par Noémie Levé (EnvIM 2018)

Plastic is great, it is lightweight, durable, versatile, hygienic, resistant, and above all cheap. It comes in every shape, color, size and texture. It has transformed our lives for the better in many ways. For instance, plastic bottles allow billions of people to have access to clean water every day, and it helped the space conquest thanks to its strength and weight properties. Without the lightness of plastic, our planes would be even bigger energy consumers, and would fly slower. Thanks to its ability to prevent contamination, plastic is a perfect material for sterile medical devices and can be transplanted in the human body. To sum up, plastic saves lives.

We love plastic so much that we have produced 8.3 billion tons of it since 1950 (Geyer et al., 2017). If we translate this weight into famous soda bottles equivalent and line them all up, we could cover our Planet 3.1 times with them. Our appetite for plastic has been growing in the last years, as 50% of the entire production had been produced in the last 15 years (Geyer et al., 2017).

But the plastic honeymoon phase has come to an end. We face the consequences of this blind love, as plastic waste drifts in the oceans and micro plastics crawl up the food chain from our meals to our bodies. From the 8.3 billion tons ever produced, 6.3 billion tons have been discarded, from which 9% was recycled, 12% burnt, and the remaining 79% piles up in landfill or nature (Geyer et al., 2017). This means that the Earth is still figurately covered 2.4 times by soda bottles.

The ocean plastic pollution strongly indicates that our system needs to be reset. We have all seen pictures of whales with plastic in their bellies, or waves covered by plastic garbage. One truckload of plastic is dumped in the ocean every minute, 40% of which was used only once (Geyer et al., 2017). It is also noteworthy that plastic that ends up in the ocean mostly comes from rivers. Only 10 of the world’s rivers are responsible for 90% of the plastic waste present in the oceans. Eight of these rivers are in Asia, two in Africa (Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research, 2017).

If we continue at this pace, scientists have calculated that there would be more plastic than fish in the sea by 2050 (World Economic Forum, 2016). Our plastic waste would travel through the seas for another 450 years until they are fully disintegrated… Most likely into microplastic.

In addition to the environmental damage, the financial loss is large. The European Commission found out that marine litter costs the European Union $295 million to $793 million per year. These figures encompass the loss of economic value from the disregarded material, the costs of cleaning up the coastline and negative effects on tourism, shipping and fisheries.

Turning off the plastic tap

In reaction to the alarming situation, different programs have been initiated to clean up the plastic seas. The first Ocean Cleanup program was launched this September in San Francisco. The system is meant to be deployed in the world’s largest plastic accumulation zone in the Ocean, the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. 1,8 trillion pieces of plastic are spread over this area which is twice as large as Texas (Ocean clean up, 2018). If successful, this ambitious program aims at scaling up its fleet to 60 systems on the great Pacific Garbage Patch over the next two years, and ultimately reduce the amount of plastic in the oceans around the globe by at least 90% by 2040.

The plastic pollution cannot be solved completely by solely cleaning up after us, while continuing to use plastic for almost everything. The problem needs to be treated at its source and rapidly. Many organizations and governments have been accelerating deploying regulations to either encourage its collection and recycling or limiting its production. Below are significant examples of the important steps forward that have been taken lately:

US cities targeting plastic straws

In the United States cities and companies have decided to tackle this issue one plastic straw at a time. Last July, Seattle became the first major US city to ban plastic food packaging and straws from its food service businesses; this includes all the disposable food service items such as containers, cups, straws, utensils, and other products (Seattle.gov, 2018). Washington DC, New York City, and Miami should follow soon. From 2019, consumer in California will have to ask if they want a straw. Large companies like Starbucks, American Airlines, Marriott hotels and McDonalds are reacting to the change in consumer behavior and emerging municipal measures and vowed to stop offering plastic straws (Gibbens, National Geographic, 2018).

India large cities, single-use plastic use synonym of jail

Being the second largest populated country and due to its fast-growing economy, the Indian society is firsthand witness of the plastic overdose and sees the effect of the uncontrolled consumption and unregulated treatments. After the massive illegal plastic burning was denounced by the population, the Delhi municipality banned in 2017 single-use plastic from its city. Bags, tea cups and cutlery are part of the scope. More recently, in June 2018, Mumbai has followed Delhi’s path. Mumbai residents caught using single-use plastic are now fined about 300€ and subject to three-month imprisonment penalty. This sentence might seem harsh yet is nothing compared to the Kenyan justice. In Kenya, one would be charged a $38 000 fine and four years of jail if found using, producing, or selling a plastic bag (Watts, the Guardian, 2018).

France, the circular path

In August 2018, the French government announced that products and packaging that are not made out of recycled plastic will be taxed from 2019 onwards. In an interview for the Journal du Dimanche, the French Secretary of State to the Minister for the Ecological and Inclusive Transition, explained that the difference in price could reach 10% of the good’s price. This aims at encouraging consumers to purchase recycled products and producers to favor the use of recycled plastics, as well as increasing the need for recycled plastics solutions, recycling streams and infrastructure growth.

Later in September this year, the French National Assembly voted the ban of plastic packaging cutlery, plates and straws from 2020 onwards.

These decisions follow the launch of the French Circular Economy Roadmap in April. Among 50 other measures that cover France’s ambition to move towards more sustainable and circular society, the roadmap draws the intention of the French government to allow the distribution of only recycled plastic by 2025. It describes two other measures that would encourage the recycling streams, such as a deposit for plastic bottles, and taxation that would make it more beneficial to value waste instead of discarding it.

Europe, world’s most ambitious single-use plastic ban

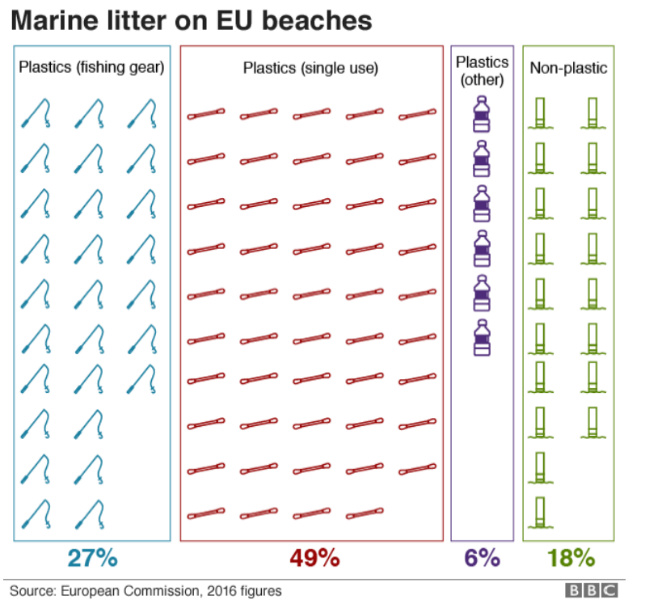

Shortly after France announcement, the European Union largely voted in favor of the ban of the ten most single-use plastic polluters found in the ocean (571 votes to 53). As shown on the picture, the single-use plastic account for almost half of the marine litter found on beaches. This regulation became definitive in December, and should be formally adopted in early 2019. It would make Europe the world leader in tackling the plastic pollution crisis. From 2021, single-use plastic such as cotton swabs, disposable plates and cutlery should join the Minitel into the objects of the past museum. Single-use plastic that do not currently have an alternative, like burger and sandwich boxes are not part of the list but should be reduced by 25% by 2025. The regulation targets the recycling of plastic bottles as well, from which 90% should be recycled by 2025.

“We have adopted the most ambitious legislation against single-use plastics,” said Frédérique Ries, the member of the European Parliament who drafted the bill. “Today’s vote paves the way to a forthcoming and ambitious directive,” she added. “It is essential in order to protect the marine environment and reduce the costs of environmental damage attributed to plastic pollution in Europe, estimated at 22 billion euros by 2030.”

Ellen McArthur Foundation and 275 companies draw a line in the sand

At the end of October, on the impulsion of the Ellen McArthur foundation and the UNEP, 275 companies including brands, retailer, recyclers, governments and NGO have committed to ban all single-use plastic and to invest in new technologies, so all packaging can be recycled by 2025.

The signatories list is impressive and includes well-known consumer businesses such as Danone, H&M Group, L’Oreal, Mars Incorporated, and Unilever. Three of the most polluting companies Coca-Cola, PepsiCo and Nestle (according to an index by the Break Free from Plastic movement) agreed to be part of the movement. It should develop globally the roots of a “new norm” for plastics.

As Ellen MacArthur described it: “Even some of the biggest brands in the world cannot solve this on their own. They have been trying to, and they have not been able to. You can’t solve a systemic change on your own. You need to change the system” (Ellen McArthur, 2018). Even if some companies taking part in these agreements compete directly on the markets, they understood the mutual benefit of tackling these issues jointly. They should compete on their soda taste, not pollution rates.

The following targets were defined (Ellen McArthur foundation news report):

- Eliminating problematic or unnecessary plastic packaging and moving from single-use to reusable packaging models.

- Innovating to ensure 100% of plastic packaging can be easily and safely reused, recycled, or composted by 2025.

- Circulating the plastic produced, by significantly increasing the amounts of plastics reused or recycled and made into new packaging or products.

To assure transparency and keep the momentum, businesses are bound to publish their results yearly. As another sign of commitment, $200 million has been pledged by five venture capital funds to create a circular economy for plastic (Ellen McArthur foundation, 2018).

A sudden call for action? Chinese countermeasure.

2018 seems to be the year of plastic revolution, as governments and major western companies tend to now all agree on the urgency of transforming the plastic system. This shift was encouraged by the unilateral decision, earlier this year, from China to ban its plastic waste importations. Since 1992, China has welcomed half of the world’s plastic waste (Laville, Le Monde, 2018). In most cases, it was cheaper for the western world to ship their waste to China than processing these domestically. Because of its fast-economic development and its own plastic waste increasing, China can no longer handle the western waste.

Limited by their own infrastructure, the western nations have no other choice but to find fast, innovative and systemic solutions to tackle this issue.

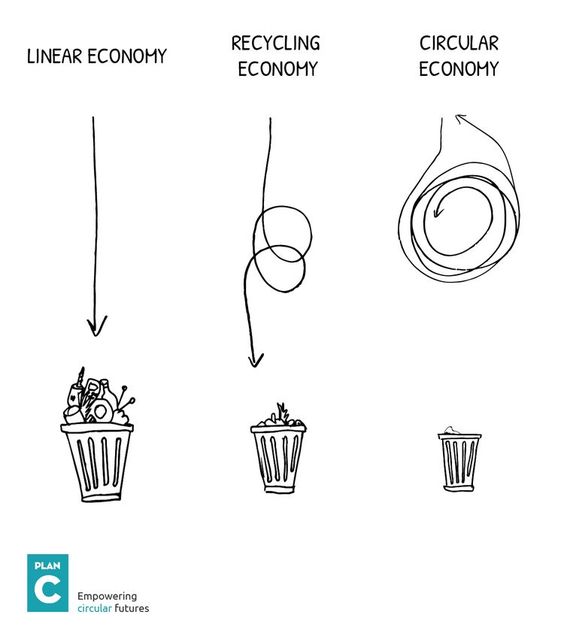

Solutions crystallize around two main directions: recycling and banning plastic (as shown on the figure bellow.)

The recycling case

Recycling more plastic is considered by many companies and governments as part of the solution. When recycling is feasible, it is energy efficient and requires 88% less energy than making new plastic. Significant amounts of plastic waste are produced every day or are readily available in the nature. Instead of destroying them, these could be used as primary material to develop new objects. Some companies and scientists have been working on reintegrating these “lost plastic” into the value chain. You can now run in Adidas runners partially made out of ocean plastic, and next year you will be able to relax in an ocean-bound plastic chair designed by the collaboration between Ikea and the Next Wave Project.

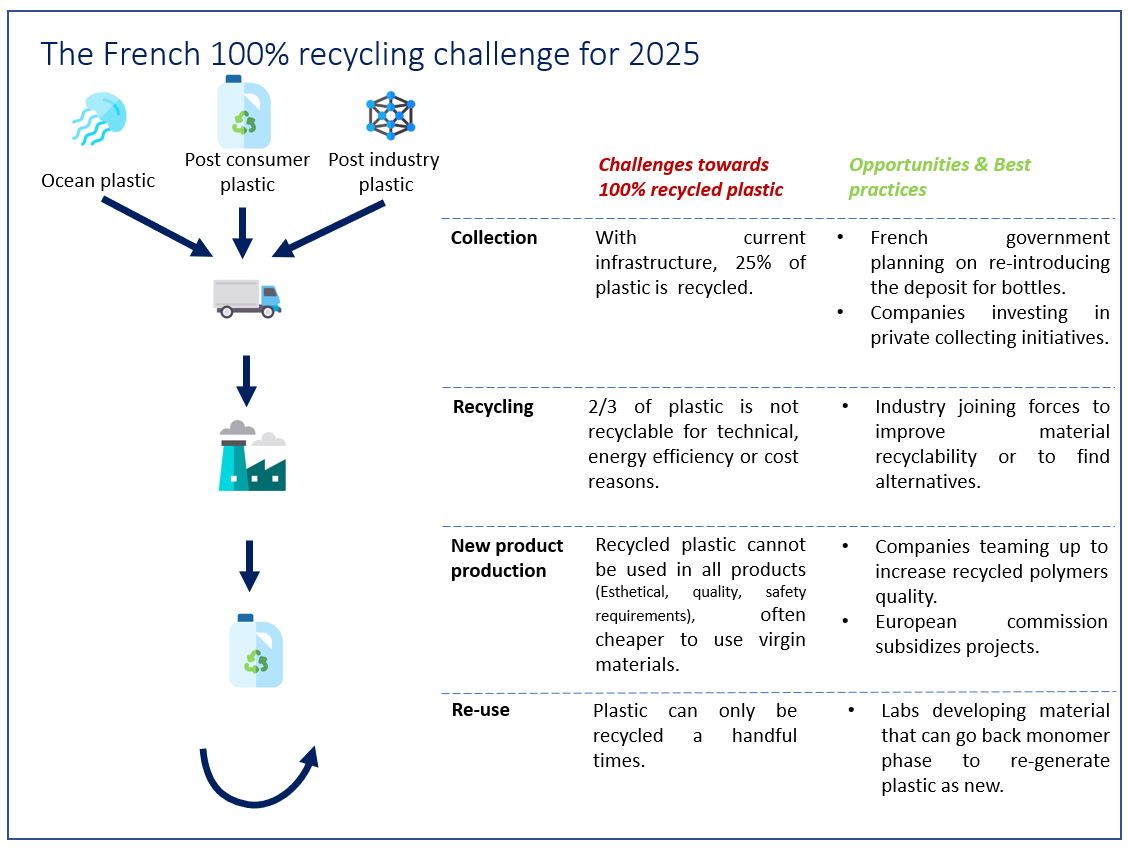

Companies and European countries have set ambitious targets to encourage plastic recycling around the continent. France aims at having 100% plastic recycled towards 2025. Currently 25% of the plastic in France is recycled (60 Million Consumers, 2018), so the journey ahead promises to be intense and challenging. The figure bellow describes this plan challenges and opportunities.

Collection opportunities:

In the circular economy roadmap, France exposes its will to bring the deposit back. This scheme was the norm in France till the 1980s, and still running successfully in many European countries. Norway, for example collects up to 97% of its plastic bottles, thanks to deposit machines available in supermarkets (Taylor, National Geographic, 2018). 92% of these bottles are used for the same quality products. Consumer brands like Danone are also investing in private collection solutions.

Recycling opportunities:

With current common recycling processes, for technical, energy efficiency or cost reasons, only one third of plastic is recyclable. However, companies and labs are both working on improving materials recyclability and alternatives such as bioplastics or biodegradable plastic (Ellen McArthur initiative, Evian, Danone). These alternatives are still budding and cannot be considered for stringent usages, and some are also controversial.

It is noteworthy to indicate that, for many consumers, biodegradable and compostable plastic are synonyms, and means that the concerned plastic products decompose in nature or a home composter. In fact, only compostable biodegradable plastic complies with this definition. According to the ISO 17088, to be compostable, a material needs to disintegrate at the same rate as plants into organic compounds that do not disrupt the compost quality. Whereas, biodegradable plastic refers, more largely, to plastic that can deteriorate into smaller compounds, with no requirement on the deterioration time or chemical and physical residues properties. Biodegradable polyethylene (PE) is a frequent example of non-compostable biodegradable plastic. This material is a standard PE mixed with additives to increase its fragmentation speed, into tiny plastic pieces. The additives integrated in the non-compostable biodegradable plastic prevent its traditional recycling, as it would decrease the recycled material quality. Biodegradable plastic is not always a more environmental friendly solution.

New product production:

Plastic can be used for multiple purposes and has high technical and aesthetical requirements in some cases. Recycled plastic cannot so far be re-used for all demanding applications. It is very difficult for industries to find recycled plastic that deliver on their standards and within their budget. However, companies, laboratories and governments join effort to improve recycled plastic quality:

- Suez teaming up with Plast’Lab laboratory and Lyonbasell to increase the recycled plastic quality and bring recycled polymers quality at the same standard as virgin polymers.

- European commission launches subsidies to help companies developing recycled polymer qualities.

Re-use opportunities:

When recyclable, recycled plastic qualities deteriorates after few recycling cycles. The current wide spread recycling techniques are only reshaping the material and decreasing its properties, plastic is not a circular material. Laboratories are working on depolymerization through thermo, chemical or catalyzation processes to develop plastic that would be infinitely recyclable (Shaver, 2018) and increase its value at the end of life, like metal. The Colorado State University created a polymer that can be broken at lower temperature into its monomers and would then be countlessly recyclable at the same quality level. To assure its success, lots of effort will be required to scale up these processes in an energy and cost-efficient manner.

To conclude, plastic has been developed and used so far with limited considerations of its end of life. Until recently, plastic waste had no value, it was most of the time cheaper to produce new products with virgin materials than recreating material out of its molecules. This led to highly performing material, with very finite value at the end of the chain, and partly explains the socioeconomic challenge we are facing today. There is an opportunity to work out the complete supply chain value streams and to develop alternatives that are energy, technically and cost-efficient throughout the complete life-cycles.

A life without plastic

The debate around single-use plastic gained such momentum recently that “single-use” was awarded the 2018 word by Collin’s dictionary, and succeeds to the 2017 word: fake news.

40% of the garbage found in the oceans are single-use plastic, so if implemented globally, especially in the biggest plastic pollution emitting countries, single-use plastic bans can help to turn off the plastic tap. The European regulation examines only products that already present an alternative. Hence, we should study the alternatives carefully, and prevent shifting the problem elsewhere.

If we take the example of the straw, banning the plastic version makes room for alternative materials to flourish. We become more creative in finding solutions to drink our orange juice, with materials such as bamboo, metal, or cardboard. This results in a primary advantage: material source diversity. If we are no longer relying on one material to perform the same function, then the impact on the different resources could be more balanced, especially if the solutions are designed with local resources. On the other hand, the industry and scientists are incentivized to develop new materials that could have the same properties as plastic but with a reduced environmental impact, and closer to nature such as bioplastics. Two Dutch designers, Maartje Dros and Eric Klarenbeek are using potato starch, cocoa beans or algae to 3D print objects. They believe that their materials could replace entirely fossil fuel-based materials from table wear to shampoo bottles. Aside being fully biodegradable, algae-based material could help to reduce CO2 rates in the atmosphere during its “manufacturing growth” through the photosynthesis process. “It’s about thinking beyond the carbon footprint: instead of zero emissions we need ‘negative’ emissions” explain the two designers.

However, one should be aware that everything has an impact. If society substitutes single-use plastic straws by single-use wooden straws for example, by being biodegradable in nature it could prevent ocean pollution, but what would happen at the other end of the chain? Would there be an effect on deforestation, on water supply, on the product affordability? In order to provide the best solutions, it is crucial to consider the object entire life cycle, environmental, economic and societal impact.

When well used and treated, plastic can be more environmentally efficient than other materials.

When doing grocery shopping, we often accept paper bags instead of conventional plastic grocery bags, thinking they are better for the environment. In a sense, it is true, if discarded in the environment the paper bag will decompose, and the plastic bag will not. Multiple Life Cycle Assessment studies have been done on grocery bags options, although the studies show different numbers, the trends stay similar and question the bans of plastic bags. The conventional plastic bag has less environmental impact than the paper version, and even more than the cotton version. A Canadian study shows that one should use a paper bag 4 to 28 times depending on the environmental indicators (e.g. fossil fuel usage, impact on human and ecosystem health) to balance out their impact compared with the plastic version (CIRAIG, analyse du cycle de vie des sacs d’emplettes au Quebec, 2017). Although, the paper bag low resistance to weight and rain will most likely make it impossible to be used more than twice. The same study shows that a re-usable cotton bag should be used 100 to 3 657 times to balance out its impact with the studied scenarios and indicators.

The issue here is not plastic itself but the fact that it is so easy to acquire and simply be discarded. Consumer awareness is lacking as well as means to help them make the best choice. Finally, especially in emerging countries like India, which banned single-use plastic, hygiene and health problematics have risen. Suitable alternatives are not always directly available for the population, and observers report, for example, people carrying meat in newspaper whereas they would have done it previously in clean plastic bags.

Stop blaming plastic and redefine the system?

Governments and municipality are globally encouraging recycling and single use plastic ban to answer the plastic crisis. However, both solutions present limitations. Recycling is technically challenging, costly, energy and resource consuming. With the increasing population and emerging countries economic growth, plastic need and production is meant to continue its consequential growth, and recycling system solely cannot keep up. Alternatives to single-use plastic, especially if replaced by another single use product could simply deviate the concern. In order to tackle durably this issue, companies could avoid the use of resources and waste generation by re-inventing their business models and value creation, and develop re-use scheme for instance. In countries like Germany, bottles are not collected to be recycled, but to be cleaned and re-used. In France, startups like Lemon tree are innovating towards this solution. Lemon tree equips stores with liquid dispensers (from a variety of organic oils, vinegar and wines), as well as clean bottles, that consumers can give back once emptied and get an incentive in return. The bottles are cleaned and brought back into the cycles.

Limiting material production and promoting re-use is one of the options given to Ellen McArthur foundation commitment signatories. Yet, so far, many companies have acted to preserve their conventional linear business models; they have favored the recycling option, and are designed to sell an increasing amount of plastic items. The international community has realized the plastic pollution issue; but looking at the socio economic challenges our world is facing, more benefit could emerge from redefining holistically its design, production, consumption and treatment schemes.

References:

- Break free from plastic, 2018, “Branded in the search of world’s top corporate plastic polluters”.

- CIRAIG, 2017, « analyse du cycle de vie des sacs d’emplettes au Québec » .

- Ellen McArthur foundation, 2018, “ ‘A line in the sand’ – Ellen MacArthur Foundation launches New Plastics Economy Global Commitment to eliminate plastic waste at source”.

- Geyer et al., 2017, Science Advances, “Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made”.

- Gibbens, 2018, National Geographic, “A brief history on how plastic straws took over the world”.

- Laville, 2018, Le Monde, «Sus au plastique ! Les dessous d’une « décision vertueuse »… ».

- Ocean clean up, 2018, “the world’s first ocean cleanup system launched from San Francisco”.

- Schmidt, 2017, Environ. Sci. Technol., “Export of Plastic Debris by Rivers into the Sea”.

- Seattle.gov, “2018, Food Service Packaging Requirements”.

- Shaver, 2018, DIF “Plastics problem and possibilities”.

- Taylor, 2018, National Geographic, “You Can Help Turn the Tide on Plastic. Here’s How”.

- Watts, 2018, the Guardian, “Eight months on, is the world’s most drastic plastic bag ban working?”.

- World economic forum, 2016, “The New Plastics Economy report”.