Article de Clémentine Pélissier (MS EnvIM 2023-24)

Introduction

We can consider that the story of textiles (defined as a material that can be woven, divided into yarns that can be woven [1]) goes back to 9000 before JC, in Mesopotamia with sheep and goat hair. Quickly followed by the development of cotton in Asia (5000 BC) or linen in Egypt (3000 BC) [2].

This quickly becomes a matter of trade and business, notably with the development of major routes like the famous Silk Road to import the precious textile from China back to Europe. It took on a whole new dimension from the 19th century with the apparition of spinning industrialization, allowing an efficient transformation of the raw materials in textile for much lower costs, leading to the development of a far bigger economy.

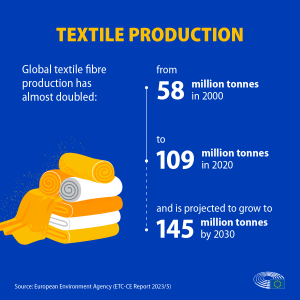

The discovery of synthetic fiber around the 1930’s further transformed what we could call from then the textile industry. Textiles made from nylon, polyester, or acrylic, petrochemical derivatives, rapidly spread representing huge quantities of production. With the emergence of prêt-à-porter at the same period, the textile industry faces a real booming leading from the 2000’s to the phenomenon of “fast fashion”, which has been constantly growing since then.

The Fast Fashion describes a new way of consumption and production, with a constant provision of new styles at low prices, leading to buying two times more clothes, that are kept half as long. This means 100 billions of clothes sold in 2016, representing in average 9.5 kg of clothes per inhabitant in France and 26 kg in the UK [3].

Beside the ethical issues that such consumption mode could raise, the environmental impact of textile industry today is huge, not to mention the social issues implicated.

How are textiles produced ?

To better assess the various impacts of the textile industry, we first need to go back to the process of textile production. There is indeed a great variety in terms of methods and composition. [4]

The process starts with the production of raw materials. They can be first of natural origin, either from plants, mostly from cotton, but also linen, hemp or bamboo cultures, from which extract cellulosic material can be extracted, or from animals. Animal textile materials are animal or insect hairs, feathers, skins or secretions. The main materials are based on proteins, such as wool from various animals (mostly sheep) and silk for the most common. But the raw materials can also come from synthetic fibers, such as polyester, polyamide, or polyacrylic. They are made by polymerization of monomers sourced from fossil oil feedstock.

The fibers are then spined into yarn, further transformed into fabrics through different methods. Depending on the type and the purpose of the fabrics, the materials can undergo several pre-treatments before dying and printing. All the transformation phases require therefore various chemicals, lubricants, solvents, adhesives or binders as well as many washing or bleaching steps.

The textiles can from then be manufactured into the product wanted (pants, shirts, carpets, curtains,…) and transported to the places where they are to be sold.

How are our closets impacting the planet ?

According to the European Environment Agency, in 2020 textile consumption per person in the EU required 400m2 of land, 9m3 of water, 391kg of raw materials, and caused a carbon footprint of about 270kg. In fact, each step in the life cycle of a textile represents its own set of impacts. [5]

- Raw material

If we go back to the production of raw material, the production of cotton, used in 25% of the t-shirts we wear, is very harmful for the planet. Being a fragile type of crop, cotton growing requires most of the time massive use of pesticides. Approximately one fourth of the pesticides used in the world would be dedicated to cotton cultures, biologic cotton representing only 1% of the surface dedicated to this crop. Cotton cultivation means also very intensive resource usage, especially water. A single cotton t-shirt represents, over the whole manufacturing process, 2700 L of water, equivalent to the amount of water consumed by a French person over 3 days in average [3]. This is not to mention the land-use all these crops represent.

When looking at animal fibers, livestock represent the big emissions of greenhouse gases, especially for wool or leather, alongside with the consumption of resources to feed the animals. In the specific case of furs, coming from hunting and not breeding, the impact is more in terms of biodiversity, with the decrease of species, notably endangered species. The matter of animal welfare is also naturally raised with any kind of intensive livestock. Certain treatments for parasites in the wool for instance can be very painful for the animals, not to mention the type of fibers that require the death of the beast (leather or fur) [6].

Finally when the fabrics are complemented with synthetic fibers such as polyester, the share of GHG emissions increases furthermore, due to the fossil resources used to produce them. [3]

- Manufacturing

The transformation step, from fibers to fabrics, implies in any case the usage of chemical, mostly toxic, substances [7]. Even though these chemicals were not produced to be “bad”, we can question if the adverse effect overcame the intended purpose. These chemicals range from flame retardants for children’s clothes mostly, to some heavy metals as lead and chromium used to stabilize colors in the dying process, or PFAS materials (fluoropolymers) known for their resistance to water, oil, heat and stains. Such chemicals and others that can be found in our clothes are first major pollutants of water, but also represent health risks, from skin irritations to hormone disruption or even probable carcinogens. These health impacts are most of the time not immediate but remain a risk, especially after prolonged or extensive exposure. There are some already existing regulations in Europe, but they don’t apply yet to any country of production.

Therefore, the user can be concerned by these issues, but the most exposed one remain the workers. Indeed, with the delocalization of manufacturing activities, the textile industries are always looking for more low-cost labor abroad. The employees are most of the time working in very poor conditions, without social protection and for very low wages [8].

The big textile and clothing companies kept relocating the manufacturing activities depending on where the lowest monthly salary could be found, moving from China to South Asia countries and more recently Ethiopia. Awareness around these topics is raising, notably with the reveal of more and more scandals such as the production of Chinese cotton derived from forced labor of Uighurs, a Muslim minority repressed by Beijing [9]. Even though the behavior of textile industry is now more observed, and conventions are being signed, it remains difficult to reach international agreements and control that the production of all imported textiles is respecting the norms.

- Transport

As a consequence of the repartition through the world of places of production, manufacturing and consumption, our clothes are travelling a lot. With 50% of the clothes sold in France coming from China, they can cross up to 65000 km over the whole process. This naturally adds to the share of GHG emissions: overall, the fashion industry is estimated to be responsible for 10% of global carbon emissions. [3]

- Usage

At the user stage, despite the health risks from various chemicals previously described, the main issue remains the cleaning. Dyeing and finishing products contained in the textiles represent a major source of clean water pollution. Added to this is the problem of microfibers, and more specifically microplastic. Laundering synthetic clothes accounts for 35% of primary microplastics released into the environment. A single laundry load of polyester clothes can discharge 700,000 microplastic fibers that can end up in the food chain. [10]

- End of life

When finally, we decide to get rid of our clothes, the reflex is not yet recycling. Indeed, used clothes represent in Europe about 4 million tons per year of wastes, 80% of that going directly to landfills. Less than half of used clothes are collected for reuse or recycling, and only 1% of used clothes are recycled into new clothes.[11]

New options to be eco-fashion

Then the big question is: how to decrease the impact of clothes and textiles industry on the environment?

When considering the dramatic reverse side of Fast Fashion, it seems the most direct action would be a change in consumption habits. The public awareness regarding the environmental and social impacts is generally growing, pushing the consumers to better think its choices. However, it remains difficult to change habits that are very much linked to a matter of trends and modes, constantly evolving, and spreading across the world at an unprecedent speed.

Yet, the consumers behavior should tend toward “Slow Fashion”, targeting clothes of better quality that last longer, selecting more sustainable options, and naturally, buying less. Promoting these ideas, clothes market witnessed for instance the rebirth of thrift shops, second-hand products answering the trend of “vintage style”. In the same model of “back to basics”, new kind of offers are growing on the market, promoting clothes entirely made of reused fabrics (ex: La Vie est Belt [12]) or selling products only to order (ex: Asphalte [13]) to limit overproduction as well.[14]

To tackle the issue from a broader angle, changes need to be made from the production level, implementing a “circular fashion”. The products need to be designed in a way that would make re-use and recycling easier, while using resources more efficiently, to increase the life cycle of textiles and decrease the impacts. Implementing such a change requires however a comprehensive approach, involving various stakeholders. This becomes then a choice from the companies. [15]

To promote and incentivize this kind of initiatives, policy makers play a key role. European countries are putting in place extended producer responsibility schemes, alongside with more regulations and directives, notably since March 2022 with the Eco-Design directive for Sustainable Products Regulation [16].

This directive creates a concrete framework to set eco-design requirements for products, including textiles. The overall targets are part of the EU strategy for sustainable and circular textiles, implementing the commitments of the European Green Deal, the Circular Economy Action Plan and the European Industrial Strategy [17]. On top of that, under the Waste directive from 2018, EU countries will be obliged to collect textiles separately by 2025. To finally informed the customer on their commitments, businesses can also apply the EU Ecolabel to items respecting a set of ecological criteria [11].

Answering these new objectives, customers are offered more and more sustainable textiles appearing on the market. First coming from organic cultures, such as organic cotton, grown without the use of harmful pesticides and synthetic fertilizers. This appears as an eco-friendly alternative that protects the health of farmers and preserves soil quality; however, the important need of water remains unchanged. Several recycled fabrics are also developed: by using post-consumer wastes like plastic bottles or textile wastes, they reduce the demand for virgin materials and minimize wastes going to landfills [18].

Even more technological solutions can be found today, such as Tencel™ or bio-manufactured fabrics. Derived from sustainably sourced wood pulp, Tencel™ fibers are produced using a closed-loop process, meaning that the solvents and water used during production are recycled, reducing waste and energy consumption [19]. Scientists are also exploring the possibilities of growing textiles using living organisms like bacteria or fungi [20].

These bio-manufactured fabrics have the potential to be biodegradable, minimizing waste and creating a circular economy. In the same idea, bio-based or plant-based fabrics are rapidly growing, made from biological material such as sea-weed, corn and sugar cane [21]. This is specifically the case when looking for alternatives to classic leather.

The case of leatherThe leather is made from animal skin, most commonly of cows, but one can also find leather from deer or goat for instance, as well as “exotic” skins such as crocodile or snake. [6] Most of the skins used in the production of leather are actually by-products from the food industry, except for some type of exotic products where dedicated breeding is required. However, skins issued from beef production are often stained or scratched and therefore unusable for haute couture brands. This is why only 2 to 5% of skins are properly recycled in France. [22] As an expensive material, imitations made mostly of synthetic fibers (such as polyurethane) have been developed to offer an alternative to more modest populations, especially in the context of fast fashion where customers are encouraged to buy more and more often in poorer quality. [23] Therefore, the environmental impacts remain the same as the ones mentioned before: fossil fuel as a raw material, toxic chemicals used in the fabrication process, lower quality leading to a quick renewal, and so on. The real cowhide as by-product of food industry appears in this context as a far more sustainable solution, offering a first step towards circular fashion. Moreover, this material is obtained through less chemical and transformative processes, is repairable, and very resisting when taking care of. [6] However, the topic of animal welfare can remain a blocking factor, especially for vegan movements. Hopefully some other alternatives more ecological are existing today: from grape pomace (wine industry waste), with the Vegea® and TannGreen® brands; from apples (food industry waste), with the Apple Skin® brand; from pineapple (fibers extracted from the leaves of pineapple harvesting waste from the agri-food industry), with the Piñatex® brand; or also with cactus (Prickly Pear) with Desserto®, and the list goes on. But even these sustainable products can suffer from a heavier carbon footprint due to the place of raw material production implying further transport (e.g., cactus in Mexico), or the mix with other products making them less repairable (e.g., polyurethane lining), or even some chemical treatments required in the production process. |

Conclusion

The case of leather is overall a good example of our bad habits of consumption in terms of clothing, and the proof that alternatives exist, and that such innovations keep on flourishing. However, these alternatives are not sufficient alone and improvements are needed at all levels of clothes life cycle.

While more stringent directives and regulations are slowly being instituted at International and European level, the objective for us as individuals is about first choosing the right quality, second repairing, and third reusing, all this to buy less often and less quantity. So before buying a new jacket for the coming season, let’s re-custom an old one abandoned at the back of the wardrobe, or check at the thrift shop downstairs to find a rare gem !

–

Bibliography

[1] Le Robert, ‘Textile – Définitions, synonymes, prononciation, exemples’, Dico en ligne Le Robert. Available: https://dictionnaire.lerobert.com/definition/textile. [Accessed: Nov. 19, 2024]

[2] Quand la planète s’habille – Le Dessous des Cartes | ARTE, (Mar. 20, 2021). Available: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1XmhVgTr4Y0. [Accessed: Nov. 15, 2024]

[3] Black Friday : Pourquoi s’habiller pollue la planète, (Dec. 13, 2018). Available: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3DdU7c66E9g. [Accessed: Nov. 15, 2024]

[4] Chemsec, ‘Get familiar with your textile production processes | Textile Guide’. Available: https://textileguide.chemsec.org/find/get-familiar-with-your-textile-production-processes/. [Accessed: Jan. 06, 2024]

[5] European Environment Agency, ‘Textiles’, Jun. 02, 2023. Available: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/topics/in-depth/textiles. [Accessed: Jan. 07, 2024]

[6] Derenne Elsa, ‘Laine, cuir, soie & co : tout savoir sur les fibres textiles animales’, écoconso, Nov. 15, 2023. Available: https://www.ecoconso.be/fr/content/laine-cuir-soie-co-tout-savoir-sur-les-fibres-textiles-animales. [Accessed: Apr. 25, 2024]

[7] J. Wilson, ‘Toxic Textiles: The Chemicals in Our Clothing’, Earth Day, Nov. 04, 2022. Available: https://www.earthday.org/toxic-textiles-the-chemicals-in-our-clothing/. [Accessed: Apr. 25, 2024]

[8] D. Enrico, ‘Workers’ conditions in the textile and clothing sector: just an Asian affair?’.

[9] P.D with AFP, ‘Travail forcé des Ouïghours en Chine: l’industrie textile patauge’, BFM BUSINESS. Available: https://www.bfmtv.com/economie/travail-force-des-ouighours-en-chine-l-industrie-textile-patauge_AD-202101190037.html. [Accessed: Apr. 25, 2024]

[10] Y. Cai, D. M. Mitrano, M. Heuberger, R. Hufenus, and B. Nowack, ‘The origin of microplastic fiber in polyester textiles: The textile production process matters’, Journal of Cleaner Production, vol. 267, p. 121970, Sep. 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.121970

[11] European Parliament, ‘The impact of textile production and waste on the environment (infographics)’, Dec. 29, 2020. Available: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/headlines/society/20201208STO93327/the-impact-of-textile-production-and-waste-on-the-environment-infographics. [Accessed: Jan. 07, 2024]

[12] La Vie est Belt, ‘Notre mission’, La Vie est Belt. Available: https://lavieestbelt.fr/pages/notre-mission. [Accessed: Nov. 19, 2024]

[13] Asphalte, ‘Notre mission’, Asphalte. Available: https://www.asphalte.com/f/pages/notre-mission-f. [Accessed: Nov. 19, 2024]

[14] Water Footprint Calculator, ‘How to Dress Greener: 5 Reasons to Shop at Thrift Stores’, Water Footprint Calculator. Available: https://watercalculator.org/footprint/how-to-dress-greener/. [Accessed: Nov. 19, 2024]

[15] Ellen MacArthur Foundation, ‘A New Textiles Economy: Redesigning fashion’s future’, Nov. 28, 2017. Available: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/a-new-textiles-economy. [Accessed: Nov. 15, 2024]

[16] Mortensen Lars, ‘How to make textile consumption and production more sustainable?’, Mar. 15, 2023. Available: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/newsroom/editorial/how-to-make-textile-consumption-and-production-more-sustainable. [Accessed: Apr. 25, 2024]

[17] European Commission, ‘Textiles strategy’, Sep. 27, 2024. Available: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/strategy/textiles-strategy_en. [Accessed: Nov. 19, 2024]

[18] W.ell Fabric, ‘Recycled Fabrics: 4 Popular Types in the Fashion Industry’, Jul. 25, 2023. Available: https://wellfabric.com/popular-recycled-fabrics/. [Accessed: Nov. 19, 2024]

[19] Tencel Company, ‘About TENCELTM Lyocell and Modal Fibers’, TENCELTM. Available: https://www.tencel.com/. [Accessed: Nov. 19, 2024]

[20] Jamie Priest, ‘Sustainable textiles made from fungi’, Mar. 23, 2022. Available: https://cosmosmagazine.com/technology/materials/sustainable-textiles-fungi/. [Accessed: Nov. 19, 2024]

[21] Morrama, ‘Alternative textiles’, A Sustainable Design Handbook. Available: https://www.sustainabledesignhandbook.com/alternative-textiles. [Accessed: Nov. 19, 2024]

[22] ‘Que devient le cuir des bovins français ?’, Web-agri.fr. Available: https://www.web-agri.fr/vaches-allaitantes-pmtva/article/864101/a-la-decouverte-de-la-filiere-cuir-entre-luxe-et-surabondance. [Accessed: Nov. 19, 2024]

[23] Marion Mesbah, ‘C’est quoi le simili cuir ? – Définition – Marques de France’, Mar. 13, 2023. Available: https://www.marques-de-france.fr/definition/simili-cuir/. [Accessed: Nov. 19, 2024]