par Yiwen XU (EnvIM 2018)

In July 2017, the General Office of China’s State Council issued the Prohibition of Foreign Garbage Imports: The Reform Plan on Solid Waste Import Management, proposing that in 2018, China will ban the import of four classes of waste, including waste plastics from households, unsorted waste paper, waste textile materials, and vanadium slag. What is more, in April 2018, the Ministry of Ecology and Environment announced the addition of another sixteen types of solid waste, including waste hardware, and waste plastics from industrial sources, to the catalogue of prohibited goods. Since China was the largest solid waste importing country, with 56% of total market share in (Taylor, 2018), the world’s recycling economics has been upended as a result of the import ban. A large amount of solid waste destined for China was shifted to other developing countries, especially some Asian countries like Malaysia, Thailand and India. The volume of imported waste plastics for these countries increased by 113% in a year. Thailand recorded the highest growth with an increase of 875% for the import of waste polyethylene (Tan et al., 2018). While in developed countries, there was still a great amount of waste left in recycling centers, residential areas and piled up in mountains with nowhere to go.

Considering waste importation, China has a long history which began in the 1980s. The import amount of scrap materials was small before 1990, less than 1 million t/yr. After that, it steadily increased to 43 million t/yr in 2005 as a result of the huge demand for industrial raw material. However, with raising government awareness of imported waste management, more laws and regulations were created to provide standardization for this issue. Thus, the growth rate of imports was curbed after 2005. After the promulgation of the Regulations on Import Management of Solid Waste in 2011, the import amount even decreased, after reaching its peak at about 58.9 million t/yr in 2012. In 2015, the imported amount dropped to 47 million t/yr, of which the top three categories were waste paper (62.1%), waste plastics (15.6%) and waste hardware (11.0%), accounting for 88.7% of the total import amount (Liu, 2018).

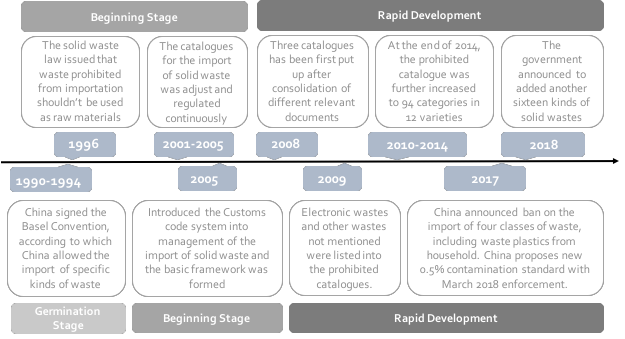

However, the above data were the legally imported amount, in compliance with laws and regulations, and did not contain waste, which has continued to increase. Between 2013 and the first half of 2015, there were 343 containers comprising 1.49 million t of waste seized by the Chinese Customs and from January to September 2018, 1.45 million t of imported waste has been seized (Li, 2018). China has provided instructions for importing waste from other countries, dividing the waste into three catalogues: importing without the restriction of customs processing, importing with the restriction of customs processing and prohibited from importation due to low energy-recovery efficiency and risk of environmental contamination. The three catalogues have been continuously adjusted and developed. In July 2009, the former Ministry of Environmental Protection updated the Catalogue of Solid Wastes Prohibited from Importation, adding electronic waste into the prohibited categories. At the end of 2014, the catalogue of prohibited was further increased to into 94 categories, within 12 varieties.

Nevertheless, . On one hand, the added waste categories of prohibited in 2017, such as waste paper and waste plastic, were the main components of waste imported to China, concerning nearly 70% of total amount (Liu, 2018). On the other hand, the implementation of regulations has been strengthened, coordinating with enhanced government supervision. The General Administration of Customs of China has launched campaigns on combating solid waste smuggling every year since 2006, such as “Green Fence 2013” and “Blue Sky 2018”. To further regulate import of waste, the Ministry of Environmental Protection conducted a campaign to inspect 1792 companies who involved in solid waste import and processing within China. It was found that nearly 60% of the inspected companies failed to meet the specified standard.

There is no doubt that China’s ban on importing waste is of dynamic adjustment, reflecting the firm determination of China’s sustained efforts on imported solid waste t. The measures taken at each stage were comprehensively coordinated with economic development, technical level and regulatory capacity. At the beginning of the 1980s, China focused its development strategy on economic construction. However, with weak foundation and insufficient production capacity, there was great shortage and strong demand of production materials. At that time, the consciousness of environmental protection in the whole society was very limited and vague in China. These years, with the rapid development of economy and society, Chinese government and the public have been more aware of the importance of coordinated development of environment and economy. Therefore, imported waste management has also been changing with times. In 2015, the Chinese central government initiated a strategic plan, Made in China 2025 to upgrade Chinese manufacture industry. The goal of the plan is to increasing the proportion of domestic components and materials to 40% by 2020 and 70% by 2025 in some sectors, such as automotive and aviation. The import ban would push the producers in these industries to use raw materials from local sources. What is more, in March 2017, the General Office of the State Council announced the Implementation Plan of the Domestic Waste Classification System, proposing that by the end of 2020, the relevant laws, regulations and scalable waste sorting system should be established and the utilization rate of domestic waste should be more than 35% in the pioneer cities. It complements the import ban to improve the domestic resource recovery capabilities. Given the facts, China is getting serious about environmental quality and won’t be backing down the import trade.

Why was waste being imported?

Profits from sectors have kept the operation of the import supply chain going for nearly 30 years. For developed countries, waste management entails high costs, due to stringent environmental standards and high labor costs. It has been shown that waste treatment costs range from $400 to $1,000 per ton in developed countries, while the cost of shipping to China, even with freight charges, was only $10 to $40 per ton (Feng, 2018). Therefore, exporting waste to China was undoubtedly an economically sound option.

On the other hand, since the reforms and program of opening up in 1978, raw materials have been highly demanded to provide support for China’s rapid development. Therefore, the imported waste plastics, waste paper, and metal materials with high recycling value were supplements to insufficient resources for such as electronic products and plastic recycling. Moreover, compared to waste from domestic factories and recycling centers, which were not well sorted, imported materials were of better quality and easier to proces according to the material recycling facility (MRF) operators (Wang, 2018). In addition, it also brought tangible economic benefits to Chinese enterprises. Due to the less developed framework for waste management and because of weak environment awareness, there was little standardization of waste recovery and reuse. For example, during recycling of electronic waste, not only could a large number of precious metals, such as copper, aluminum and tin be obtained, but also some reusable components were reintegrating the market and were widely welcomed because of their high quality. According to the Plan of Developing Renewable Resources Industry in Guiyu Town, “2.2 million tons of waste electronics, hardware and plastics were recycled and processed in Guiyu, Guangdong, in 2010 and the output value was as high as 5 billion yuan.”(Wang, 2018)

What harm did imported waste bring?

Importing waste also caused critical environmental challenges. Many recycling companies did not have pollution control facilities causing serious pollution discharges, damaging the local ecological environment. For example, imported electronic waste is non-degradable and will release a large number of toxic and harmful substances. It was shown that in Guiyu, the local atmosphere and soil was severely contaminated by PCDD/F (dioxins that cause cancer) due to poor manual dismantling and recovery technology in family workshops (Wong et al., 2007). Moreover, some imported material also carried colorless and odorless radioactive pollutants, which are difficult to detect and be treated .

After nearly 40 years of rapid development, China’s economy has become the second largest in the world, but the demand for importing waste for raw material has been declining during these years. At present, many industries in China, including iron and steel, glass, electronic products, and plastic products, all occupy a high market share in the world but with various degrees of over-capacity, causing low profits for businesses. At the same time, the unstable quality of imported solid waste determines that it can only produce of relatively low added value. However, a large number of such products has lowered the price of high added value products, worsening the business environment and disrupting market order.

The effect on developed countries

The ban on imports of waste from developed countries have taken effect since the beginning of 2018. With no suitable strategies in place for treating the extra unexpected waste, most developed countries who used to transfer their recyclables to China have experienced notable effects as a result. In March 2018, the U.S., the E.U., Japan, Australia, Canada and South Korea showed their concern about the import ban at the WTO’s Council, insisting that the import restrictions on recycled commodities had changed so fast that the industry could not adjust to it, causing a fundamental disruption in global supply chain. However, to deal with the current situation, they were forced to seek sustainable alternative management solutions.

The U.S. exported nearly one-third of its recyclables, of which almost half was transported to China (Burns, 2017). According to the survey of the situations in 50 states of the U.S. after import ban conducted by Waste Dive, states like Hawaii and New Mexico, which had tenuous recycling markets, are now stuck and are facing with an uncertain future. Some states have granted a small number of disposal waivers for waste, while others believe that citizens should pay more for waste disposal. Recycling costs in Braintree, Massachusetts, have increased by more than ten times, and local officials fear that if costs continue to rise, local governments will most likely be forced to suspend other public services such as education or mass transit. However, in the south, there was less impact due to more local markets (Rosengren, 2017).

The UK’s recycling industry also did not coped well with the import ban since nearly 40 % of its plastic waste was previously imported to China (McNeice, 2018). In response to a public watchdog groups that said that the government has not taken much actions, the UK’s government has committed to overhauling its waste recycling system and stated that all avoidable plastic waste will be eliminated within 25 years. What is more, the House of Commons also set up a special investigation team to introduce measures against impacts of the import ban. One well-known proposal was the ‘latte levy’ of 25 pence on every cup used to tackle the pile-up of disposable coffee cups.

While in South Korea, the government has been struggling to avert the plastic waste chaos. The government has never intervened in the waste recycling market before, as it was handled by private enterprises. As soon as the import ban came out in China, a in the price of plastic waste has appeared, which directly lowered the profits of waste recycling companies. Therefore, in April 2018, these companies stopped waste collection services for plastic bags, resulting in waste build-up and increased complaints and criticism. Facing such a chaotic situation, the Korean government finally responded to the public saying that it would launch a subsidy policy to stabilize markets afflicted by decreasing waste exports. Although some recycling companies decided to resume collection service due to government’s compensation, there was still much uncertainty regarding the operation of the plastic recycling system in the future.

The waste situation in other developing countries

After Chinese import ban, some other developing countries, as a new market, received much more waste from developed countries than before. In 2018, the volume of imported waste plastics for southeast Asian countries, such as Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam, increased by 113%. Thailand recorded the highest growth with an increase of 875% for the import of waste polyethylene (Tan et al., 2018). However, these countries have begun to say “no” to the import of solid waste since the new import amount is overloading their capacity.

In July 2018, the Malaysia’s government cancelled the permits for importing plastic waste of 114 factories because it was found that more and more illegal plastic recycling factories, driven by profits, have been opening, which has seriously damaged the environment. From January to July of the same year, Malaysia imported more than 450,000 tons of plastic waste, compared with less than 320,000 tons in 2017 and only 168,000 tons in 2016. Recycling and reusing these imported waste can bring billions of dollars to Malaysia, but the country does not have the ability to deal with this garbage at present. Recently, the government has been considering stricter licensing rules for waste recycling companies, requiring them to meet environmental standards and operate only in specific industrial zones, which actually is good for Malaysia’s imported waste management

Once, at the Kailai Port, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, there was a backlog of 8,000 containers of imported foreign waste, one third of which had not yet gone through customs after 90 days, causing port congestion. To avoid similar incidents from occurring again, at the end of July 2018, the government announced a moratorium on importing waste plastics, stopped issuing new import permits, and would severely of waste paper, waste plastics and waste metals.

Also in Thailand, with the increasing amount of imported solid waste, the Ministry of Environment decided that Thailand would announce a ban on imports of 432 kinds of electronic waste, including circuit boards, old televisions, radios, etc. within the next six months, and finally the prohibition on all plastic waste would be implemented within three years.

New market

In November 2017, China has further proposed a 0., up from 1.5%, for paper and cardboard, plastics and others apart from 1% that will be allowed for non-ferrous metals. The new standard will be extremely difficult to comply with, especially with only until March 2018 to hit the requirement, according to the Recycling Association. However, some companies have already found new opportunities behind the restrictions. On one hand, many MRFs have added labor and invested in new technology to improve the quality of recyclable waste. In May 2018, the Hong Kong Nine Dragons Paper (Holdings) Ltd. purchased factories in Wisconsin and Maine from a Canadian company for $175 million. Brian Bolan, vice president of ND Paper, said the factories would produce paper and packaging materials in North American, and also they could process waste paper into pulp which can be used as raw material and transport it to China. Moreover, many Nigerian recycling exports believed that the import ban in China is good for their country to develop recycling industry. According to them, Nigerian has been capable of handling waste processing and all the recyclables gathered should be processed right there in Africa. On the other hand, agreements were made that current economic structure of recycling needs to be understood. Through investigation on every part of the waste supply chain, it will help to expand the domestic market, contributing to the creation of new systems of waste management and offering job opportunities.

What to do next?

As more and more developing countries are forced to promulgate the ban on importing waste, large amounts of solid waste will be piled up. Although incinerators and landfill will take some of the surplus waste, the capacity of both is limited and overcapacity of treatment facilities will bring poorly management and environmental contamination. As a matter of fact, many countries have realized that excessive waste needs to be recycled or disposed in a cleaner way and some take it as an opportunity to call for the further development of recycling industry. Therefore, suitable strategies and innovations for taking full responsibility for waste generation throughout its life cycle should be embodied and implemented for dealing with this unexpected waste.

Raising public awareness is essential. It is important to change living habits and reduce the use of plastic products at the source. Eric Solheim, the Executive Director of UNEP, pointed out that “China’s ban on imports of plastic waste should be a signal for developed countries to strengthen recycling and reduce unnecessary products such as plastic straws. (Doyle, 2018) According to Solheim, Americans consume nearly 0 straws per person a year, an unnecessary habit, which produces a lot of waste plastics. He also revealed that some companies, including Coca-Cola, Nestle and Dannon, are taking actions to improve the recycling efficiency of plastic products and to replace conventional plastics with biodegradable packaging materials.

Improving waste sorting technology is necessary for meeting Chinese import standards. An important reason why China was reluctant to accept foreign waste was due to the serious contamination, which increased the difficulty of waste sorting and its environmental risks. It was stated by the Chinese General Administration of Customs that pollutants in solid waste would infiltrate into soil and drinking water without proper treatment, thereby endangering the ecological environment. In order to meet this standard in China, some waste recycling centers abroad have begun to increase their manpower and upgrade their technologies and equipment.

Last but not least, establishing domestic markets and enhancing the capacity of self-recycling can also play a significant role. The North American Solid Waste Association recommended that the U.S. explore its domestic market as much as possible to reduce its dependence on the Chinese market. In order to minimize waste generation, the EU is launching a new plastic strategy, where products, secondary materials and raw materials will be recycled domestically as long as possible. To this end, the EU has introduced relevant laws to limit the consumption of plastic bags and other plastic products in member countries. The ‘plastic tax’ proposed by Quentin Odinger, the EU budget commissioner, is likely to become part of the EU’s new regulatory framework.

To conclude, China has been working on imported waste management since the 1990s. Due to the reforming of industrial structures, there have been increasing varieties of waste that were prohibited from being imported and those that were still allowed to enter the country had to meet stricter contamination standards. The import ban has had immense territorial consequences and contributed to a transformation of the geography of waste management, transforming possibly its scale of expansion from an international level to an increasingly more local scale.

References:

Burns J , PROFITA C . (2017, December 9). Recycling Chaos In U.S. As China Bans ‘Foreign Waste’. https://www.wbur.org/npr/568797388/recycling-chaos-in-u-s-as-china-bans-foreign-waste

Doyle A . (2018, January 29). INTERVIEW-China’s plastic trash ban is spur to recycle – UN Environment. https://af.reuters.com/article/africaTech/idAFL8N1PO5DV

Feng H . (2018, March 13). Waste ban forces unlicensed recyclers to clean up act. https://www.chinadialogue.net/article/show/single/en/10438-Waste-ban-forces-unlicensed-recyclers-to-clean-up-act

Li X J . (2018, September 14). China has verified 1.45 million tons of smuggled foreign garbage in 2018 and will continue to crack down severely in the future. http://www.chinanews.com/sh/2018/09-14/8627203.shtml

Liu J G . (2018, May 27). The significance and implications of ban on importing foreign waste to waste sorting in China. http://www.h2o-china.com/column/892.html

McNeice A . (2018, July 23). UK to overhaul waste export practices following China ban. http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201807/23/WS5b55f35da31031a351e8fa06.html

Reynolds M . (2008, January 22). China environment pollution recycling. http://www.epa.eu/environment-photos/environmental-pollution-photos/chinese-migrant-workers-sort-through-industrial-and-household-waste-at-a-recycling-centre-in-beijing-china-photos-01230267

Rosa A , MASSOLA J . (2018, October 22). Malaysia bans waste imports as Australia battles recycling crisis. https://en.mogaznews.com/World-News/1054926/Malaysia-bans-waste-imports-as-Australia-battles-recycling-crisis-mogaznewsen.html

Rosengren C . (2017, November 15). Market effects vary by state, but widespread agreement is recycling needs to change. https://www.wastedive.com/news/market-effects-vary-by-state-but-widespread-agreement-is-recycling-needs-t/510994/

Tan Q , Li J , Boljkovac C . Responding to China’s Waste Import Ban through a New, Innovative, Cooperative Mechanism[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2018, 52(14):7595-7597.

Taylor M . (2018, January 16). Southeast Asian plastic recyclers hope to clean up after China ban. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-asia-environment-waste-plastic/southeast-asian-plastic-recyclers-hope-to-clean-up-after-china-ban-idUSKBN1F504K

Wang X C . (2018, Autumn 29). One year after import Ban, China’s Decision Impacts Global Solid Waste Treatment System. https://m.jiemian.com/article/2422292.html

Wong M H , Wu S C , Deng W J , et al. Export of toxic chemicals – A review of the case of uncontrolled electronic-waste recycling[J]. Environmental Pollution, 2007, 149(2):0-140.