article par Matteo Cassinelli (EnvIM 2019)

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is an ambitious program of investments aimed at improving connectivity, national cooperation, integration of markets and income of BRI countries. Since it was announced by the Chinese government in 2013, the initiative has risen much hope and concern. Many have seen growth and development possibilities while others have urged caution over the risks related to the projects, especially for developing countries.

Broadly speaking, it is an economic plan designed to open up and create new markets for Chinese goods and technology at a time when the economy is slowing, to help exports, and to transfer factories to other countries in Asia where production costs are lower, along the route of the historic Silk Road.

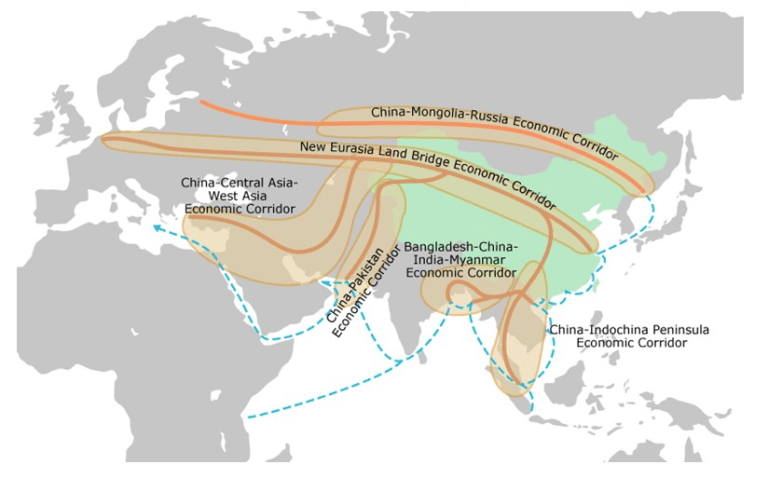

The BRI includes the Silk Road Economic Belt connecting China to South Asia and Europe, and the New Maritime Silk Road linking China to South East Asia, the Gulf Countries, North Africa, and Europe. Six main economic corridors can be identified (Figure 1). While the scope of the program is still unclear, China is spending roughly $150 billion a year on the project (J.P., 2017) and official data states that 125 countries have signed collaboration agreements with China as of March 2019 (World Bank, 2019). Total BRI project volume is estimated at $1 trillion (Hillman J., 2018). All countries are welcome to join the initiative so that some of them are located in Latin America or Africa noncoastal areas. In 2017, corridor economies accounted collectively for about 40% of the global merchandise exports, almost five times higher than in 2000, and almost 40% of China’s overall merchandise export (World Bank, 2019).

During the second bi-annual Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation on April 25-27, 2019, China assured the world that the BRI will be in accordance to the “Green Investment Principles for the Belt and Road” call promoting environmental friendliness, climate resilience, and social inclusiveness under new BRI investments. These principles are aligned with the goals of the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the Paris Agreement. While complementary policies have been proposed to meet these conventions, there is little evidence of project guidance or implementation.

Large infrastructure programs of the kind have historically had detrimental impact and immense implications for the environment. For instance, the huge dam project in Indonesia financed by the Bank of China and Sinohydro, China’s hydropower authority, has been largely criticized for endangering the only known habitat of the world’s rarest great ape (Gokkon B., 2018). WWF estimates that the backbone BRI projects, not considering various side projects, directly affect 265 threatened species.

This article aims to identify the greatest opportunities and risks related to the largest infrastructure project of all time, providing some recommendations to cope with the multitude aftermaths of such a massive plan while reaching its full potential.

Figure 1: BRI economic corridors spanning Asia, Europe and Africa.

Figure 1: BRI economic corridors spanning Asia, Europe and Africa.

Source: Losos E. et al., 2019.

Opportunities and Risks outline

BRI initiative carries many economic opportunities related to its huge extent and scope. BRI economies account for one-third of global GDP and trade. This last is expected to increase corridor economies income between 1.2 and 3.4% (World Bank, 2019). Poverty ratio in some of these countries is very high with considerable share of the population living in condition of extreme poverty, such as Kenya, Uzbekistan, Djibouti and Laos. If BRI initiative is successful, it may benefit a significant number of people facilitating, for instance, social integration and job opportunities creation. Sadly, international trade agreements do not necessarily have positive impact on people welfare’s, particularly on those layers of the population not being included in these kind of exchanges. On the contrary, it may kill local activities, create some new forms of path dependence and degrade local condition of living provoking localized welfare loss.

The initiative is also addressing large unexploited potentials when considering trade and foreign direct investments (FDI) in the corridors. BRI countries have been increasingly integrated and connected to the rest of the world and have seen their contribution to global exports nearly doubled in the last two decades. However, few economies are responsible for most of these exports, with China having the lion’s share. Intergovernmental macroeconomic policies and communication mechanisms between corridor countries are necessary to coordinate the integration in the global market.

According to the World Bank, in 2017, BRI economies received around $600 billion from FDI and, since the global financial crisis, they have absorbed almost 35% of the global FDI flow. However, developed countries have accounted for 80% of FDI inflows and 90% of FDI outflows. In low-income countries such as Bangladesh, Pakistan, Nepal, Uzbekistan, Timor-Leste, Bhutan, Brunei, and Kenya, FDI accounted for less than 1% of GDP but they are expected to see an increase up to 7.6% due to new connections.

BRI initiative has also been designed to open up and create new markets for China while boosting its exports. To ship goods from China to Central Europe by sea currently takes about one month, while it requires half of the time by train, although costs are higher and cross-border trade is more complicated. Once BRI projects will be operating, travel times along economic corridors will decline and network capacity will increase. International cooperation and harmonized standards for infrastructure are major objectives of the program to reduce policy barriers, cross-border restrictions, and delays since the value of a country’s investment would increase by connecting its network to that of another country.

However, all these potential gains come with significant socio-environmental risks, always linked to large infrastructure project of this kind. They might include environmental degradation, corruption, social tensions, gender-based violence, child labor, and might be particularly significant in countries with weak governance. BRI investments must be carefully considered while high environmental standards and mitigation strategies must be integrated to minimize medium and long-term negative effects.

The limited publicly accessible information suggests that the majority of BRI contracts have been allocated to Chinese suppliers and contractors, mainly financed by China’s state-owned banks. The Center for Strategic and International Studies analyzed a sample of BRI projects for which data were available and estimates that more than 60% of Chinese-funded BRI projects have been assigned to Chinese firms (World Bank, 2019). The process for selecting firms is still not clear due to a lack of transparency. Corruption can vary along the corridors according to the quality of domestic institutions. Therefore, international cooperation is once again fundamental to enhance open and transparent public procurement while monitoring services would limit corruption.

Moreover, China is promoting its own economic interests over those of other countries and their environmental health. Countries with significant natural resources may have access to extended loans that can be repaid with oil and ores. China has been criticized to use “debt-trap diplomacy” to establish advantageous power relationships and extract strategic concessions. For instance, in 2010 a Chinese state-owned corporation has been paid $1.5 billion to build a new port in Sri Lanka. In 2017, struggling to make repayments, the government agreed to lease the port and the surrounding area to the same Chinese company for 99 years (Safi M. et al., 2018). That is not an isolated case since many low and middle-income economies already have poor medium-term outlook for debt sustainability. Investments must be consistent with national development priorities considering the vulnerabilities created by high public debt levels.

Environmental risks

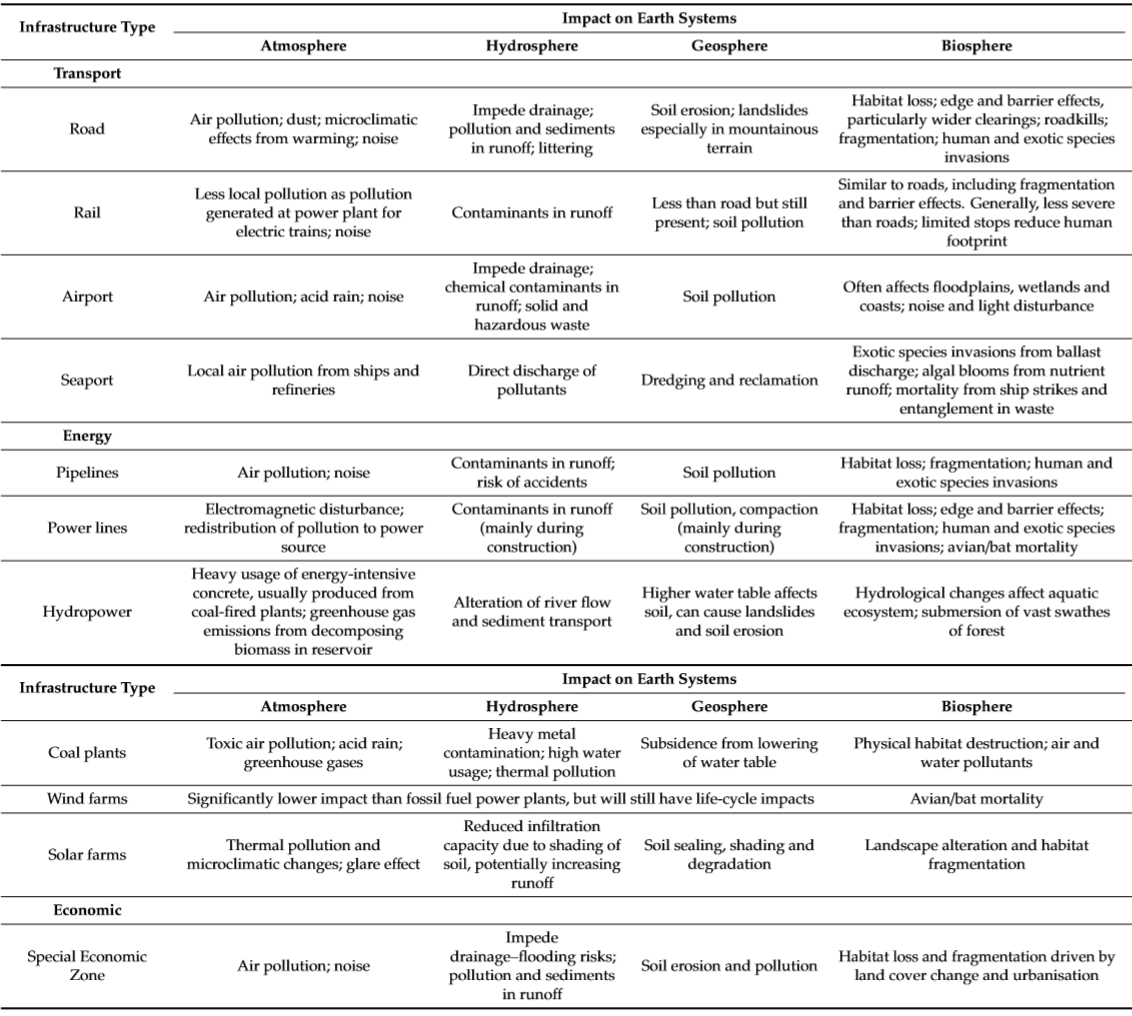

Different types of infrastructure development affect different components of the Earth systems as summarized in Table 1. Most of BRI routes pass through ecologically important and sensitive areas prone to flooding, degradation, and landslides, mostly inadequately protected. Environmental risks related to BRI infrastructure projects fall under two categories, direct and indirect (Losos E. et al., 2019).

Direct effects caused by the constructions and operations of rails and roads are localized and occur in the short-term. erosion, air and water pollution, habitat destruction and fragmentation, barriers to animal migration, illegal poaching, timber extraction, wildlife-humans incidents, and many others. For instance, it has been estimated that BRI projects will increase global carbon dioxide emissions by 0.3%, but 7% or more in low-income economies such as Lao PDR, Cambodia and Kyrgyz Republic due to the rise of sectors with high emissions (World Bank, 2019). Air pollution from industrial land and sea transports is not the only problem posed by new silk routes. In addition to energy resources, many other materials and minerals are needed to complete this project and their extraction and transport do not fail to cause significant damage to the environment.

The Chinese trade initiative risks compromising the limitation of global warming to 2°C. A study by the Tsinghua Center for Finance & Development estimates that the current carbon footprint of the Belt and Road Initiative should be reduced by 68% to stay within this limit. Otherwise, it could lead alone to a warming of nearly 3°C (Héraud B., 2019).

Indirect effects are caused by land-use responses. Once the infrastructures begin operating, markets, human populations and more generally, whole economies shift benefiting from lower transport costs. This may lead to immediate habitat loss, wildlife and timber trafficking, which are long-term economic and environmental effects with bigger impacts.

Multiple direct and indirect impacts can aggregate and interact to produce cumulative impacts occurring at multiple temporal and spatial scales along BRI routes and new or previously less accessible locations. The effects of cumulative impacts can affect different Earth systems such as the atmosphere, the biosphere, the hydrosphere and the geosphere at a local, regional, and global level (Chen Teo H. et al., 2019).

One of the major environmental risks easily evaluated through satellite data is the forest cover loss. This method is commonly used to monitor human activity impacts on biodiversity, water provision, carbon storage and other eco-services in the most vulnerable areas. To assess deforestation risks within the BRI corridors, three landscape settings have been distinguished according to their prior development and prior forest loss (Losos E. et al., 2019).

Within areas that already faced high deforestation and high prior economic development there is little natural forest cover left so that minimal forest impact is expected from transport projects. Rural transformation such as afforestation and restoration may even occur due to lower transport costs.

Areas that have experienced medium natural forest cover loss and medium prior development in the last 15 years are expected to see the greatest deforestation and eco-services losses. These forests are close to road and rail networks yet not cleared, but conditions are optimal for the expansion of economic activities. The new high-speed rail project planned in Laos is an example of these case scenario due to its heavy environmental impacts.

Low deforestation and low prior economic development areas are those that do not offer the conditions for rapid economic development so that immediate effects from BRI infrastructures may remain circumscribed. However, long-term impacts such as migration and complementary investments could represent an enormous risk resulting in forest clearing escalation.

New infrastructures connecting high prior development areas through cleared lands are those leading to smaller deforestation risks and higher economic gains. The location of new roads and rails greatly matter on the positive or negative impact of net benefits. Complementary mitigation policies can reduce project risks, costs and delays. Avoiding and reducing risks, restoring ecosystems and offsetting damages are four strategic mitigation actions that could limit environmental risks if combined and integrated into the earliest stages of the development planning for BRI’s economic corridors. These fundamental mitigation actions are more successful if they are politically advocated, supported and determined through a strategic, regional and cumulative environmental assessment.

Table 1: Main direct impacts associated with a range of infrastructure development. Source: Chen Teo H. et al., 2019.

Table 1: Main direct impacts associated with a range of infrastructure development. Source: Chen Teo H. et al., 2019.

Standards, regulations, and policies

Complementary trade policies and border improvement reforms promoting integration and inclusiveness across sectors and firms are fundamental to improve BRI benefits from transport projects, decrease restrictions, and reduce the risks of stranded infrastructures. For instance, reducing border-crossing times and delays would allow firms to import essential goods for production, thus increasing efficiency and exports. Improving the regulatory environment and legal protection of investments would increase private sector participation, this reducing fiscal risks and ensuring of BRI projects.

China has pledged that all projects will be conformed to the host-country legislation. Yet policies, governance willingness and capacity to ensure environmental protection vary greatly along the corridors and are often inadequate to mitigate greenhouse-gas emissions, alteration of habitats, loss of biodiversity etc… China itself has enhanced its domestic environmental protections and regulations. For instance, NGOs and industry associations proposed a series of guidelines and regulations representing environmental and social mitigation commitment for responsible transportation infrastructure investments for foreign outbound investments by Chinese firms. However, there is no evidence of implementation, monitoring and enforcement of these practices. Moreover, the choice whether to follow these suggestions or not is voluntary.

Particular attention has been given to China’s involvement in coal power plant projects. In fact, China participated in 240 such projects in 25 BRI countries by the end of 2016, even though most of them were launched before 2013, when the BRI was undertaken (Chao Z., 2018). Developed countries pledged on limiting the use of coal and boosting the expansion of clean energy, but coal power plants remain the cheapest means of meeting the surging energy needs.

A process for predicting and assessing the potential environmental and social impacts of a proposed project, evaluating alternatives and designing appropriate mitigation, management and monitoring measures should be included as a common mechanism. The preparation of an Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) must to be early undertaken in the project cycle, both from China and host countries. The guidelines have been prepared to reflect international good practice and offer a practical guide for all projects, both large and small scale, for practitioners and project decision-makers. The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and Silk Road Fund are the two institutions that have been established to financially support BRI infrastructure constructions. Investments should be in line with their commitments to backing the fight against global warming. When social and environmental impacts of a project are too important, international banks should use ESIA guidelines as a major tool to foresee restoration of degraded environments or revoke the funds to impede its realization.

In so doing, it is possible to enhance the degree of flexibility to locate new transportation infrastructures where the minimum environmental and social harm is generated while keeping connectivity and economic benefits. BRI corridors are large enough for evaluating indirect environmental risks and adopt the full range of mitigation options. ESIA procedures would be even more efficient if carried out by institutions representing all affected sectors in China and host countries.

Summary and conclusion

Given the magnitude of the projects involved under the Belt and Road Initiative, potential economic, social and environmental impact are extensive. BRI investments have the great potential to boost trade, foreign investments and integration of markets for those countries adhering to the Chinese project, with the condition of seriously implement a series of regulations and policy reforms while promoting the concept of ecological civilization. First, strategic coordination between countries implementation plans of sustainable development should be enhanced without violating the main principles of the BRI including inclusiveness, coordination, consistency and capacity-building. Secondly, countries are encouraged to achieve the “Five Goals” embedded into the concept of green development, namely policy coordination, facilities connectivity, unimpeded trade, financial integration, and people-to-people bond while reducing the adverse effect to ecological environment during the implementation of the initiative (CCICED, 2018).

Chinese government stated in more occasions its commitment to a greener and more sustainable BRI to make it environment-friendly. Chinese President Xi Jinping, in his speech at the Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation in May 2017 said “we should pursue the new vision of green development and a way of life and work that is green, low-carbon, circular and sustainable. Efforts should be made to strengthen cooperation in ecological and environmental protection and promote ecological civilization so as to realize the goals set by the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development” (CCICED, 2018). Although there is no evidence of standards and regulations implementation at national and international levels. Furthermore, more intense, frequent and faster exchanges will be more polluting.

Small compensations for the environment have minor impact when compared to the environmental degradations that will further occur. The legitimacy of the program cannot be taken for granted, especially by those countries that are strictly involved to the initiative. The inability of corridor countries in promoting ecological and environmental protection and the complexity of international cooperation projects bring a series of challenges to greening the Belt and Road. To limit the drawbacks of such an immense plan, strategic planning at an early stage of the project, transparency and complementary environmental assessment procedures are fundamental to tackle socio-environmental risks while pursuing economic gains.

The BRI will further contribute to global climate change and China is well aware that a climate-unfriendly BRI is not affordable as of now. To this end, China still has a lot to do.

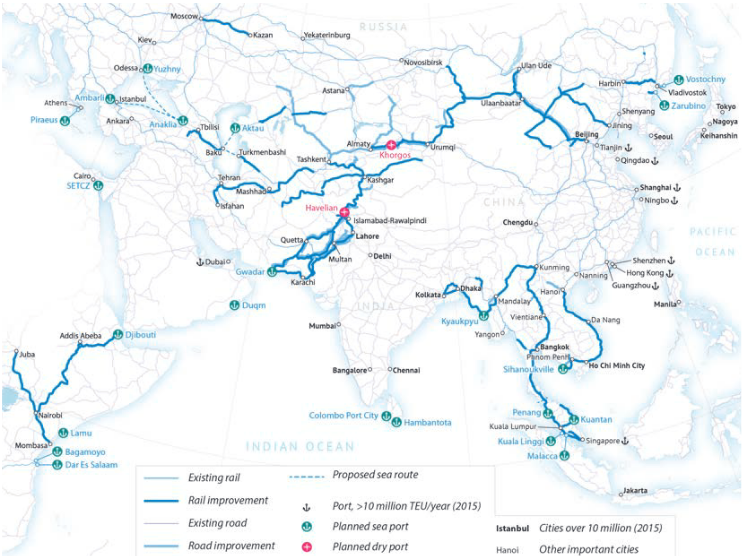

Figure 2: Magnitude and type of BRI infrastructures.

Figure 2: Magnitude and type of BRI infrastructures.

Source: World Bank, 2019.

–

References

Bradsher K., 2018. “China Taps the Brakes on Its Global Push for Influence”. The New York Times. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/29/business/china-belt-and-road-slows.html.

CCICED. 2018. “Special Policy Study on Green Belt and Road and 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development”. 2018 Policy Paper for discussion, CCICED 2018-2019.

Chao Z., 2018. “The Climate Change Promise of China’s Belt and Road Initiative”. The Diplomat. Available at: https://thediplomat.com/2018/01/the-climate-change-promise-of-chinas-belt-and-road-initiative/.

Chen Teo H., Lechner A. M., Walton G. W., Ka Shun Chan F., Cheshmehzangi A., Tan-Mullins M., Kai Chan H., Sternberg T., Campos-Arceiz A., 2019. “Environmental Impacts of Infrastructure Development under the Belt and Road Initiative”. MDPI. Available at: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=2&ved=2ahUKEwjlq6bKoKflAhWlA2MBHY-gCooQFjABegQIBRAC&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.mdpi.com%2F2076-3298%2F6%2F6%2F72%2Fpdf&usg=AOvVaw1peAJm_YPD4opQ4gZIjpcV.

Gokkon B., 2018. “Environmentalists Are Raising Concerns Over China’s Belt and Road Initiative”. Pacific Standard. Available at: https://psmag.com/environment/environmental-concerns-over-chinese-infrastructure-projects.

Héraud B., 2019. “Les nouvelles routes de la soie mettent en péril l’Accord de Paris”. Novethic. Available at: https://www.novethic.fr/actualite/environnement/climat/isr-rse/la-nouvelle-route-de-la-soie-pourrait-mettre-en-peril-l-accord-de-paris-147649.html.

Hillman J., 2018. “How Big Is China’s Belt and Road?”. Center for Strategic and International Studies. Available at: https://www.csis.org/analysis/how-big-chinas-belt-and-road.

Phillips T, 2017. “What is China’s belt and road initiative?”. The Economist. Available at: https://www.economist.com/the-economist-explains/2017/05/14/what-is-chinas-belt-and-road initiative.

Li N., Shvarts E., 2017. “The Belt and Road Initiative – WWF Recommendations and Spatial Analysis”. WWF. Available at: http://awsassets.panda.org/downloads/the_belt_and_road_initiative___wwf_recommendations_and_spatial_analysis___may_2017.pdf.

Losos E., Pfaff A., Olander L., Mason S., Morgan S., 2019. “Reducing Environmental Risks from Belt and Road Initiative Investments in Transportation Infrastructure.” Policy Research Working Paper 8718, World Bank, Washington, DC.

Phillips T., 2017. “The $900bn question: what is the Belt and Road initiative?”. The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/may/12/the-900bn-question-what-is-the-belt-and-road-initiative.

Ruta M., 2018. “Three Opportunities and Three Risks of the Belt and Road Initiative”. World Bank. Available at: https://blogs.worldbank.org/trade/three-opportunities-and-three-risks-belt-and-road-initiative.

Safi M., Perera A., 2018. “‘The biggest game changer in 100 years’: Chinese money gushes into Sri Lanka”. The Guardian. Availble at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/mar/26/the-biggest-game-changer-in-100-years-chinese-money-gushes-into-sri-lanka.

World Bank. 2019. “Belt and Road Economics: Opportunities and Risks of Transport Corridors” Advance Edition. Report Number 137911, World Bank, Washington, DC.