Juliette Landry (EnvIM 2018)

A pathway towards a transformative and inclusive global framework

One million species threatened, 75% of lands and 66% of marine ecosystems damaged, for the most part by… humans. The newly released global assessment on biodiversity and ecosystems demonstrated a terrifying reality and an uncertain future. Could multilaterism make a difference and create incentives?

The silent crisis

International negotiations represent an excellent opportunity to spotlight environmental issues. In 2015, the 21st Conference of Parties (COP) of the United Nations Framework for Climate Change (UNFCCC), that led to the Paris Agreement, highlighted and mediatized the issue of climate change. Since then, climate change has increasingly become one of the greatest concerns worldwide. Different tools have also been implemented in order to mitigate and adapt to climate change. Several stakeholders have long not even waited for governments to take actions: NGOs, foundations, companies and other non-state actors are now more and more influent in the process.

Despite some drawbacks, like the United States’ withdrawal threatening multilateralism or the last IPCC report asking for more ambitious commitments when reviewing the current ones, the Paris Agreement is recognized as a success on multiple aspects. After having raised awareness on the matter, more and more individuals are now changing their way of life in order to mitigate impacts. The most frequently known impacts of global warming are rising seas, more recurrent extreme weather events and intense heat waves, or droughts menacing food production. However, climate change impacts on biodiversity and ecosystem services are often relatively unknown and underestimated by the general public.

Biodiversity, Ecosystems & Climate Change: the current lose-lose situation

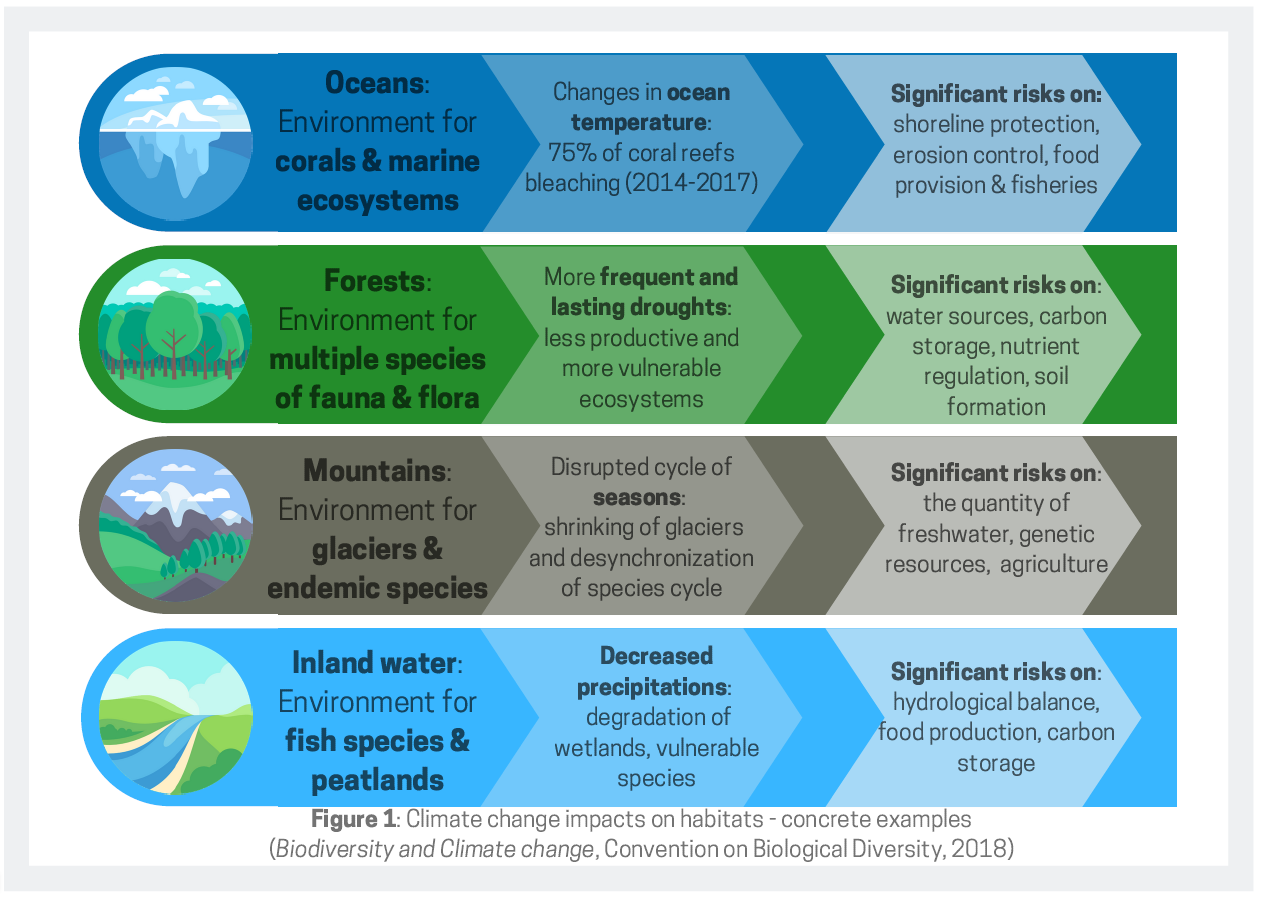

Yet, those two issues are fundamentally linked one to the other. First and foremost, biodiversity and ecosystems are strongly affected by climate change. In 2005, the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA), which aimed at assessing human impact on ecosystems, alerted on the fact that climate change was about to become the predominant cause of biodiversity loss. And there are nowadays some concrete and tangible examples. Climate change is subsequently modifying different types of environments and ecosystems (e.g. forests, oceans, mountains, inland water, see Figure 1) in which a considerable number of species are not able to adapt or adapt their habitat fast enough. Some other species simply cannot move to another adequate environment.

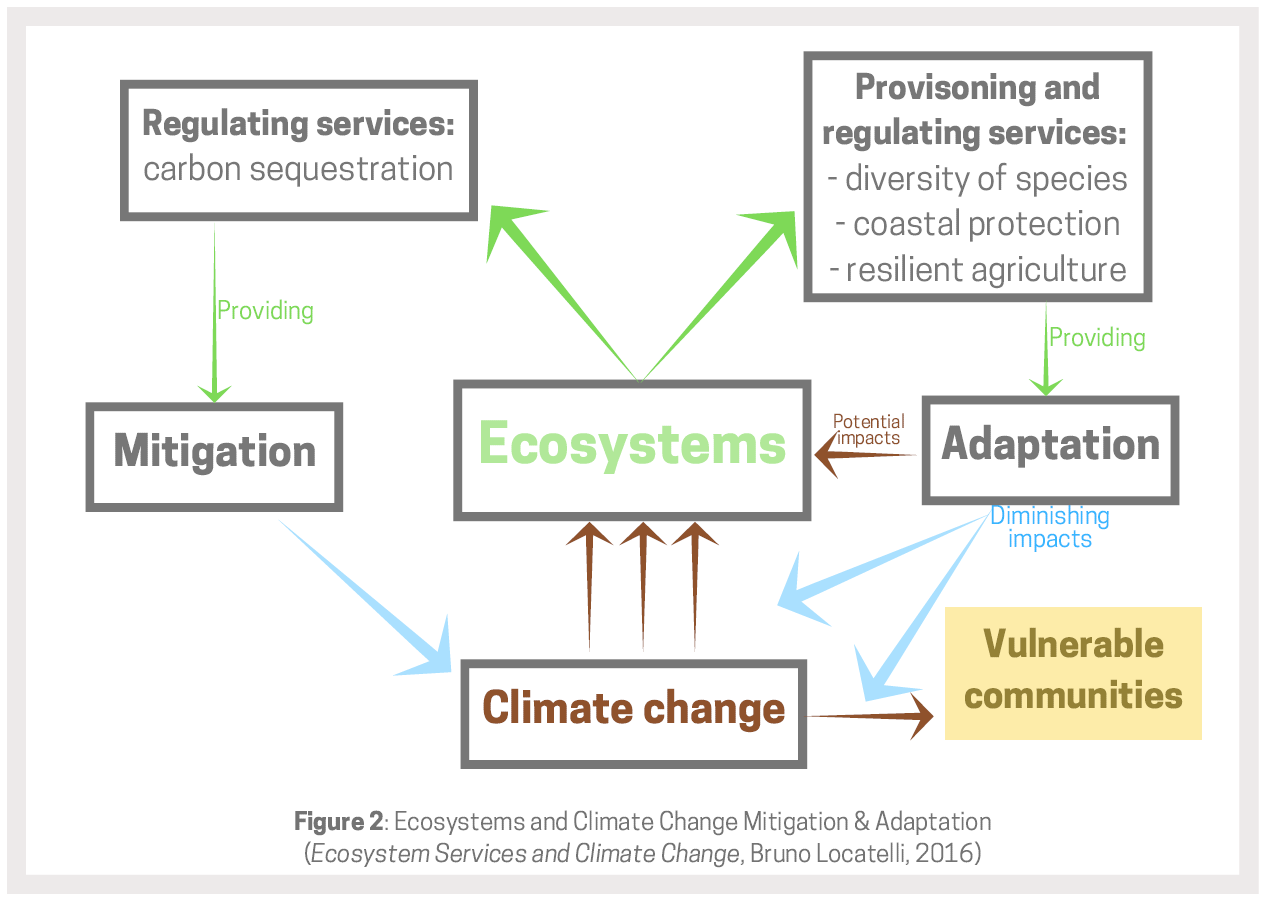

But there is another side to this issue. Biodiversity and ecosystems loss also have direct impacts on climate change and contribute to its acceleration. Healthy ecosystems indeed contribute to mitigating climate change mainly through their capacity to remove carbon from the atmosphere and to store it. Oceans stored up to 48% of carbon emitted by humans since the beginning of the industrial area (Monaco & Prouzet, 2014), and their capacity to store it strongly depends on their temperature (the warmer they get, the less they can actually store). In 2018, a study showed that 450 billion tons of carbon are stored in trees and vegetation (Erb et al. 2018). But peatlands represent the largest terrestrial natural carbon store, with 0,37 gigatons of carbon being sequestered each year (IUCN, 2017). Ecosystems in general have a significant role in order to adapt to climate change and its associated consequences (e.g. sea-level rise, extreme weather events).

When damaged, through for instance ocean’s temperature warming, desertification, land degradation or droughts, those natural solutions to the climate change issue actually become one of the reasons accounting for the acceleration of global warming (carbon released) and having more significant impacts (destruction of protecting ecosystems). There is then an increasing need to assess and pursue those two challenges -biodiversity loss and climate change- jointly (Figure 2).

Biodiversity at the core of our survival

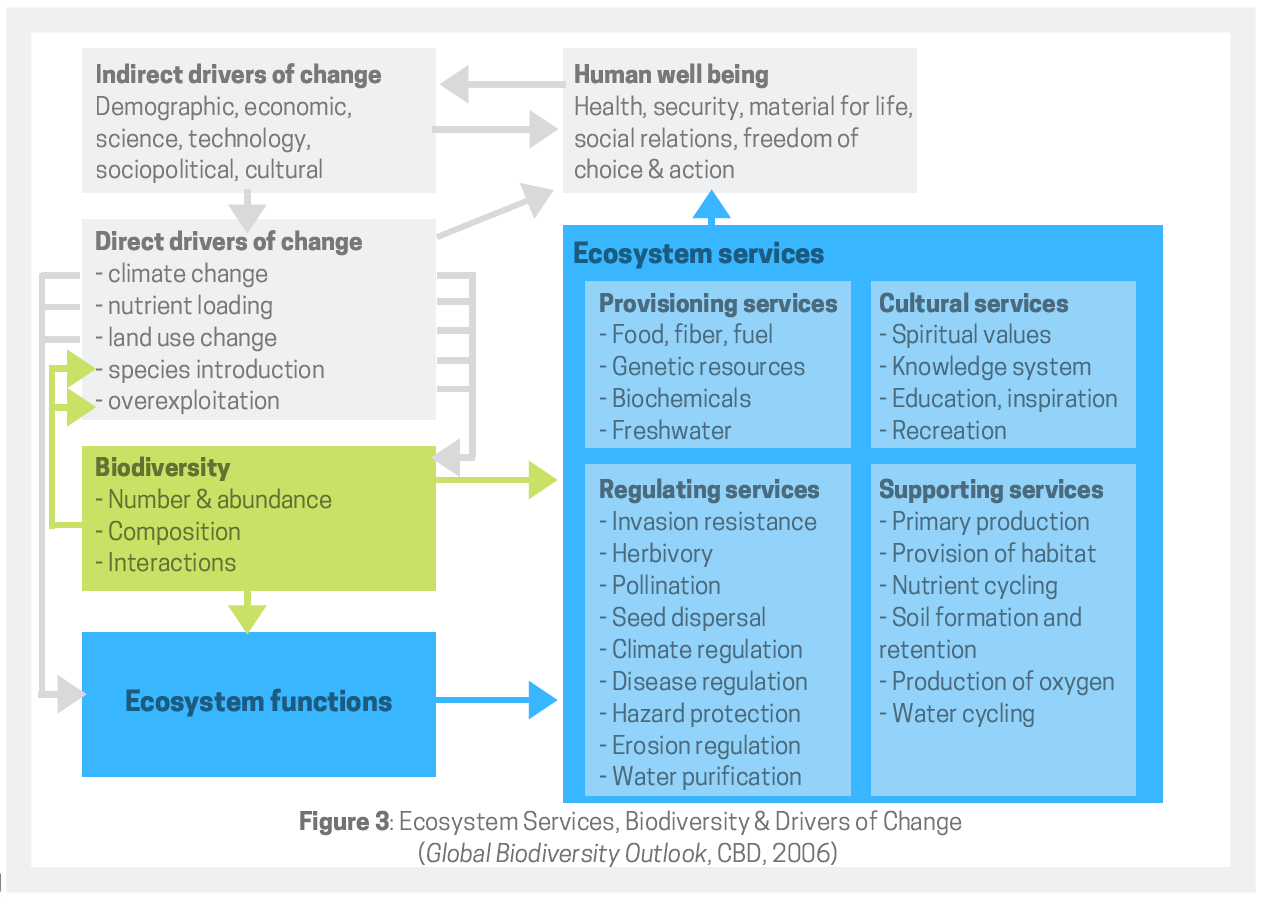

But what are biodiversity and ecosystems exactly? Why are they related and so important to human well-being in a more general way? Biodiversity, that is to say, biological diversity is a relatively young notion that emerged in the 1980s. According to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), biodiversity means the “variability among living organisms from all sources including terrestrial, marine and other aquatic ecosystems and the ecological complexes of which they are a part; this includes diversity within species, between species and of ecosystems”. Biodiversity is what we might call “the living material” of our earth, the diversity and number of species and ecosystems. As for ecosystem services, the MEA defines those as “benefits people obtain from ecosystems” and are strongly related to biodiversity. However, when only described this way, biodiversity and ecosystem services might seem pretty far from us humans. Biodiversity is often mentioned in the media when emblematic, charismatic species are endangered (e.g. pandas, lions). Their survival is of course at stake and should be spotlighted. But is that all?

More concretely and above all, biodiversity represents everything that is living. Biodiversity is what we eat and drink (from the tomato in our pasta sauce to the grape used to make our wine). Biodiversity is what we use to get dressed (the cotton of our sweaters) and to shelter (the cement of our house). Biodiversity is also the diversity of organisms and genes that, when studied, can become a source of medications (e.g. aspirin or many treatments against cancer).

Biodiversity loss is then threatening humanity’s survival and ecosystems on a large scale. When species disappear, relations between living organisms also change and deteriorate. For instance, insects (that provide pollinating services and contribute to soil fertilization) are endangered because of pesticides but are vital to trophic chains: birds, amphibians and other species find their source of food in insects and they also play a role within the same ecosystem. Ultimately, the decreasing number of insects have impacts on the ecosystem balance. This snowball effect contributes to the decline of ecosystems that provide food production, water, oxygen among others. Those services are called “ecosystem services” (Figure 3).

Nowadays, the destruction of ecosystems is the main factor of biodiversity loss, the biodiversity that is itself maintaining healthy ecosystem functions. According to the recent IPBES report, the world is close to the beginning of the 6th mass extinction of species. Previous extinctions, of course, occurred in the past. Huge volcanic eruptions or meteorites caused severe impacts on biodiversity. However, this current mass extinction is today caused, for the first time, by a form of life: humans. Apart from climate change due to GHG emissions, sbiodiversity and ecosystems are impacted by habitat change through, among others, land-use changes, invasive species and pollution (MEA, 2005). And the results are alarming. For instance, between 1970 and 2014, the Earth has lost in average 60% of vertebrate species, which means that the number of species is decreasing at a rhythm 100 to 1,000 times higher than before human activities started to modify ecosystems (WWF, 2018). During the same period of time, the world human population has doubled.

From stopgap solutions to a sustainable response?

Even if the issue is increasingly discussed and tackled, the figures transparently show that current solutions are not sufficient. As indicated above, biodiversity and ecosystems loss is still a relatively unknown problematic compared to climate change, even if both issues are exacerbating each other. However, back in 1992, during the Earth Summit of Rio, three concerns were taken into account and brought to the discussion: climate change, biodiversity loss and desertification. Accordingly, three organizations were created via the Rio Conventions -the UNFCCC to tackle climate change, the UNCCD to combat desertification and the CBD to conserve biological diversity.

Since 1992, on a similar organizational structure as UNFCCC, the Parties of the CBD have met every two years during what is also called Conference of Parties (COP). And, as UNFCCC COPs led to climate-related agreements, the COPs of the CBD led to actions and protocols to conserve biodiversity and ecosystems. However, such as for the climate change issue, those agreements are criticized. Tangible results are minimal.

Nevertheless, international negotiations are necessary to fight environmental and transboundary problematics. Parties are needed around the table to enhance multilateral tools. Once again, international events, if well prepared, also offer visibility on the issue and should encourage individuals and non-state actors to press States to undertake significant actions.

Then, the next significant rendez-vous on biodiversity in Kunming (Yunnan, China) in 2020, for the COP15 of the CBD, is eagerly awaited by alarmed scientists, NGOs and more globally by involved and concerned people and organizations. What exactly will be at stake in China in October 2020 and, more importantly, from now to then?

Learning from failure, learning from improvement

In December 2015, negotiations started in Paris and the objective was high. The 21st COP was considered as a crucial turning point after decades of diplomatic failures to fight climate change. Many countries indeed withdrew from the Kyoto protocol and the negotiations at Copenhagen for the 15th COP, which were supposed to provide a continuation to Kyoto’s protocol, was a complete failure mainly because of conflicts between developed and developing countries. However, in 2015, the Paris Agreement was finally signed and then said to be a success. As for the biodiversity loss issue, the challenge is pretty similar for the COP15 of the CBD in Kunming, in 2020. A question is raised here: will Post-2020 agreement for biodiversity learn from Paris Agreement’s successes and weaknesses?

Insufficient previous and current commitments for biodiversity

In order to better understand future challenges, the historical timeline of CBD’s agreements and actions and their results is of course needed. The CBD was opened for signature in 1992 at the Rio Earth Summit and entered into force in 1993. It has three main objectives: the conservation of biological diversity, the sustainable use of the component of biological diversity and the equitable sharing of the benefits from the utilization of genetic resources. The treaty led to the creation of a Secretariat, based in Montreal, but also to several units, programs and working groups providing guidelines and advice for negotiations. The complex structure is composed of the SBSTTA (Subsidiary Body on Scientific, Technical and Technological Advice), meeting several times prior to each COP, and the SBI (Subsidiary Body on Implementation), which aims at reviewing and enhancing the implementation of the CBD.

More than that, the CBD was created to become an effective framework for additional actions. Three protocols, which are supplements to the CBD, were adopted to cope with further issues. The Cartagena Protocol (2000) aims to protect biodiversity from Genetically Modified Organisms (GMOs), the Nagoya Protocol (2011) aims at fairly and equitably sharing access and benefits of genetic resources and the Nagoya Kuala-Lumpur Supplementary Protocol (2011) is a supplementary protocol to the Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety.

At the same time, general targets were voted in order to reduce global threats to biodiversity and ecosystems. In 2001, the 2002-2010 Strategic Plan was implemented; one such strategic document intended to decrease the rate of biodiversity loss, through four main goals, including the integration of biodiversity concerns within national strategies. The 2010 Target also included 21 Sub-targets, such as the effective conservation of at least 10% of the world’s ecological regions. However, in 2010 (International Year of Biodiversity), the Global Biodiversity Outlook 3 (GBO-3) demonstrated that, despite the implementation of significant breakthroughs, no sub-target was achieved and indicators showed negative and increasing pressures to ecosystems.

In 2010, in Nagoya, the Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011-2020 and Aichi Biodiversity Targets updated the previous targets. The twenty ambitious conservation goals represent a framework and support for Parties to revise their National Biodiversity Strategies and Actions Plans (NBSAPs), which should be submitted according to Aichi Biodiversity Target 17. The COP15 in Kunming will be the opportunity to assess Aichi Targets and NBSAPs. However, all indications are that the outcome will not be positive. The trajectory of extreme biodiversity loss is not reversing.

The next challenge for Kunming 2020 is then to avoid replicating the same kind of agreement and targets, which are ambitious but that do not encourage responsibility and effective monitoring tools. The NBSAPs system shall be improved in order to better coordinate and report on a global scale.

A necessary structural change

This challenge is quite similar to what Paris COP21 faced in 2015 and several discussions are then questioning the idea to model from what has been decided there. Following Copenhagen, innovative solutions were designed to avoid diplomatic failures and to facilitate the adoption of a global agreement. First, in order to do so, the “top-down” approach, with a global objective shared by Parties, was combined to a “bottom-up” approach. The baseline universal long-term goal (limiting global warming to 1.5 to 2°C) was coupled with Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) to achieve it. This means that each country was requested to outline their climate actions on a voluntary basis, prior to COP21 in Paris. This innovative process diminished tensions between “historically responsible countries” and emerging, developing countries.

As the CBD failed to properly integrate economic, financial, and other non-state actors in the combat against biodiversity loss, the Paris Agreement was also the opportunity to develop a non-state Agenda that offers a platform for companies and regional organizations to submit commitments. The Global Climate Action portal today counts more nearly 20,000 actions and for instance enabled the American States and cities to compensate for the US withdrawal from the Paris Agreement.

The climate-related agreements also implemented a way to transparently disseminate and analyze countries’ commitments and results. The Article 13 of the Paris Agreement launched a new type of Monitoring, Reporting and Verification (MRV) system that is necessary for the UNFCCC’s actions and agreements. The so-called “Enhanced Transparency framework” (ETF) is made to build mutual trust, legitimacy at the international scale but is also made to constantly upgrade ambitions and voluntary commitments (NDCs). Another tool, which is the Talanoa Dialogue, aims at improving national targets to keep global warming below 2°C but also prepare a global stocktake and a ratcheting up process. Launched in early 2018, its objective was to review the progress of climate action since Paris Agreement and to raise climate efforts through exchanges on lessons learnt and feasible options. This dialogue was the opportunity to encourage solutions and discussions. At its closure at COP24 in Poland, only a few countries however show the intention to reconsider their commitments before 2020 and the finale decision does not obviously request more ambitious ones.

But this whole procedure put into practice for the climate change issue represents a good basis for the post-2020 global biodiversity framework. The current CBD process is limited and showed ambitious targets with insufficient implementation, monitoring, supplementary tools. A few ideas gleaned from the preparation of the Paris Agreement and are now identified. First, NBSAPs could be used at the same format as NDCs for climate action and could be prepared prior to the COP15. Another option could be the creation of commitments, linked to NBSAPs. Those should be articulated, reported, verified in accordance with global targets in order to properly meet the biodiversity loss challenge. Those national commitments could also be supported by non-state commitments, which would also be monitored and reviewed by dedicated technical experts groups. Information shared at the national or regional level could then be analyzed by independent bodies at the international level. Dialogues and platforms could also be opened and could enable better coordination of commitments and capacity-building towards developing countries. All of these procedures would finally offer visibility to the international transboundary challenge of biodiversity loss. In a word, an innovative structure is more than required for the CBD, while taking previous failures into account.

The complexity of biodiversity indicators

A system to monitor, report and verify commitments on biodiversity would be necessary to track what has been done, what still need to be done, and would create synergy through lessons learnt and capacity-building. But while climate change mitigation is relatively easy to measure, through the single unit of CO2, commitments to address biodiversity loss would not be efficient if only aiming at using one unique indicator. Indicators used have to go further than a simple number of species declared extinct and a global target. A suite of indicators, including pressure, state and response indicators, and closely linked to targets to be determined, have to be prepared accordingly.

Nevertheless, the 2°C global indicator for climate change has shown benefits on awareness and communication aspects. A global single indicator for biodiversity could reach a broader public and mainstream the issue. And it still could be combined with more precise biodiversity indicators when it comes to measuring and verifying national commitments.

Conciliating climate change and biodiversity loss issues (among others)

What is also required when addressing environmental issues is a strong collaboration between connected challenges. As discussed in the first part of this article, biodiversity loss and global climate change are aggravating each other. More, desertification is also a strong driver of both issues. When addressing one of these three issues independently, some actions and projects -for instance, adaptation to climate change- can have significant negative impacts on the others. A partitioning system has to be avoided. Agendas, agreements and dialogues should be coordinated between the UNFCCC, the CBD and the UNCCD to prevent counterproductive responses, on one hand, and, on the other hand, to enhance coherent and integrated efforts. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), created in 2015 under the UN framework, should be used in this perspective.

In addition, the CBD emphasizes the necessity to enhance sustainable development, that is to say, the combination of political, economic, social and environmental objectives to create prosper societies. The protection of biodiversity and ecosystems indeed requests the integration of all sectors, industries through a collective response. The preparation of the 2020 meeting in Kunming represents a good opportunity to underline this scheme.

The bulk of the work now begins

As for Paris Agreement voted more than 3 years ago, the new agreement on biodiversity conservation must be prepared and thought prior to the COP15 in Kunming. Some parameters need to be considered and developed such as the legal status of the agreement, the research basis for negotiations and the future national commitments and indicators that will be used within the post-2020 framework.

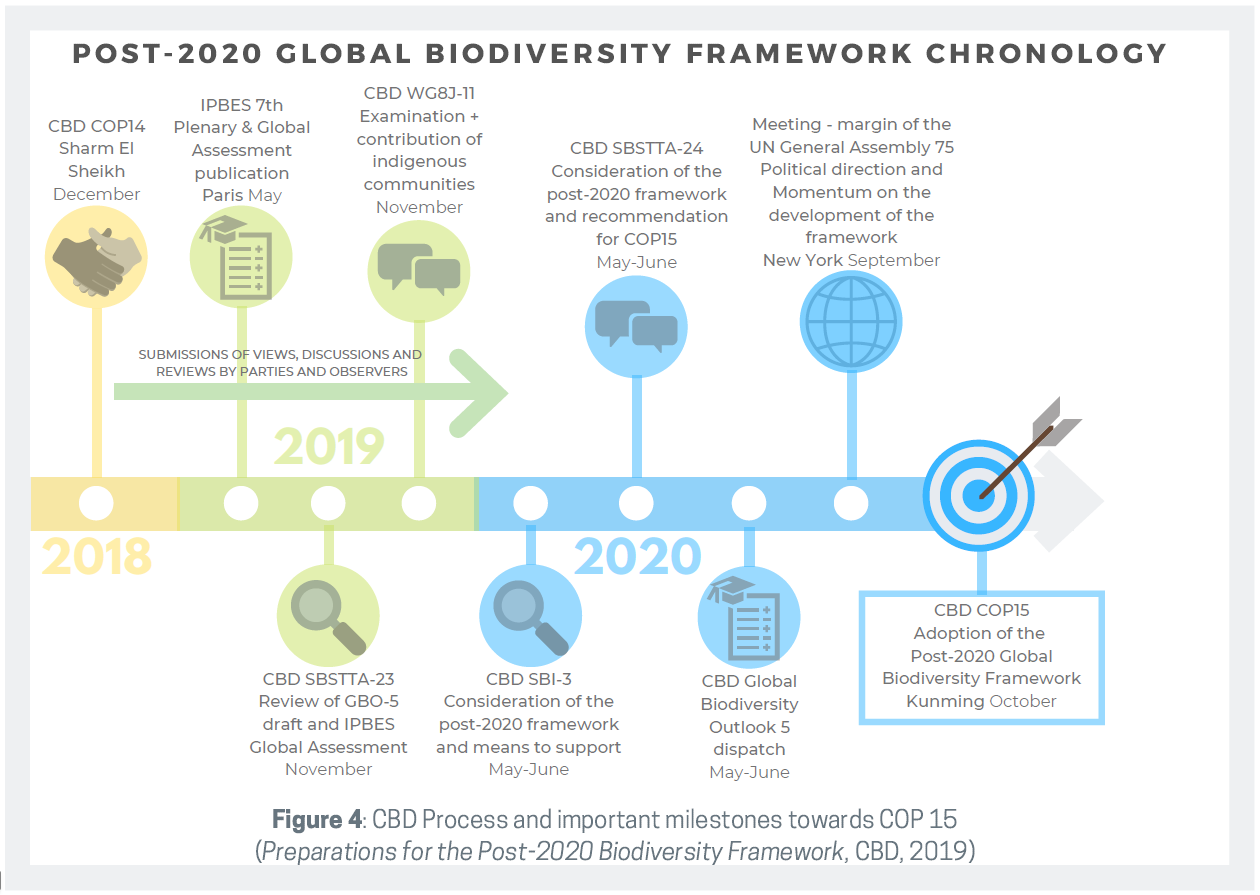

The COP14, held in Sharm El-Sheikh in Egypt, last November, aimed at preparing the next two years and at providing precise steps to develop the post-2020 framework to be signed in Kunming. An indicative chronology of key activities and milestones has emerged from discussions, following SBI recommendations and Parties and stakeholders insights. Dedicated subsidiary bodies will for instance review propositions and drafts before Kunming 2020. Other additional mechanisms such as those used by UNFCCC were also discussed, for example, to improve exchanges between governments and non-state actors. Concerning the scientific basis for negotiations, the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) 7th Plenary, was held in Paris early May and delivered a global synthesis on the state of ecosystems and potential scenarios that hopefully will be considered to tackle the issue.

However, the schedule is tight compared to the timeline that led to the Paris Agreement on climate (Figure 4). Two years might be insufficient to mobilize so many stakeholders. Strong mandates for Parties delegations have to be adopted, Parties should coordinate at the sub-regional and regional level, key non-state stakeholders (cities, private sector, industries, youth) should be mobilized and awareness should be raised among citizens, in order to strengthen those mandates.And the countdown has already begun.

China’s expected leading role

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) is, of course, to play a significant role as the official host of the 15th COP in 2020. However, its role goes beyond the simple logistical organization of the event. China has previously represented an important player at the climate negotiating table and is becoming a significant leader in the environmental industry. The “State-party” has considered both internal and international concerns and shifted to the development of a new supposedly green model.

The federating polluter

Surprisingly, although the People’s Republic of China is today the country that is the most polluting, it has gradually integrated sustainable development goals in both national and international decisions, after decades of defiance. The Chinese economic force, following a spectacular rocketing growth, has to face serious obstacles. Firstly, economic growth is now not as high as it used to be at the beginning of the century. Secondly, the quick development of industries created serious environmental and ecological damages on both nature and people. The Chinese population, of which a large part is becoming more and more educated and richer, is frequently protesting against pollution. Xi Jinping, president of the RPC since 2012, has well understood the awakening of civil society. He then went further than his predecessor, Hu Jintao, and emphasized reforms on environmental measures within the 13th Five-Year-Plan, in 2015. He also defended his ideas of the “Chinese dream” (中国梦, Zhōngguó mèng), a “Beautiful China” (美丽中国, měilì zhōngguó) and the “Ecological Civilization” (生态文明, shēngtài wénmíng). These reforms not only aims at satisfying the Chinese population but also has to provide to the PRC new means to become a leader at the international level.

Prior to the 21st COP on climate change, China began to advocate for “differentiated responsibilities” between the “North” and the “South” and was considered as the influent representative for developing and poor countries. This debate led to tensions with developed countries, for instance, the USA, which considered that commitments from developing and, still, polluting countries were not ambitious enough (Maréchal, 2013). The situation was said to be unequal and the diplomatic failure in Copenhagen mainly occurred because of this disagreement.

In 2015, Xi Jinping reiterated the concept of “differentiated responsibilities”. Besides, the country still refused interference and systematic controls, seeking total sovereignty and reminding the importance of economic development for “Southern” countries. This is important to reckon that China has a particular role within this North-South confrontation. The PRC acts as the big brother (大哥, dà gē) of emerging and developing countries, continuing the defense of the Non-Aligned Movement, at the time of the Cold War. Being an alternative to Western countries is specific to Chinese foreign policy (Cabestan, 2015).

But, on the other hand, China advocates for treaties and agreements on environmental protection and is relatively voluntary. China, as the political leader of the “South”, of the G77 indirectly influenced more than 80% of the world population during negotiations at the COP21. On the same page, China is an important stakeholder for Western countries, particularly because of its strong economic weight. The China-USA couple was also especially crucial back then, as Xi Jinping and Barack Obama coordinated their pledge and ratification of the treaty. However, Trump is pretty isolated today as the USA is one of the two countries that are not Parties to the CBD (with the Vatican), and because of its skepticism on environmental protection.

In 2020, China will this time host the next important international forum on biodiversity conservation. Its role will be decisive in the success of negotiations and require the PRC to be proactive through political initiatives, such as France did in 2015. Secondly, China has to be a strong driver for the preparation of the agreement to be signed, that is to say, to start working now with international stakeholders, enhancing synergies among different groups of countries, involving non-state actors through an effective platform, and of course, showing and sharing best practices. In a word, China should help providing momentum.

Will China show the path?

2020 also represents a decisive year for China. It is the close-out year of the 13th Five-Year Plan, of the “Xiaokang society” policy (小康社会, Xiǎokāng Shèhuì), initiated by Deng Xiaoping in 1979, in order to create a prosperous middle-class. As a result, the concept of “Ecological Civilization” has to be ready by then. Biodiversity then logically comes under the scope of application of the construction of the Ecological Civilization and this major international event brings strength to this objective. However, to this day, China has been relatively passive on the biodiversity theme.

Nevertheless, 2020 would probably turn the tide. The PRC would reap important benefits from the organization of the COP15 of the CBD. China should enhance its fundamental role within environmental negotiations and become a strong diplomatic and international player. Organizing this type of events have constituted advantages to previous hosts: the capacity to choose the agenda, to get an important position within the negotiation process and to see long-term benefits on the international stage, also in order to protect national interests (which is the main objective for China).

In order to achieve success, the PRC has to reinforce the design of the agreement and to reverse the current passive trend. All the ministries and commissions should be mobilized, as well as Chinese industries and scientific research. The multilateral frameworks should also be fully used (e.g. the United Nations, regional organizations).

However, China must not allow to drift off the main goal, which is an effective, ambitious and results-oriented agreement on the conservation of biodiversity and ecosystems. Another way of reinforcing the success of negotiations is to raise adequate questions related to biodiversity conservation and to spotlight best practices. But what is China doing concretely to decrease human activities’ threat to ecosystems? Is the PRC remarkable?

Recently, the implementation of the “Ecological Civilization” was combined with some contradictory policies and actions. Some scandals emerged such as the resumption of the commercial ivory and tiger bones trade, along with supposed legal constraints. The trade has since then been finally forbidden. But the biodiversity loss issue is considerable in China, with the amount of endemic species and living organisms decreasing every year. The Chinese rapid industrial and demographic expansion, the introduction of alien species and climate change, exacerbated by the industrialization of China itself, led to the loss of species and key ecosystems. The government however started creating protected areas in 1990. Other progresses have been made since then, such as the establishment of monitoring systems. Conservation and communication on the issue have also been enhanced. But even if natural reserves are established, other areas are significantly and increasingly damaged by land-use changes, urbanization and related impacts, or pollution. The fight against biodiversity and ecosystems loss in China could indeed slow down the economic and industrial development of the country. Such as anywhere, internal considerations are rarely in symbiosis and this issue demands an in-depth reorganization of the economy and society. Meanwhile, according to WWF, even if protected areas helped bird populations to increase since 2000, half of vertebrates have disappeared in China since 1970.

Uniting forces for biodiversity: the only successful emergency landing

2020 will represent the year of the metal rat in the Chinese astrology. It is quite fortunate because the rat is supposed to be at the forefront of the action, attached to detail and particularly active. And the agreement to be signed in Kunming needs to be carefully prepared and also asks for a proactive and federating China. However, China is not the only stakeholder that will be watched. All state and non-state actors should be mobilized and their biodiversity-related issues understood, especially developing countries that are suffering the most from biodiversity loss. Research is also necessary to assess impacts and measures are needed. More globally, the most important objective to achieve is to find a consensus between all stakeholders, whatever they may be, governmental, individual, industrial or economic.

References:

GIZ, Deciphering MRV, accounting and transparency for the post-Paris era, Bonn, 2018

Laurans et al., ‘2018-2020 : le moment du sursaut pour la biodiversité?’, IDDRI, 2018

PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency, From Paris to Beijing. Insights gained from the UNFCCC Paris Agreement for the post-2020 global biodiversity framework, The Hague, 2018

OECD, Summary Record OECD International Expert Workshop: The Post-2020 Biodiversity Framework: Targets, indicators and measurability implications at global and national level, Paris, 26 February 2019

Wemaëre, et al., ‘Les options juridiques pour l’accord international sur la biodiversité en 2020 : une première exploration’; Décryptage, n°05/18, Iddri, 2018

Zou, et a., 中国与COP15——负责任环境大国的路径选择, 环境保护部环境保护对外合作中心, 北京, 2017