries, each regional group has its own rule to determine which board member is going to be selected for a three-year term, as each regional group represent many countries. Classically, internal negotiations among countries in a same regional group are conducted to designate a board member. Sometimes, negotiations can fail, and leave a seat empty for several months, as countries did not succeeded to feel represented by only one person, like it happened for Latin America group. However, most of the time, regional group board member can be changed during a term, and often change when another regional group is changing its board member, in order to adapt the position, or when internal negotiations unfold to another compromise. The developed country group is first hold by 6 single countries, which are supposed to be the biggest contributors (France, U-K, USA, Germany, Japan, Sweden). However, the criteria are not publicly available, and if looked closely, these countries are not the biggest contributors. Then, the 6 others are between others developed countries. Here again, the criteria for countries to select their board members are not known. Unfortunately, in the developed country group, criterion are not transparent, and board memberships only remain on political agreement between all developed countries. After each round of negotiation between all the 24 countries, holders of developed countries report to their countries, but holders of developing countries report to the group of countries they belong (such as African Group of Negotiators, or Latin American and the Caribbean Group) (Waslander & Vallejos, 2018). This kind of a balanced Board is here to bring an equal ground for project negotiation, which unfortunately, is often bringing instability, as large groups have difficulties to find a common ground, and board members unresting terms are undermining the learning of negotiations. Moreover, by allowing developing countries to have a seat at the board, the fund pursues the key objective of knowledge transfer and empowerment to them (Ourbak, 2018). Thereby, the Green Climate Fund organization is coherent with its multilateral objective.

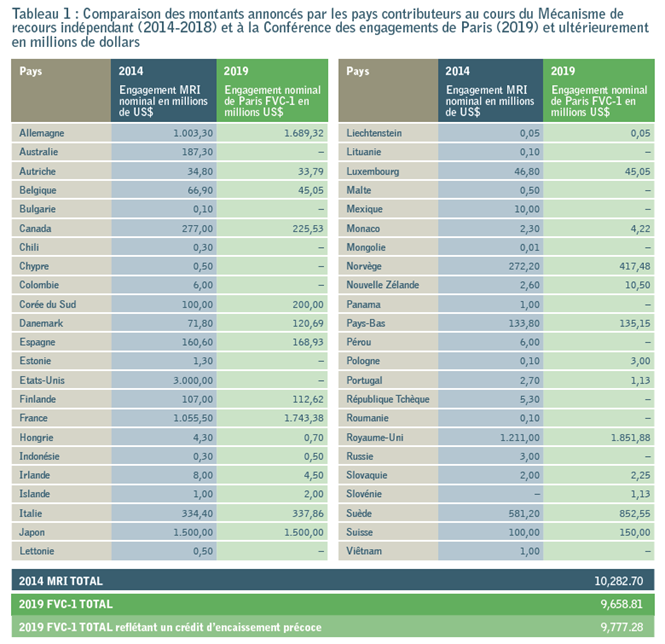

The main objective for the Green Climate Fund is to attract fundings. As a matter of fact, this goal successfully convinced some governments to pursue their efforts, but not all of them. In 2014, when the Initial Resource Mobilization event was launched, 10.3 billion dollars were promised. On the 25th of October 2019, during the First Replenishment event (the Paris conference, for the funding of the 2020-2023 period) organized by the Green Climate Fund, 9.8 billion dollars were promised (Bouissou, 2019). That is to say that the same amount of money was given. Moreover, at the time of the creation of the Green Climate Fund, the UN was calling for a 100 billion dollars worldwide pledge by 2020 (Prager & Stam, 2019). Obviously, the fund did not succeed to convince enough countries to pledge more money, to create an increasing interest for itself. On another hand, some other clues can tell us about missed goals and an internal increasing dysfunction. In the Board itself, the right for every stakeholder to speak, sustained by the idea of collective cooperation, creates confusing negotiations. It has been reported that state representatives have difficulties communicating with their states and taking a position during the negotiations. The Board members are sometimes to act by themselves, as there is a great lack of coordination between the different governments and the Green Climate Fund Board agenda.

With all of this said, does it suppose that some internal dysfunctions of the Green Climate Fund influenced its results? Many drawbacks and uncertainties about the running of the Green Climate Fund had been reported over the past years, and they can be attributed to the design of how the Green Climate Fund operates.

The running issues of the Green Climate Fund discourage the global cooperation with new stakeholders

On October 2019, for the First Replenishment of the Green Climate Fund event, several aspects of the aforesaid fund were questioned. By calling for additional funding, the Green Climate Fund puts the confidence it inspires at stake, at the mercy of the states which are ready or not to trust it again. It is also a good way to take the measure of the worldwide fight against climate change: which state or institution is willing to show itself in bright light and be upfront for the fight to come? Therefore, the First Replenishment event collected more or less the same amount of money pledged for the Initial Resource Mobilization, and was presented as a success. However, a closer look at the contributors unveil striking weaknesses (AFD, 2019).

In June 2017, the USA decided to dwindle their initial contribution and to terminate their participation in the Green Climate Fund budget in the future, in the same time they withdrew from the Paris Agreement. From the initial 3 billion dollars promised, only one was delivered on October 2019. Being despised by the first superpower in the world is a hard step to overcome, but can be balanced by the large repulsion the largest global community shared face to the systemic unilateralism strategy deployed by the US administration of the time. Therefore, the criticism it brings on the Green Climate Fund is moderated. As for money, France, United Kingdom, Germany and Norway doubled their initial contributions, which fills the gap left by the USA (Boughriet, 2019). Many countries raised their contributions, or at least matched the previous one. Only few states shrank their contribution, for instance Canada. This is intriguing because the Trudeau administration called for more climate-related actions (Yeo, 2019). Until now, questions have risen to understand why Canada “under-pledged” (Schalatek, 2019). Furthermore, several major countries decided not to take part in the Green Climate Fund replenishment process. For instance, Russia, Australia, and some oil monarchies simply did not attend the event (Rantrua, 2019). Australian government also had harsh words against the Green Climate Fund, pronounced by Scott Morrison, the prime minister, affirming, “Australia would not be throwing money into some global climate fund”. This brought the group of the 47 least-developed states to call Australia to “honor its international commitments” (Readfearn, 2018). Australian is also an example of state betting on unilateral strategy. Mr Morrison appears to be skeptical about the IPCC 1.5 degrees report that was about to be released at the time. He explained that this report do not concern his country as it only “deals with the global situation”, and that “the same report backed Australia’s policies only a year ago”. Expecting some criticism, the government declared, “Australia is not planning to provide further funding to the Green Climate Fund. We will continue to invest in climate change and disaster resilience through our existing development assistance budget, with a focus on the needs of our Pacific partners” (Readfearn, 2018). All of this appeared as a disappointment (Boughriet, 2019) and threatened to shatter the weak trust that was built a few years ago between developed countries and developing countries, as Gebru Jember Endalewn the chair of the Least Developed Countries Group explained “The Green Climate Fund plays an integral role in delivering these funds and continues to be under

resourced” (Readfearn, 2018).

Last but not least, in October 2019, the number of pledging states for the replenishment is lower than in the initial calling for funds by Green Climate Fund Board. From 45 countries in 2015, only 27 countries pledged funding for the Replenishment process (Schalatek & Watson, 2019). This drop indicates a global decrease in the trust in this fund. That would indicate that the Green Climate Fund failed to create a global dynamic, which is actually a very worrying signal sent to the private sector. As states lose their trust in the finance of climate change projects, so will the private sector. As a consequence, governments and private sectors would gather around others global funds with others diplomatic and economic goals for developing their projects, such as fund for the New Silk Roads (Levaï, 2019).

Thereby, a question dawned. What is the origin, except the strong and stubborn unilateral trend of some countries, of such loss of liability? Some clues to that question can be found in the Green Climate Fund itself. Since its creation, the running of the Green Climate Fund has had some serious issues that became public knowledge, and tainted the Green Climate Fund reputation’s.

Communication between Green Climate Fund staff and governments has been pointed out as a problem, for instance with federals states or states with little experience in negotiation. Perception between what the Green Climate Fund is and how it appears for governments, as a “climate justice compensatory device”, or a pure funding supplier, is also a problem. It calls for a change of behavior, as some developing countries were used to subsidies. Some governments are eager to collect money first and start projects quickly, but the Green Climate Fund staff is pushing for commitment of the national development agencies to take the lead and learn from experiences. Green Climate Fund staff also wants to favor a context where projects are debated, carefully thought, are the results of governance-lead projects, and fulfills some requirements, whereas some countries as Afghanistan, or South Asia countries are not used to this kind of project experiences. This situation might be hazardous, as governments might lose patience and hand their projects to funders less environment-wise uncompromising, or external consultants, which will not benefit for national development agencies (Levaï, 2019; Tanner et al., 2019). The philosophy of the Green Climate Fund is to propose as a standard the “country ownership” idea. It defines the ability of the state, or the National Development Agency, to acquire knowledge and skills, and to be able, within a few years, to propose development projects technically admissible without any external assistance needed (Le Comte, 2016). Therefore, there was a misconception about what the GFC really is in governments’ thoughts.

Secondly, the financial resources are unpredictable. Long-term strategies are impossible to put in place if every 4 years the Green Climate Fund Board does not know how much money it will collect. The $100 billion target is still far from reached, and the actual amount collected is “too low a target if it is to come from both public and private sources, and too little if it is to be spread between both adaptation and mitigation” stated Oxfam in 2014 (Waslander & Vallejos, 2018). Additionally, part of the funding provided by the Green Climate Fund Board is loans, which is disadvantageous for some countries, because of the weak bankability of some of them. Adaptation projects can take years or even more to be profitable or only financially sustainable, so expecting an investment with interest rates can be discouraging for countries that need funding the most. On a wider scale, mitigation projects are more likely to be financed than adaptation projects (44% against 23%, and 33% and cross-projects), coming from the fact, in general, adaptation projects requires much more investments, and return on investment are much easier to demonstrate on mitigation projects (Tanner et al., 2019). In addition, some countries are complaining about not being assisted for building a sustainable financial framework, which make them powerless for negotiation (Waslander & Vallejos, 2018).

Finally, the running of the Green Climate Fund Board has undergone a few issues that were brought into light and that reveals a governance issue. The Board was formally running according to the unanimity rule. If any member of the Board is against a proposition, it gets cancelled, and funding is suspended. As a consequence, passing deadlines became a habit, and caused trust issue for the Green Climate Fund Board. The selection of the represented countries at the Board is not transparent, and because of some disagreements within a regional group, some seats can remained vacant. The Board staff is getting replaced very often, favoring a great turnover and disabling the constitution of skilled staffs, common interest groups, a rise of working groups, habits and knowledge, which is more obvious for developing countries teams, as they need to grasp the running of such entity to build a negotiation knowledge. Several stakeholders even estimated that the process of selection of the Board member was not fair, not political enough, and only driven by the satisfaction of climate and environment officials (Waslander & Vallejos, 2018). One of the threats of this way of running is the loss of trust and interest because of constant instability and the lack of innovation and dynamism from the Green Climate Fund to evolve. (Waslander & Vallejos, 2018). One of the most iconic crises resulting from this way of running occurred during the 20th Board meeting in 1st-4th July 2018 in Songdo, where no decision could be reached, where the Board learned about countries lowering their pledging, and where Howard Bamsey, the former head of the Green Climate Fund, suddenly resigned (Ourbak, 2018). The new head, Yannick Glemarec became the third head of the Green Climate Fund in 5 years. As a matter of fact, the Board itself does not send positive signals to external stakeholders and to the states to increase their cooperation. A last very important remark raised by the applicants to the funds themselves are the “complex procedures” and “capacity constraints” to gain access to the funds. The Board promoted a “paradigm shift”, but it does not give a way for it. Some countries, or national development banks, are not mature enough to have the knowledge, the experience it gets to enter the application process efficiently, and some national development agencies even lack knowledge about climate change or sustainable development. Green Climate Fund funding application is difficult, applicators countries need to present a strong and very technical file with a complex financial framework, and the application process takes a very long time. Moreover, the fund does not provide support to applying structures and financial engineering assistance, which implies many adjustments during the process and additional costs (Waslander & Vallejos, 2018; Tanner et al., 2019; Schalatek & Watson, 2019). In others words, there is a lack of support by the Green Climate Fund staff.

All of this altogether sent discouraging signals of poor governance, finance irregularity, and weak cooperation to states, banks of development, national development agencies, private sector and civil societies. This participated in the weakening of a strong multilateral framework supposed to act against climate change, as it brought evidences of unilateralism, top-down management, opacity of negotiations, and flash in the pan impressions. Fortunately, the Green Climate Fund Board became aware of short-term risks and started to look into its cogs to understand where it was seizing, and work on it.

The Green Climate Fund acted quickly to improve its ruling, to show its betterment skill to the world and to keep the trust high

Because of the crisis of July 2018, the new head of the fund, Yannick Glemarec, worked hard to improve its running. The task was hard, consisting in improving the existing bodies of the Green Climate Fund, working on the increase of pledges, improving the project approval and disbursement processes. Giving trust back to the private sector appeared also as an absolute necessity, as mentioned by Alexandra Tracy, the Climate Markets and Investment Association representant to the Green Climate Fund (Prager & Stam, 2019; Schalatek & Watson, 2019). Self-conscious of this crisis, the Mr Glemarec decided to entrust Independent Evaluation Unit to conduct an audit of the running of the different bodies. In February 2019, during the 22th Board meeting, Independent Evaluation Unit, exposed its conclusions, and on the 7th July of 2019, the Boad voted the improvements propositions of this audit (Prager & Stam, 2019). Four main ideas were presented (Independent Evaluation Unit, 2019b; Lipton, 2020):

First of all, countries assistance in the designing of project has to be reinforced. The fund has to improve its relationship with countries, or with national development agencies, and assist them in their project development process. The assistance should be proactive in the search of solutions, thanks to a reinforced proximity, or to the capacity to connect different entities that can assist each other. To this end, keys performance indicators must be developed in order to measure transparency, speed, impact, etc, in order to improve the quality of the project proposals. Secondly, the Green Climate Fund has to work as a leader and settles in not mature markets, in order to take the most of the risk, and to attract private finance. It has the responsibility to give the impulse to attract attention on innovative striking technologies. One main idea for this is the creation of impact bonds. The issuing entity of the bonds looks for someone to take a great risk by financing innovative project, but proposes in return very high interest rates. So far, there are not enough feedbacks to assess the benefit for an external investor. Next, the funds have to be more balanced toward adaptation projects, and propose various funding devices instead of grants or loans only (guarantees, impact investing) to attract more private finance. In this purpose, the institute Action on Climate Today proposed the Financing Framework for Resilient Growth tool, planned to help building connections between a project and a bank that can finance it, but also quantify adaptations costs and benefits (Tanner et al., 2019). Also, better co-financing strategies should be put in place in order to attract private part to invest in it, as the investment risk seems lower. One recent project is iconic of that: The Karachi 0 carbon bus network, where 90% of it was co-financed with different grants and loans. Finally, the Board has to delegate some competencies to the Secretary, to rethink its way of taking decisions, to improve transparency and to conduct more feedback analysis of itself. Unanimity cannot be the only way of voting, because it led too many times to immobility. The Board has to vote for another way of taking decision. Recently, the approval of a project about which 4/5th of the Board members agreed while 4 members of developed or developing countries refused was voted (Schalatek & Watson, 2019). Board members should be elected according to their skills, for a 3 years term. The Secretary has to play a bigger role on the relationship with states, management of the teams and communication with external elements. It can have a bigger role on the moderation of the Board, on groups cohesion, filling seats vacancies, supervising selection of board members. The allocation of new competencies should bring balance the power of the Board, bring more dynamism and professionalism, and increase communication between all stakeholders (Waslander & Vallejos, 2018; Green Climate Fund & Independent Evaluation Unit, 2019a; Lipton, 2020).

To gain trust back, the Green Climate Fund also has to work on new alliances. It has to work on its duty of exemplarity, and refuses cooperation with banks and states funding production of fossil fuels, as the recent partnerships with Deutsche Bank, HSBC or Crédit Agricole, and seek for partnerships with strongly invested entities, like International Development Finance Club (IDFC) (Le Comte, 2016). In October 2018, the Agence Française de Développement (AFD) and the Green Climate Fund officialized a strong collaboration, where the AFD gained privileged access to funds, in a spirit of a full respect of the Paris Agreement. This agreement will favor the passing of knowledge, funds and technical assistance between the two institutions and beyond, and will work on the improvement of the adaptation projects (AFD, 2018). The recent cooperation with IDFC is also a very good signal. In a general way, the Green Climate Fund has to work on its cooperation, but also on the passing of knowledge between national development agencies, the Green Climate Fund, the international banks, etc. Also, working at local and national scale is needed. National agencies, civil societies, small-sized companies or ministries are in need for knowledge related to climate change, and already organized themselves at infra-state or state scale. Therefore, it is all about helping them, giving them tools, integrating them in the shaping of a project and creating knowledge loop.

Conclusion

For the Green Climate Fund, the year 2020 was about the implementation of these new recommendations. Now, a new phase opened, where the fund has to convince back many states that withdrew themselves from the boldest multilateral cooperation. Global multilateralism is not to be taken as granted, and should always be checked as countries are tempted to defend their own interests first. The Green Climate Fund is a reservoir of tools and ideas for the XXIth century, for building the sustainable development that is needed for the climatic challenge to come. Communication, cooperation, free circulation of ideas, tools and knowledge at any scale and between any stakeholders are the keys the Green Climate Fund apply and should promote globally in order to face the upcoming challenge. Something has to play the role of the leader, the driving force, and be the first one to apply what everybody thought it was impossible years before, and it should be the Green Climate Fund.

–

Bibliography

AFD. (2018, octobre). Le groupe AFD en partenariat avec le Fonds Vert pour le Climat lance le plus important programme de son histoire pour accroître les financements climat des institutions financières locales de 17 pays. https://www.afd.fr/fr/actualites/communique-de-presse/le-groupe-afd-en-partenariat-avec-le-fonds-vert-pour-le-climat-lance-le-plus-important-programme-de-son-histoire-pour-accroitre-les-financements-climat-des

AFD. (2019a, septembre 24). UN Climate Summit : Development Banks make major Commitment. AFD. https://www.afd.fr/en/actualites/un-climate-summit-development-banks-make-major-commitment

AFD. (2019b, octobre 24). 2019, année décisive pour le Fonds vert pour le climat. https://www.afd.fr/fr/actualites/2019-annee-decisive-pour-le-fonds-vert-pour-le-climat

BAD. (2019, avril 18). Fonds vert pour le climat. Groupe de la Banque Africaine de Développement; African Development Bank Group. https://www.afdb.org/fr/topics-and-sectors/initiatives-partnerships/green-climate-fund

Boughriet, R. (2019, octobre). Fonds vert pour le climat : 9,8 milliards de dollars pour 2020-2023. Actu-Environnement; Actu-environnement. https://www.actu-environnement.com/ae/news/fonds-vert-finance-34305.php4

Bouissou, J. (2019, octobre 26). Le Fonds vert pour le climat va recevoir 9,8 milliards de dollars. Le Monde.fr. https://www.lemonde.fr/economie/article/2019/10/26/le-fonds-vert-pour-le-climat-va-recevoir-9-8-milliards-de-dollars_6016997_3234.html

Buchner, B., Clark, A., Falconer, A., Macquarie, R., Meattle, C., & Wetherbee, C. (2019, novembre). Global Landscape of Climate Finance 2019. Climate Policy Initiative. https://climatepolicyinitiative.org/publication/global-landscape-of-climate-finance-2019/

Commodafrica. (2018, octobre 24). $280 millions du Fonds Vert à l’AFD pour développer la finance climat en Afrique. Commodafrica. http://www.commodafrica.com/24-10-2018-280-millions-du-fonds-vert-lafd-pour-developper-la-finance-climat-en-afrique

Green Climate Fund. (2019). Green Climate Fund and the International Development Finance Club signs a Statement of Partnership to join forces in fighting climate change. Green Climate Fund; Green Climate Fund. https://www.greenclimate.fund/news/green-climate-fund-and-international-development-finance-club-signs-statement-partnership-join

Independent Evaluation Unit (IEU), 2019a. Forward-Looking performance review of the Green Climate Fund – Final Report. Green Climate Fund Independent Evaluation Unit.

Independent Evaluation Unit (IEU), 2019b. Summary of the Review: Findings from the IEU’s forward-looking performance review (2 of 4).

Le Comte, A. (2016, mai 10). Fonds vert : Comment en faire un outil efficace de lutte contre le changement climatique. ID4D. https://ideas4development.org/fonds-vert-faire-outil-efficace-de-lutte-contre-changement-climatique/

Levaï, D. (2019, novembre 5). Reconstitution du Fonds vert pour le climat : Une occasion manquée. ID4D. https://ideas4development.org/reconstitution-fonds-vert-climat-occasion-manquee/

Lipton, G. (2020, mars 2). A decade old, the Green Climate Fund receives its first pulse-check. Landscape News. https://news.globallandscapesforum.org/42907/a-decade-old-the-worlds-largest-climate-fund-receives-its-first-pulse-check/

Navizet, D., & Ourbak, T. (2018, septembre). Une mobilisation croissante des acteurs de la finance climat. The Conversation. http://theconversation.com/une-mobilisation-croissante-des-acteurs-de-la-finance-climat-101536

Ourbak, T. (2018, octobre). Fonds vert pour le climat, des projets malgré tout. The Conversation. http://theconversation.com/fonds-vert-pour-le-climat-des-projets-malgre-tout-105356

Ourbak, T., Mercier, E., & Rojkoff, A. (2019). L’AFD et le Fonds Vert pour le climat : Retour d’expérience.

Prager, A., & Stam, C. (2019, juillet 9). Le Fonds vert pour le climat cherche sa voie. www.euractiv.fr. https://www.euractiv.fr/section/climat/news/le-fonds-vert-pour-le-climat-cherche-sa-voie/

Rantrua, S. (2019, novembre 27). Fonds vert pour le climat : Enfin plus utile à l’Afrique ! Le Point. https://www.lepoint.fr/afrique/fonds-vert-pour-le-climat-enfin-plus-utile-a-l-afrique-27-11-2019-2349831_3826.php

Readfearn, G. (2018, octobre 10). Poor countries urge Australia to honour Green Climate Fund commitments. The Guardian. http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2018/oct/10/poor-countries-urge-australia-to-honour-green-climate-fund-commitments

Rojkoff, A. (2017, novembre 16). AFD et Fonds vert : Multiplier les impacts des projets pour le climat. ID4D. https://ideas4development.org/afd-fonds-vert-climat/

Schalatek, L. (2019, octobre). Pledges in Paris were a start, but not yet enough to signal real Green Climate Fund replenishment ambition | Heinrich Böll Stiftung | Washington, DC Office—USA, Canada, Global Dialogue. Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung. https://us.boell.org/en/2019/10/29/pledges-paris-were-start-not-yet-enough-signal-real-gcf-replenishment-ambition

Schalatek, L., & Watson, C. (2019). Le Fonds Vert pour le Climat—Fondamentaux du financement climatique 11.

S.E.H. (2019, juin 26). Développement durable : L’IDFC et le Green Climate Fund signent à Casablanca un partenariat pour le financement de projets verts. LeBoursier.ma – Site d’information. https://www.leboursier.ma/Actus/4987/2019/06/26/Developpement-durable-l-IDFC-et-le-Green Climate Fund-signent-a-Casablanca-un-partenariat-pour-le-financement-de-projets-verts.html

Tanner, T., Bisht, H., Quevedo, A., Malik, M., Nadiruzzaman, Md., & Biswas, S. (2019). Enabling access to the Green Climate Fund : Sharing country lessons from South Asia. ACT Action on Climate Today and Oxford Policy Management. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/333547254_Enabling_access_to_the_Green_Climate_Fund_Sharing_country_lessons_from_South_Asia

Tubiana, L. (2018, juillet 19). This is not the end of the Green Climate Fund, but its next steps are critical. news.trust.org. https://news.trust.org/item/20180719154640-yj9ih/

Waslander, J., & Vallejos, P. Q. (2018). Setting the Stage for the Green Climate Fund’s First Replenishment. World Resources Institute.

Yeo, S. (2019). Green Climate Fund attracts record US$9.8 billion for developing nations. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-019-03330-9