Article de Hssine Benhrouz (MS EnvIM 2022-23)

Introduction

For over seven decades, the field of economics has been predominantly fixated on Gross Domestic Product (GDP) as the primary metric of progress, measuring a nation’s economic health based solely on its output.

But “what if we started economics not with its long-established theories, but with humanity’s long-term goals, and then sought out the economic thinking that would enable us to achieve them ?”. This question was raised by Kate Raworth in her book “Doughnut Economics : Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist.”

In this book, Raworth introduces the concept of a Doughnut Economy, marking a transition from old to new economic thinking with a broader objective for the twenty-first century’s economy: ensuring the fulfillment of human rights for every person while respecting the capacity of our life-sustaining planet. Raworth’s revolutionary concept is not confined to theoretical discourse but has rapidly gathered momentum in practical implementation and has gained traction globally, with over 70 cities worldwide embracing its principles today.

Now, what precisely does the Doughnut Economy concept entail ? And how can this innovative concept be applied at the city level, and specifically, how is Amsterdam leading this transformative effort ?

Understanding the Doughnut Economy

The term “doughnut economy” refers to an economic model that seeks to balance human well-being with planetary boundaries. As highlighted before, it was popularized by the economist Kate Raworth in her book “Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist.”

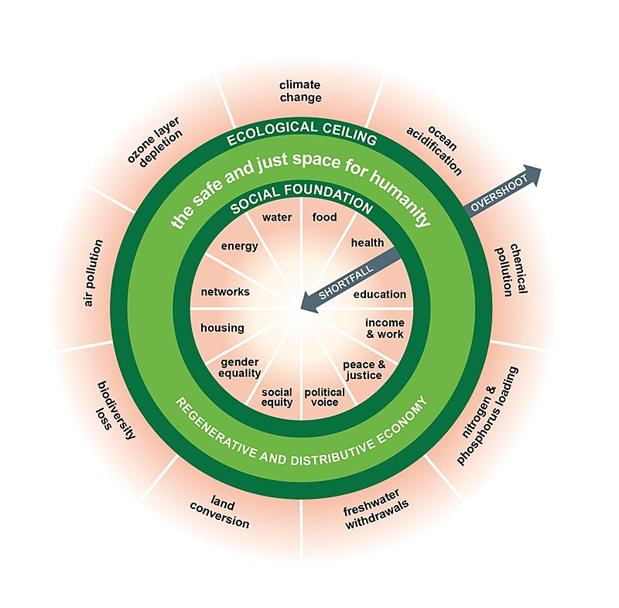

The model presents a visual representation of sustainable development, shaped like a doughnut.

In the doughnut economy visual framework, the inner boundary of the doughnut represents a social foundation, which outlines the minimum standards for human well-being. It includes elements such as access to food, water, healthcare, education, housing, and social equity. The aim is to ensure that no one falls below this social foundation.

The outer boundary of the doughnut represents planetary boundaries, which indicate the environmental limits within which humanity should operate to avoid damaging the Earth’s ecosystems. These boundaries include factors such as climate change, biodiversity loss, land use, freshwater use, and air pollution. The objective is to prevent overshooting these limits and causing irreversible harm to the planet.

The area between the inner and outer boundaries of the doughnut represents the “safe and just space for humanity.” The goal of the doughnut economy is to enable societies to thrive within this space, balancing human needs and planetary health. It calls for economic systems that are regenerative, distributive, and focused on improving well-being rather than pursuing unlimited growth.

Transforming the Doughnut Model of Social and Planetary Boundaries into a City-scale Instrument

Transforming the Doughnut model of social and planetary boundaries into a city-scale instrument involves contemplating the following 21st-century query: How can our city be “a home to thriving people in a thriving place, while respecting the wellbeing of all people and the health of the whole planet?”

This question can then be divided into four sub-questions to define the social foundations and ecological limits of the Doughnut model with regard to the local and global dimensions of the city. Those sub-questions are presented in the following graph, considering the city of Amsterdam as our case study, since it is one of the frontrunners in the implementation of Doughnut economics on a municipal level :

The four sub-questions outlined serve as four interconnected ‘lenses’, each one highlighting a different aspect of what it means to be a thriving city.

These four lenses use specific goals to define the Doughnut’s standards for social well-being and environmental sustainability, considering both local and global effects. The standards are then compared with relevant statistics to give a clear picture of how city life aligns with these goals. The approach enhances one’s insight into the city’s dynamics and their broader implications, facilitating a more nuanced assessment.

This inquiry encourages each city to embark on an examination of how it can flourish within the parameters of the Doughnut, taking into account the city’s specific location, context, culture, and global interconnections. The outcome of this exploration is what is referred to as the City Portrait.

The City of Amsterdam Leading the Way for Developing the First City Doughnut

Amsterdam emerges as a standout case study for the application of the Doughnut economics model at the city level, primarily owing to its proactive commitment to transformative urban development.

The Aspiration

Amsterdam aspires to maintain its status as a thriving and equitable city, ensuring a high quality of life for all residents and visitors without compromising the Earth’s natural boundaries. Focused on the principles of wellbeing alongside welfare, the city acknowledges the finite resources of our planet, necessitating a shift towards a more circular economy. Amsterdam is cognizant of the broader impacts of its consumption and production patterns, both within and beyond the city limits. Recognizing the potential of circular measures in achieving its climate goals, Amsterdam actively encourages citizens and visitors to be mindful of their personal impact. To fulfill its ambitious vision, the municipality is dedicated to transforming into a circular and climate-neutral city.

The Circular and Climate-Neutral City

Amsterdam has set forth the goal of becoming a circular city, aiming to reduce its dependency on primary raw materials by 50% by 2030 and achieve full circularity by 2050. Simultaneously, the city is committed to the objectives of the Paris Agreement, striving for a 55% reduction in CO2 emissions by 2030 and a 95% reduction by 2050 compared to 1990 levels. The aspiration is to be natural gas-free by 2040, aligning with the spirit of innovation and adaptation embodied in Amsterdam’s motto, “learning by doing”.

The City Doughnut Initiative

In pursuit of its circular and climate-neutral objectives, Amsterdam collaborates with Kate Raworth, through the Doughnut Economics Action Lab, working very closely with Biomimicry 3.8, Circle Economy and C40 Cities to develop the first City Doughnut. This initiative allows Amsterdam to envision and shape its future, providing a holistic framework for a circular economy. The Doughnut model serves as a powerful tool, offering insights into the intricate dynamics between material flows and social and environmental aspects. It helps prevent trade-offs in the implementation of circular economy strategies.

For instance, a policy aimed at reducing carbon emissions may inadvertently lead to job losses in certain industries. The Doughnut model can help policymakers weight these trade-offs and develop strategies to mitigate negative impacts while maximizing positive outcomes. The process involves a participatory trajectory, bringing together diverse stakeholders, including city officials and representatives from value chains, to mirror current targets with the Doughnut model, develop circular economy directions, align targets with ambitions, and validate directions with ground-level knowledge through a series of collaborative workshops.

Amsterdam’s commitment to the Doughnut model, in collaboration with Kate Raworth and Circle Economy, signifies a bold step towards a sustainable and regenerative urban future, where circularity and climate neutrality are at the forefront of city planning and development.

The Outcome

Workshops were organized with the various stakeholders and resulted in a set of seventeen directions that chart the way forward for embracing circularity within three Amsterdam’s key value chains: Construction, Biomass and Food, and Consumer Goods. Aligned with the prioritization strategy outlined in the “Amsterdam Circular: Evaluation and Action Perspectives” report, the city strategically focuses on those three key value chains, recognizing their potential to generate positive environmental and economic impacts.

The seventeen directions serve as the foundational pillars for fostering inclusivity and prosperity within Amsterdam. Going beyond environmental considerations, the seventeen directions address crucial social aspects such as equality and employment opportunities, embodying a holistic approach to urban sustainability.

This collective framework forms the groundwork for a comprehensive strategy propelling Amsterdam towards the realization of its inaugural City Doughnut.

The seventeen circular economy directions draw inspiration from past initiatives, incorporating insights from (inter)national policies, best practices, and recommendations, ensuring a well-rounded and strategic approach to transition Amsterdam towards a more circular and equitable economy.

Validation Through Participation

Crucially, each circular direction underwent meticulous design and testing through a participatory process involving over 50 representatives from the municipality of Amsterdam. This inclusive approach ensures that the directions are not just theoretical but resonate with the practical considerations of those involved in city governance. Furthermore, the validity of these directions was reinforced through extensive validation involving over 100 external stakeholders, including businesses, experts, and knowledge institutions.

Navigating Critiques: The Doughnut Model’s Reception in Amsterdam and Beyond

The emergence of Doughnut Economics in Amsterdam, a city known for its affluence and progressive values within a robust democratic nation, is noteworthy. However, proponents of this economic theory encounter resistance in certain quarters, exemplified by a Nanaimo, Canada city councilor who dismissed the model as a “very left-wing philosophy” demonizing business, growth, and development. It is crucial to dispel misconceptions, as the doughnut model does not universally oppose economic growth or development.

Kate Raworth, the model’s architect, acknowledges in her book that for low- and middle-income countries, substantial GDP growth is imperative to surpass the doughnut’s social foundation. However, the model emphasizes that such growth should be a means to achieve social objectives within ecological limits, rather than an isolated measure of success or a goal for affluent nations.

In a doughnut-inspired economy, fluctuations between growth and contraction are embraced, challenging conventional notions of continuous economic expansion.

Conclusion

Looking ahead, the imperative to transition towards a Doughnut Economy becomes increasingly urgent in the face of mounting environmental crises and social injustices. Cities must confront the reality of finite resources and ecological limits while striving to ensure a high quality of life for all residents. This requires concerted efforts from governments, businesses, communities, and individuals to rethink economic systems, prioritize sustainability, and promote social equity. While the road ahead may be challenging, embracing the principles of Doughnut Economics offers a beacon of hope for a more resilient, equitable, and sustainable future, not just for cities but for the entire world.

–

Sources

Collaboration between the City of Amsterdam, Circle Economy and Kate Raworth (2019) Building blocks for the new strategy Amsterdam Circular 2020-2025.

Guyon S. (2023) Circular Economy and doughnut economics.

Maldini, I. (2021) The Amsterdam Doughnut: moving towards “strong sustainable consumption” policy?

Nugent, C. (2022) Amsterdam Is Embracing a Radical New Economic Theory to Help Save the Environment. Could It Also Replace Capitalism?

Raworth, K. (2017) Doughnut Economics: seven ways to think like a 21st century economist, London: Penguin Random House

Raworth K, Krestyaninova O, Eriksson F, Feibusch L, Sanz C at DEAL; Benyus J, Dwyer J, Miller NH at Biomimicry 3.8; Douma A, ter Laak I, Raspail N, Ehlers L at Circle Economy; Lipton J at C40. (2020) The Amsterdam City Doughnut: A tool for transformative action

Tarnim, H. (2022) Doughnut Urbanism: An assessment framework for urban development through a Doughnut Economy perspective using the ‘Suikerzijde Noord’ as case.

Wahlund, M. & Hansen, T. (2022) Exploring alternative economic pathways: a comparison of foundational economy and Doughnut economics.